King of Diamonds, from Harlequin Cards, 2nd Series (N220) issued by Kinney Bros. 1889

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 3/4 × 1 1/2 in. (7 × 3.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

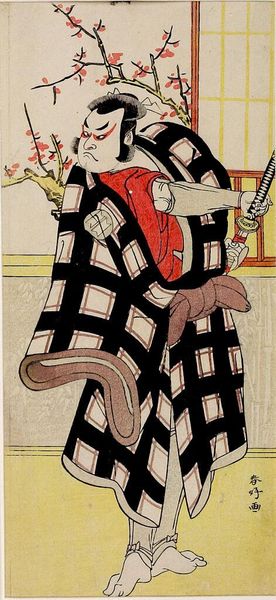

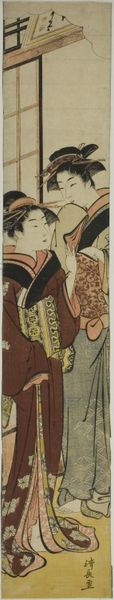

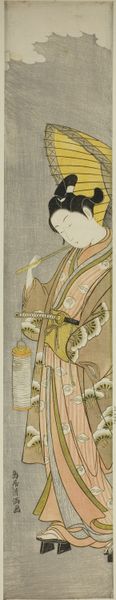

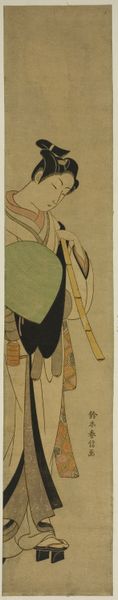

Curator: Welcome! Today, we'll be discussing a distinctive piece from 1889: “King of Diamonds, from Harlequin Cards, 2nd Series (N220) issued by Kinney Bros.” currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It's a commercial print, a rather curious specimen of the time. What strikes you most at first glance? Editor: There is a sense of immediate irony in this piece. It feels satirical. The king's posture and the imagery of scales hanging near the pot marked with a dollar sign imply a sharp commentary on wealth and power dynamics. Curator: Indeed! The caricature employs a bold color palette—salmon, ochre, and teal—typical of Art Nouveau, giving a distinct graphic quality to the work. Notice how the lines, even in the King's garments and crown, are deliberately stylized, enhancing the flat, decorative appeal inherent in the Ukiyo-e style this seems to evoke. Editor: Exactly! The cartoonish depiction invites us to question the role of this 'king' figure in late 19th-century society. It suggests themes of financial control but is it aimed at admiration or ridicule? The scale also looks unbalanced, drawing attention to a potentially inequitable system. Was the artist perhaps signaling anxieties about early capitalist structures? Curator: Intriguing, certainly. While social critique is plausible, one might also focus on how the composition, with its deliberate flatness and caricature, transforms familiar imagery into a commodity. Consider its purpose as part of a tobacco card series. Its value is perhaps less in its message, and more about the signifiers of consumer culture emerging during the Gilded Age. Editor: Still, the conscious use of caricature, a known tool for dissent, prompts further scrutiny. The "Bank" label next to the king suggests he's not merely a neutral symbol of monarchy, but of institutional power linked to financial dealings, right? To whom were these tobacco cards marketed, and what kind of engagement might a working-class consumer have had with this figure of financial power? Curator: Your reading adds layers of political intention. Though my perspective leans toward understanding it within the framework of commercial art and stylistic choices, you draw a valid connection to social issues. Editor: Ultimately, I find this work interesting for what it does: it invites one to question power and visual language during a period marked by enormous economic change. Curator: For me, its real power comes from its masterful merging of aesthetics and consumerism—a potent demonstration of form meeting function in late 19th-century design.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.