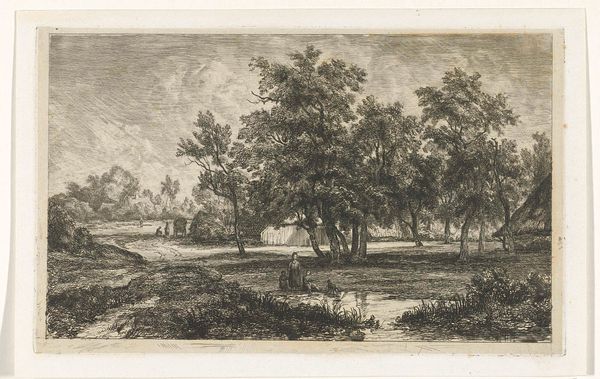

Dimensions: height 78 mm, width 123 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Landschap met twee figuren," or "Landscape with Two Figures," an etching and engraving printed sometime between 1837 and 1865. It looks like such a simple scene, but the longer I look, the more the rough, almost frantic etching style draws me in. How does its materiality inform its meaning for you? Curator: Considering this work, I'm drawn to the implications of printmaking in the 19th century. Etchings like this made landscapes accessible, consumable. How does the mass production influence our relationship to nature? It’s no longer a unique, sublime experience, but a replicated image, readily available. Look closely at how the artist uses line. Do you see how varied and textural they are, some light and airy, others densely packed to create depth and shadow? Editor: Yes, there's a real contrast. What I see now, is the artist didn't just replicate reality; the very *process* embodies a particular way of *consuming* that reality. The level of detail they achieved using simple techniques highlights how labor transforms observation into a commodity. Curator: Precisely. This landscape isn't just scenery, it’s a product, reflecting specific labor practices, skills, and access to materials of the time. Also consider its affordability, think about its implications on the class that may engage it. How did this change peoples appreciation and demand of "realistic" artwork? Editor: I hadn't thought of it like that before. It makes me wonder about the role of art schools teaching these methods to increase accessibility and artistic expression for people beyond the upper classes. I suppose that would then fuel consumption by the rising middle class. Curator: It is a constant dialogue. And in seeing art in this light, perhaps, we also become more aware of our own acts of consumption, in understanding that images always have materiality and history. Editor: Exactly. I am left reflecting about the social and political undertones of realism as more than mere observation, but engagement. Thank you for revealing this way to look at this.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.