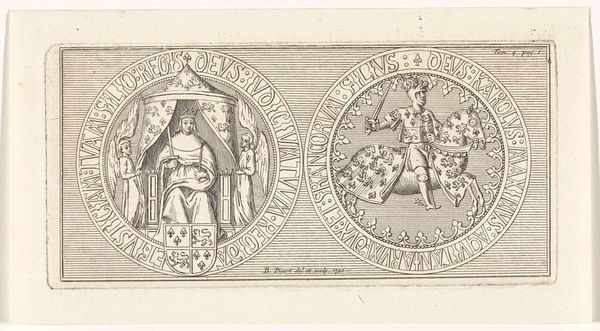

Penning met de portretten van Filips VI van Valois en Blanche van Navarra 1718

0:00

0:00

bernardpicart

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, pen, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

comic strip sketch

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

#

mechanical pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 70 mm, width 136 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Penning met de portretten van Filips VI van Valois en Blanche van Navarra" a pen drawing and engraving made in 1718 by Bernard Picart, housed in the Rijksmuseum. The stiff formality of these portrait medallions feels very…official. I’m curious, what do you see in this piece, thinking about its role in the public sphere at the time? Curator: This engraving is fascinating as an example of how history is constructed and consumed. Picart's image, based on an earlier medallion, presents us with idealized, sanitized versions of these historical figures. The very act of reproducing a medallion – originally a symbol of power and prestige – through a print medium makes it accessible to a wider audience. But it also filters and reinforces a specific, arguably propagandistic, view of royalty. Who do you think this print was for, and how would its reception differ across social classes? Editor: Well, considering its relative inexpensiveness compared to a gold medallion, a print like this could reach the bourgeoisie, solidifying their image of royalty and perhaps influencing their political views. It’s interesting how a single image can serve such different purposes depending on who's viewing it. Curator: Exactly. The distribution of such images played a vital role in shaping public perception and legitimizing power. By carefully controlling and disseminating imagery, those in power could subtly influence social attitudes and political discourse. The image of authority, skillfully crafted, becomes a powerful tool in itself. Has examining this print shifted your perception of historical portraiture at all? Editor: Definitely. I’m starting to see portraits less as simple representations of people and more as carefully constructed statements about power and social order. Thanks! Curator: My pleasure. Recognizing the power dynamics inherent in image-making is crucial for understanding both historical and contemporary visual culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.