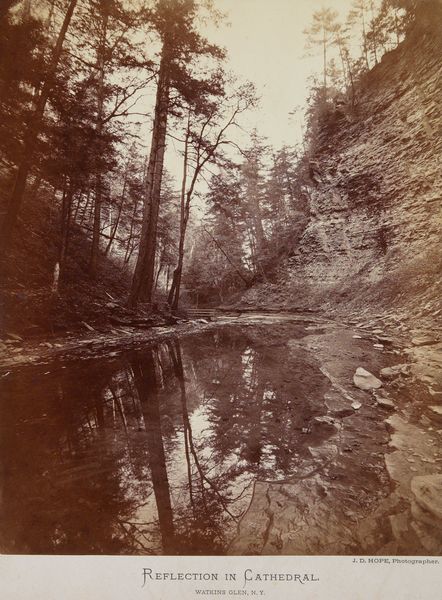

photography, albumen-print

#

natural shape and form

#

landscape

#

nature

#

photography

#

outdoor scenery

#

hudson-river-school

#

albumen-print

#

realism

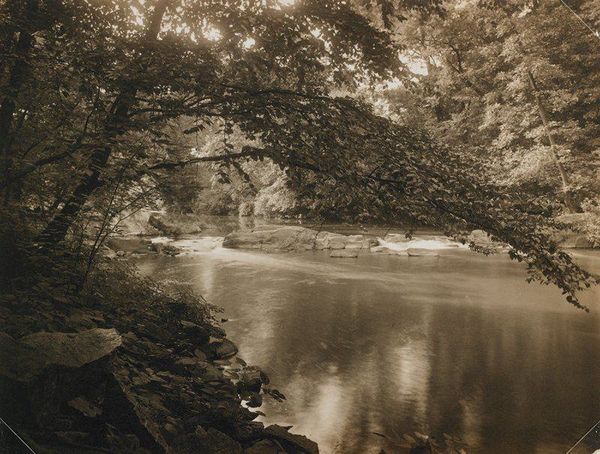

Dimensions: image: 26.3 × 33 cm (10 3/8 × 13 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

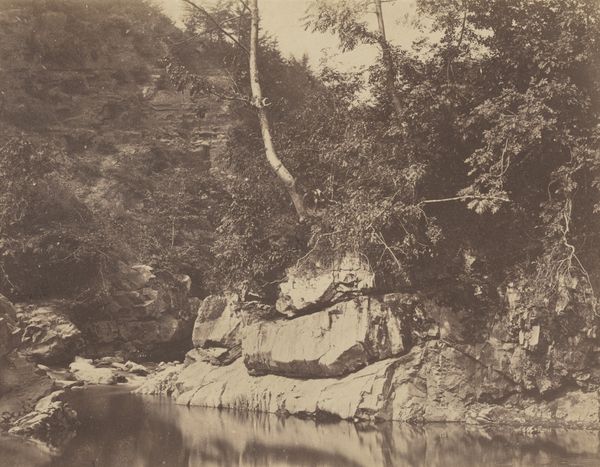

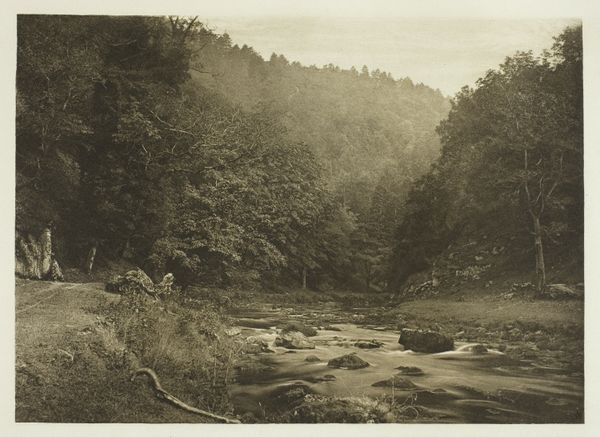

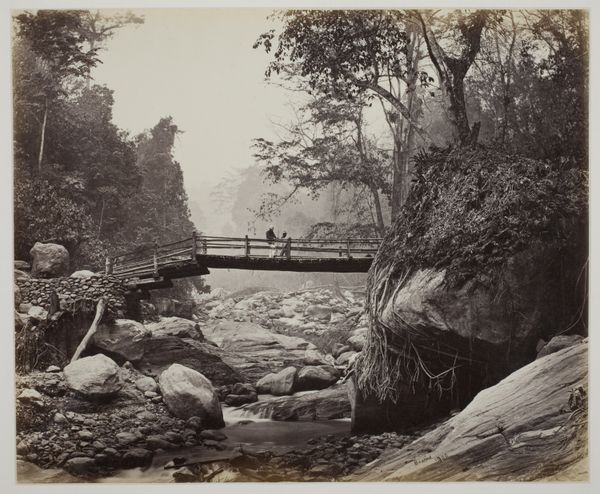

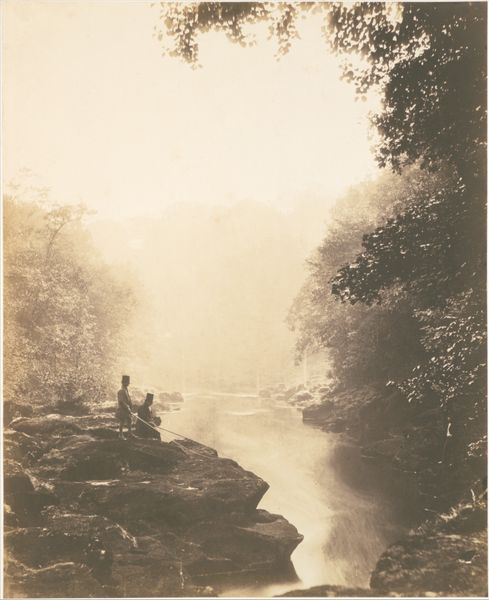

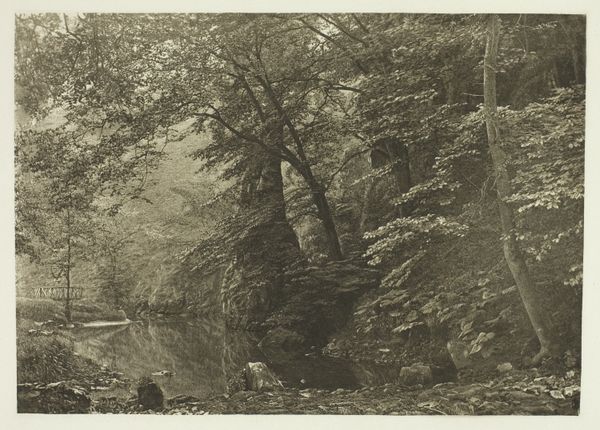

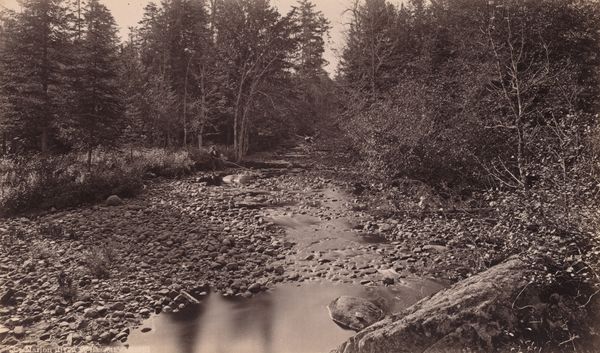

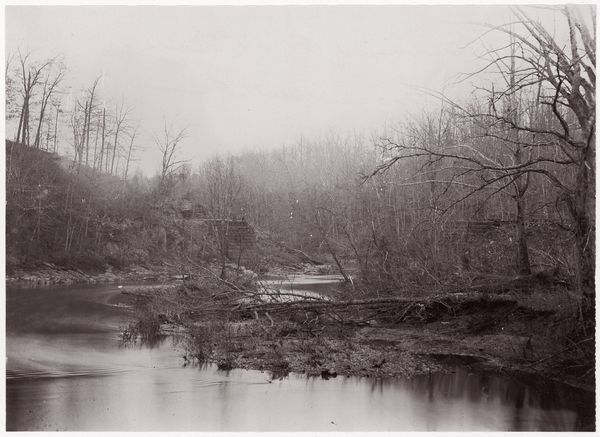

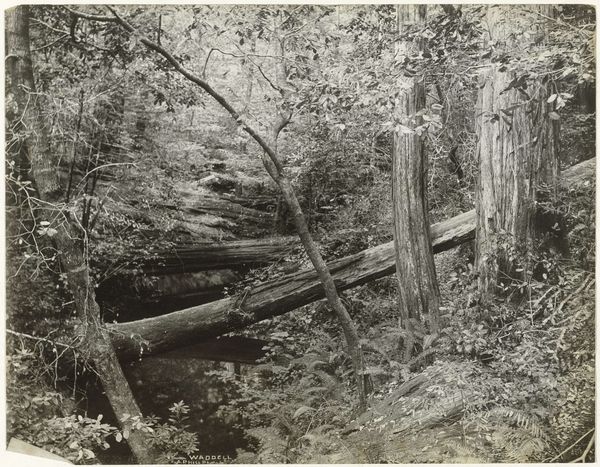

Editor: We're looking at "The Wissahickon Creek near Philadelphia," an albumen print from around 1863, by John Moran. The water looks so still and reflective, and the whole scene feels very dense and…contained. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a potent representation of the 19th-century American landscape, ripe for unpacking. While seemingly a serene natural scene, it's crucial to remember the context: this image was created during the Civil War. How might that influence our reading of this “natural” landscape? Editor: Hmm, the Civil War. So, this isn't just a pretty picture? Curator: Precisely. Think about the Hudson River School, the movement Moran was associated with. These artists often depicted nature as sublime and untouched, reinforcing a sense of American exceptionalism. But what does that ideal mean when the nation is fractured and embroiled in conflict, especially regarding slavery and indigenous dispossession tied to that ‘untouched’ land? This invites us to consider who benefits from such a representation and whose narratives are erased. Editor: I see what you mean. It’s like, this idyllic image is a way to gloss over the realities of the time. Is there any symbolism? The fallen log? Curator: The fallen log, the dense, almost claustrophobic, foliage… these elements could be interpreted as signs of disruption or the darker sides of American expansion. Moreover, photographs like this contributed to a broader discourse about American identity and land ownership, deeply intertwined with race, power, and national mythology. Consider, how was access to this ‘untouched’ nature racialized and gendered? Editor: Wow, I hadn't considered that at all. It's so much more complex than I initially thought. Thank you! Curator: Absolutely. It’s in these critical analyses that we unlock deeper truths about not just the artwork, but ourselves and the historical narratives we continue to inherit and perpetuate.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.