drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

sketchbook drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

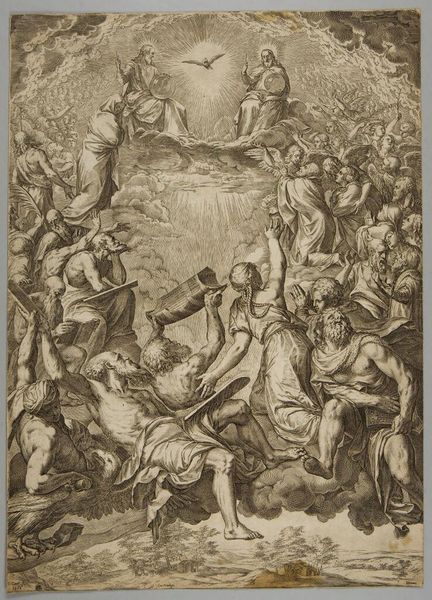

Dimensions: width 400 mm, height 531 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Bartholomeus Willemsz. Dolendo's "The Assumption of Mary," created sometime between 1580 and 1626. It’s an engraving rendered in ink. Editor: It's quite dynamic. The upper portion, especially, feels buoyant, almost ecstatic, with its swirling figures and upward momentum. The division into upper and lower halves, however, feels a little disjointed. Curator: Absolutely. It’s a prime example of Mannerist style, with that distinct emphasis on exaggerated forms and dramatic composition. Look at the technical skill required to create this through engraving. It shows a culture of skilled laborers producing prints that circulate and disseminate religious narratives to wider audiences. Editor: Precisely. And it's interesting how the lines create such depth and texture, especially in the clouds and drapery. Notice the almost chaotic energy versus the more earthbound stillness in the lower register depicting the apostles at her tomb. It's a calculated tension, I think. Curator: Speaking of the tomb scene, observe how it portrays a patriarchal reaction to the holy mother ascending to Heaven. This brings the politics of that imagery back down to earth and offers social context on how Dolendo and his workshop's works spoke to and affirmed the established Church doctrine. Editor: That is undeniable, but observe also the gaze. All eyes lead upward, drawing the viewer into the ascending action, transcending earthly bonds towards this celestial moment through compositional rhetoric. Even in the apostles' gestures, there’s a sense of wonder that carries us toward Mary’s haloed figure. Curator: And those keys there. Given how prints were commonly made in workshops for sale or to be displayed publicly or privately, one can wonder whose workshop these keys would open. Did it unlock a new path into Dolendo's career or to more prestigious projects commissioned by the church or patrons? Editor: You make a critical observation that enriches how we decode this piece beyond devotional illustration to the level of artistic enterprise and societal value attached to printed imagery. This allows us to connect deeply with its material origins, but it doesn’t prevent us from seeing, from feeling, that divine upward thrust, too. Curator: Precisely, it is precisely because it carries this weight and depth to both production and visuality that it is so beautiful to study here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Indeed. It’s a privilege to explore these multifaceted pieces and uncover fresh dialogues in historical artworks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.