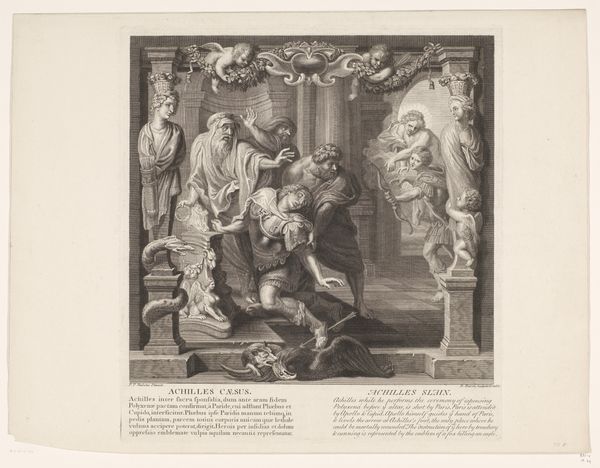

print, engraving

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

baroque

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

#

pencil art

Dimensions: height 75 mm, width 80 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me immediately is how domestic and chaotic the scene feels, especially for an illustration destined for Boccaccio's Decameron. Editor: Indeed, there is a fascinating tension. Here we have an engraving from 1697 by Romeyn de Hooghe, titled "Illustration for the Decameron by Boccaccio", currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. It is a genre scene executed with incredible detail. Curator: That is quite a contrast to the source material. The Decameron, known for its tales of wit and sometimes bawdy humor amidst the backdrop of the Black Death, this, however, reads almost as everyday life—the eagle perched on the man's hand seems particularly out of place given the cluttered domestic setting. Editor: Absolutely. I see the layering here not simply as narrative, but as a cultural commentary. We must recall that Boccaccio was deeply controversial. Placing the scene within what appears to be an alchemist's or physician's household normalizes, to some extent, that controversiality, bringing those grand tales into daily life. What do you make of the gender dynamics displayed? Curator: Precisely, I'm struck by the positioning of the women further back in the doorway—observers perhaps, but clearly demarcated as separate from the central action of the man and his falcon. I'd want to explore how that reinforces, or possibly challenges, conventional gender roles of the time. Who holds power, who can wield it? And who can be tamed? Editor: Contextually, these visual choices speak to the politics of imagery and the consumption of art. Prints, in the 17th century, had a certain reach that paintings didn't. De Hooghe's work here is making accessible in the form of print a story that challenges norms; disseminating counter-narratives through familiar visuals. Curator: And given that de Hooghe was Dutch, understanding Dutch society’s relationship to sexuality, class, and morality at that specific moment is crucial. It is, in many ways, holding a mirror to contemporary viewers in a time when print culture shaped the way those cultural dialogues evolved. Editor: This close consideration underscores the ongoing power of the artwork—it can speak to us today not just about the story, but also the complex dynamics of art in public discourse. Curator: I agree, it becomes clear that understanding those visual debates opens avenues for more incisive, layered meaning, reminding us the illustration contains its own compelling narratives beyond Boccaccio.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.