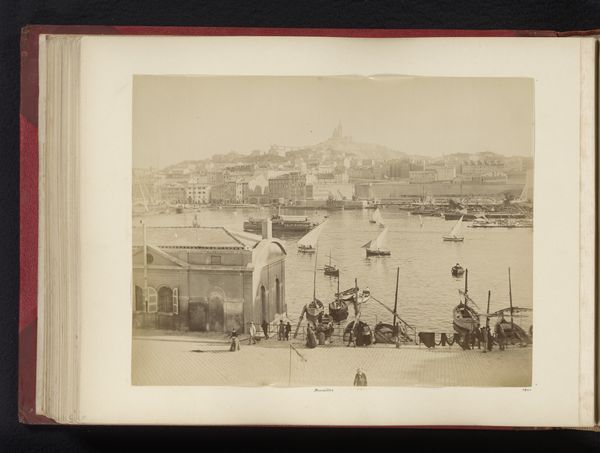

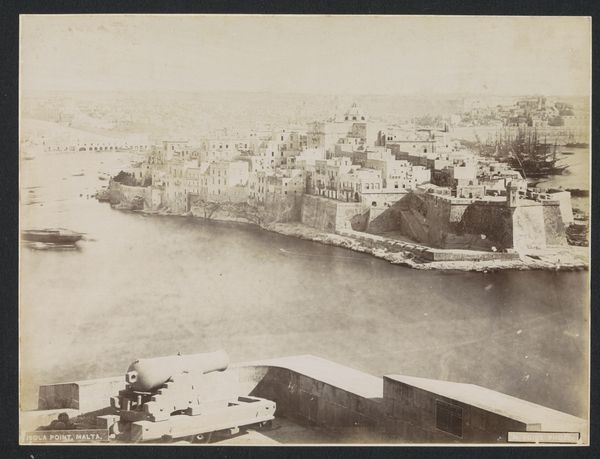

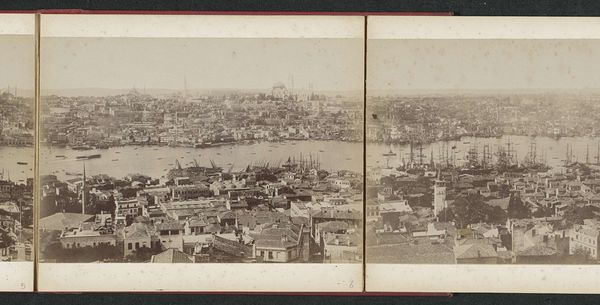

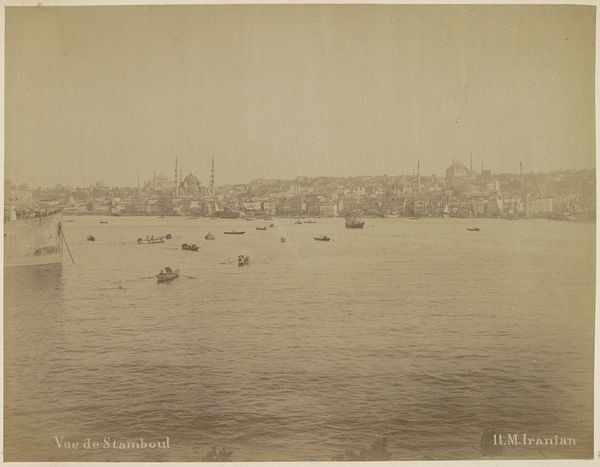

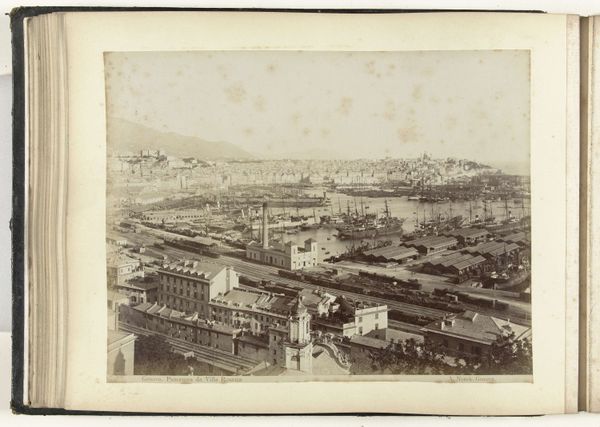

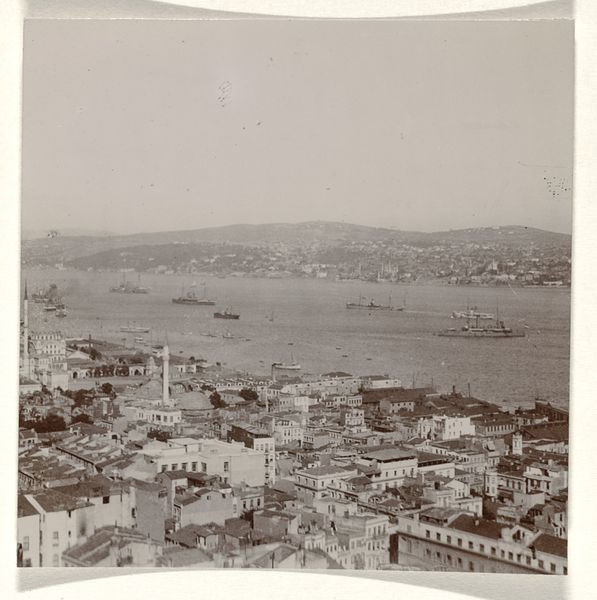

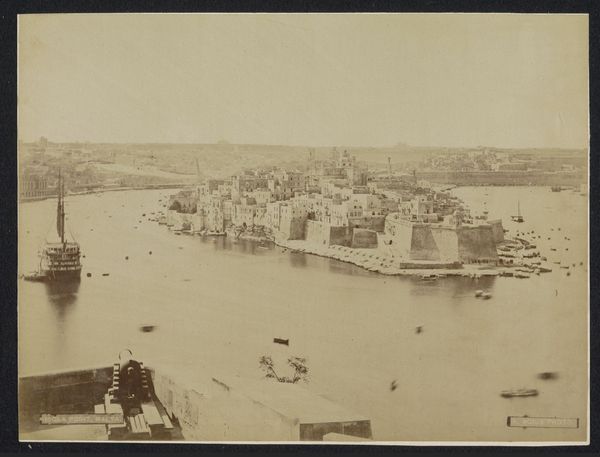

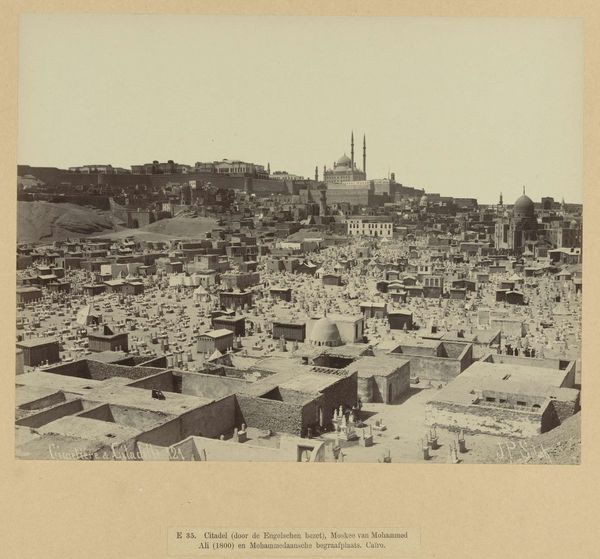

Groep van 55 foto's van Israël, Palestina en Syrië verzameld door Richard Polak c. 1867 - 1895

0:00

0:00

print, photography, collotype, albumen-print

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

collotype

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 558 mm, width 469 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: A touch of melancholy washes over me looking at this group of fifty-five photographs of Israel, Palestine, and Syria, compiled by Richard Polak sometime between 1867 and 1895. It’s mostly albumen prints, some collotype… evoking ghosts, almost. Editor: Indeed, the sepia tones lend a nostalgic air, almost romanticizing the scenes. But these images, though seemingly neutral landscapes and cityscapes, are loaded with the politics of representation during a period of intense colonial interest in the region. It speaks to the aesthetic of Orientalism, doesn't it? Curator: Yes, precisely. These are, after all, curated visions. Looking at this cityscape – the jumbled buildings along the coast – it’s tempting to get lost in the textures. Imagine wandering those streets, seeing those places. Yet the romantic, tourist gaze obscures layers of history, inequality… doesn’t it? What was the experience like for those actually living there? Were their stories and lives represented? Editor: Exactly! And what choices were being made about what to capture and, perhaps more importantly, what *not* to capture? Whose gaze informed the compositions? The collotypes especially, given their reproducibility, further disseminated this Western perspective, cementing certain narratives. These images need to be considered as documents, not simply picturesque views. Curator: It's almost too easy to forget that they're also objects with physical form – delicate, crafted with great care. Think about Polak selecting and arranging these prints, creating his own particular narrative. It reveals an act of profound intimacy, if twisted somehow through the colonial project. Editor: The intimacy exists alongside an inherent power dynamic, certainly. It reflects a wider trend of European documentation – appropriation, even – of other cultures and lands through photography. And what was done with them subsequently is not innocent. It can't be divorced from its historical role. Curator: I find myself both drawn to the strange, sepia beauty and repelled by the complex context. It makes you want to dig deeper, to know more about what isn’t immediately visible. Editor: Ultimately, it reminds us that every photograph is a political act, consciously or not. Especially photos such as these ones. Even these collected snapshots, from so long ago, reverberate through our present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.