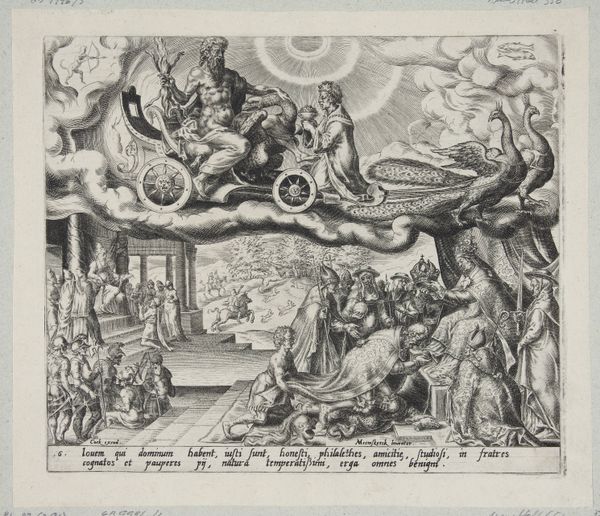

print, engraving

allegory

mannerism

history-painting

engraving

Dimensions: 206 mm (height) x 244 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Editor: This is "Jupiter," an engraving created by Harmen Jansz. Muller between 1566 and 1569, currently housed at the SMK in Copenhagen. I'm struck by its sheer complexity, like a dream crammed onto a single sheet. How do you even begin to interpret something so densely packed? Curator: That’s a fantastic question. The density is part of its Mannerist charm, a style that loved intricate detail and theatricality. Notice how Jupiter, with his lightning bolts and chariot pulled by peacocks, literally floats above the earthly realm. But it’s not just a pretty picture; it's a statement. The lower scene, crowded with figures, speaks volumes about power, influence, and maybe even the capriciousness of fate. What do you make of that contrast between the heavenly and earthly realms? Editor: It feels a little judgmental, almost like Jupiter's looking down on the messy, chaotic world below, handing out crowns to people who may or may not deserve them. Curator: Exactly! Think about the time. The late Renaissance was a period of massive social and religious upheaval. Artists used allegory to comment on everything from politics to philosophy, hiding their critiques behind mythological scenes. Those figures surrounding the coronation… do you see any that seem to stand out – either because of their posture or how the artist renders them? Editor: There are some shifty-looking characters on the lower right with swords and sinister glints. The artist emphasizes a tension. It makes the allegory feel really urgent and relevant. Curator: That’s it exactly. These engravings were mass-produced – relatively speaking! – and disseminated widely, fueling conversations and shaping opinions. Not unlike our Instagram feeds today, eh? Editor: So it's like a sixteenth-century meme, packed with hidden meanings. It really changes how I see it, less like a distant historical object and more like a very clever form of social commentary. Curator: And that’s the joy of looking closely, isn't it? Bringing the past into conversation with the present. There is always a new element of understanding just beneath the surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.