photography, airbrushing

#

pictorialism

#

landscape

#

photography

#

abstraction

#

airbrushing

#

modernism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to image): 9.1 x 11.8 cm (3 9/16 x 4 5/8 in.) mount: 34.5 x 27.5 cm (13 9/16 x 10 13/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

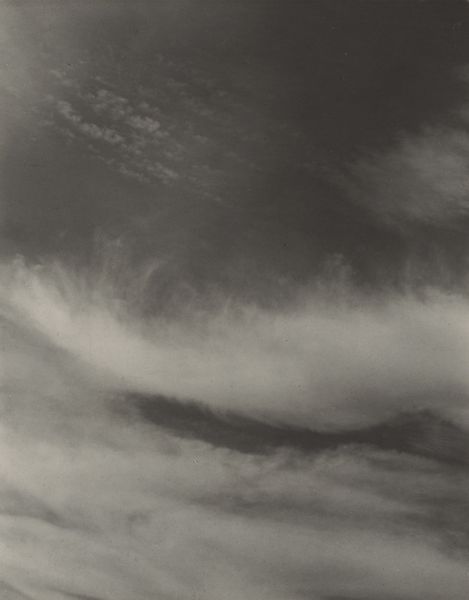

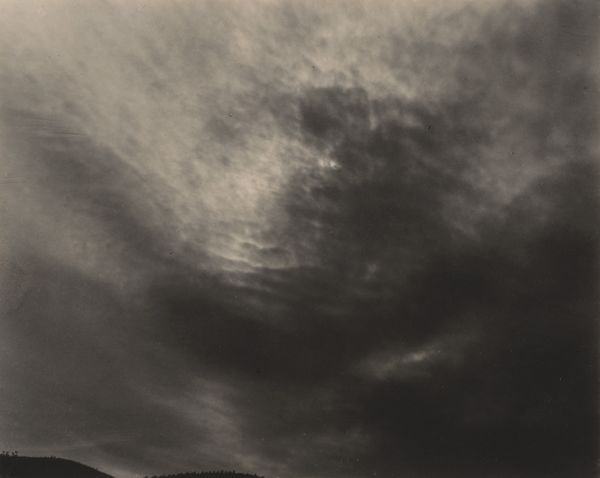

Curator: Here, we’re looking at "Equivalent," a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz, created in 1926. Editor: It's overwhelmingly…atmospheric. Like a captured breath before a storm. It almost feels like an abstract painting. Curator: Indeed, Stieglitz’s series "Equivalents," often featuring clouds like this, moved away from representational photography. He sought to capture emotions, inner states, distilled experiences rather than just a picture of a cloud. Editor: So, less about the sky itself and more about the *feeling* of the sky? He was actively using this visual shorthand as emotional metaphor? It’s a pretty loaded time to think about pure aesthetics: a year after the Scopes trial, a time of intense racial violence. Does abstraction offer him safety? Curator: In many ways yes, moving into the immaterial was safer than depicting bodies, identities, even still-lifes. But these cloudscapes have predecessors, too, particularly Symbolist art and literature where imagery evokes emotional and spiritual truths. Editor: True, and I'm drawn to this play between the objective reality of the photograph, which supposedly documents "truth," and its use for subjective, emotional expression. Is this tension itself political? Does claiming one's inner life *as* political revolt in the face of the very public traumas of modernity? Curator: Perhaps he considered inner life a universal experience – cloudscapes reflecting our common human condition. Stripped down of external, "earthly" concerns of class or race…or the kind of representational photography that was so pointed and political in the Harlem Renaissance a few years later. Editor: A bold statement. While I can appreciate the attempt at universality, can such a perspective erase lived experiences shaped by structural inequalities? Even the act of claiming universality becomes a power dynamic. Curator: Art, and its reception, always exists within those power dynamics. That push and pull is part of what makes it continually relevant, centuries after its creation. Editor: Right. Stieglitz provides an almost stark visual—which allows us to engage, challenge, question and re-contextualize from a variety of perspectives. A productive ambiguity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.