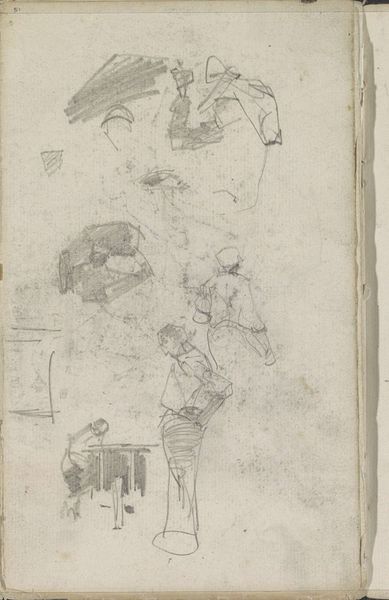

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

impressionism

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

pencil

#

academic-art

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

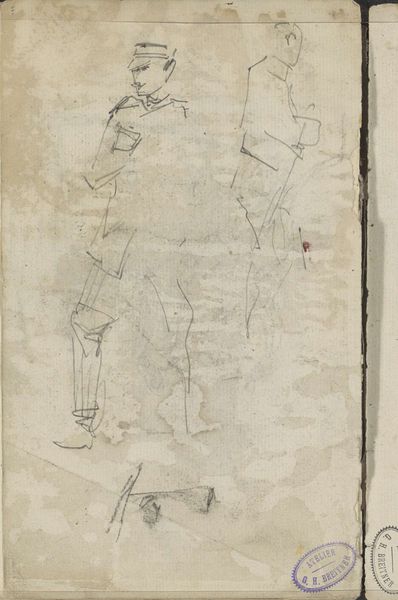

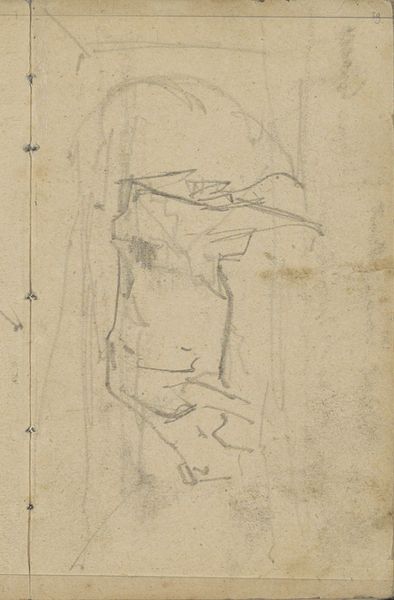

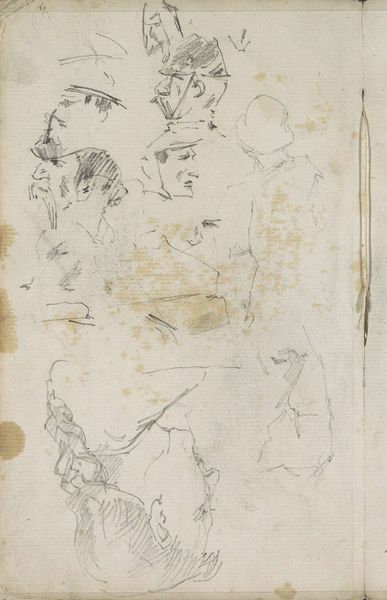

Curator: This is a study sheet by George Hendrik Breitner, created between 1880 and 1882, titled "Studieblad met hoofden en een staande vrouw"—Study Sheet with Heads and a Standing Woman. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection and crafted with pencil on paper. Editor: It strikes me as a wonderfully intimate glimpse into an artist's process. The casual scattering of faces and figures has a spontaneous energy, a refreshing contrast to more formal portraits of the period. Curator: Indeed. Breitner, aligning with Impressionist tendencies, aimed to capture fleeting moments, a stark break from rigid academic art. I'm drawn to the question of why these figures, these faces? Were they studies for a larger composition? Were they representative of an ideal from that time? Considering the sociopolitical ferment in Europe during that time, how did societal expectations affect the perception of the roles and expectations assigned to them? Editor: Symbolically, a study sheet is often associated with the intellectual's quest, seeking understanding through relentless practice. The recurring presence of human faces suggests a contemplation of identity and personhood, both enduring artistic themes, although one reads so much into mere sketches, so to speak. Perhaps Breitner was merely attempting to distill, as some cultures attempt to capture one's soul via image. The woman and the other sketched faces certainly resonate with vulnerability, particularly the figure at the top. I find the gaze unsettling. Curator: Right, considering the time in which it was composed and Breitner’s cultural milieu, those images may point to a burgeoning of Realism within the context of his Impressionist leanings. Breitner actively positioned himself amidst urban development and its effects. Perhaps this page can be contextualized by considering those disruptive dynamics and how they impacted society. How are power and identity interwoven? And what are the inherent, possibly harmful, structures present? Editor: So much hidden in apparent fragments. The sketchiness gives them an immediacy but, at the same time, obscures concrete meaning. To think these rudimentary outlines still spark this much dialogue over a hundred years later! It says so much about our inherent impulse to assign meaning even when intention is murky. Curator: Absolutely. These kinds of art encounters emphasize the power of both image-making and viewership as active construction—both historically and in the present. Editor: What begins as fragmented image begets endless discourse. A testament to the persistence of the visual and the viewer.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.