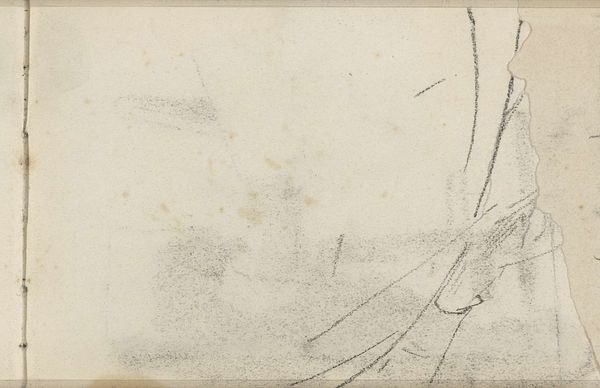

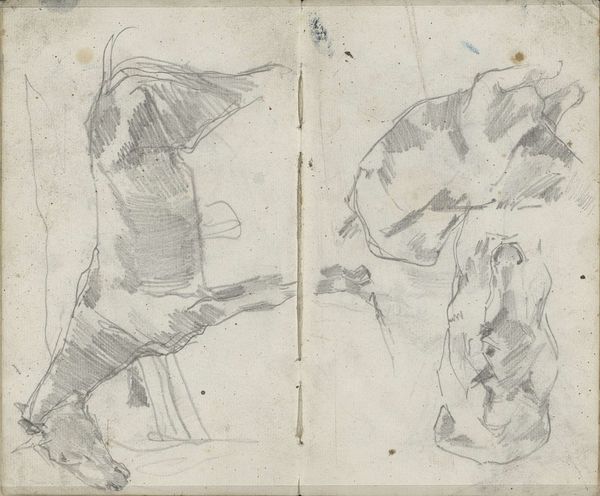

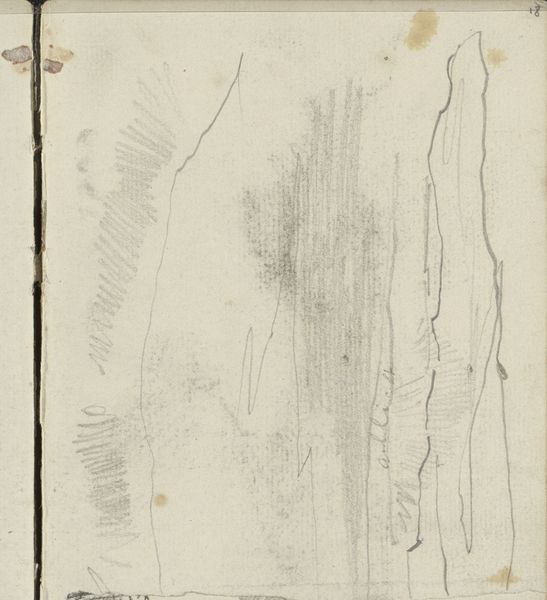

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

paper

#

pencil

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Louis Apol’s "IJsbergen," created around 1880, a pencil drawing on paper currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. The starkness of the icebergs against the pale background gives it a really lonely, desolate feeling, almost apocalyptic. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a powerful visual commentary on climate, perhaps unintentional. Apol's realism captures a scene, but through our contemporary lens, knowing what we know about glacial melt and climate change, it's difficult not to view this drawing as a document of a disappearing world. What social or political factors do you think might have influenced Apol, even unconsciously, during a period of increasing industrialization? Editor: That's a perspective I hadn't considered. I was just focused on the aesthetic impact and how cold and remote the image feels. Were there particular scientific discussions about the arctic environment circulating at that time? Curator: Absolutely. The late 19th century saw an increase in arctic expeditions, driven by scientific curiosity and colonial ambitions. Apol's work, while seemingly objective, participates in the construction of the Arctic as both a place of wonder and a resource to be exploited. This landscape wasn't just empty space; it was inhabited by indigenous communities. Do you notice anything in the drawing that reminds you of human influence or lack thereof? Editor: I don't see any explicit human presence, which contributes to the feeling of isolation. The marks, stains and smudges on the paper feel like chance encounters and imperfections and this accentuates the precariousness and temporal qualities, both literally and figuratively, reminding me of human effect and the passing of time, I guess. Curator: Exactly. The drawing isn't simply a depiction; it’s evidence. I appreciate how you bring into play the physical properties of the work and relate those aspects with temporal significance. The historical record of exploitation and the imminent impact that is present, with a lingering environmental danger on vulnerable communities. Editor: So it makes me think about the legacy and ethics in how we choose our subjects when creating our own work today, so it creates less harm to specific populations and groups. Curator: Precisely. By considering the artwork’s original context and acknowledging how our contemporary perspectives alter its meaning, we develop an ethics and responsibility. Thanks for making that critical connection.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.