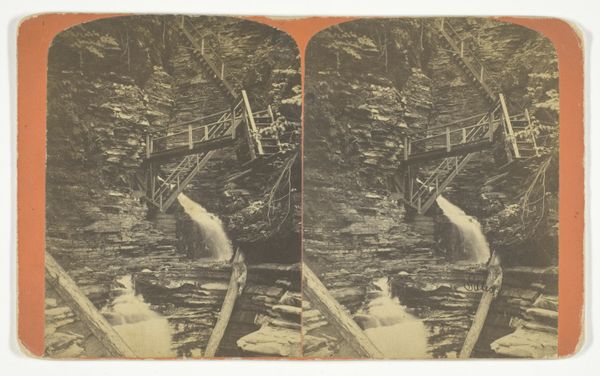

Reflection of El Capitain in the Merced River 1870 - 1871

0:00

0:00

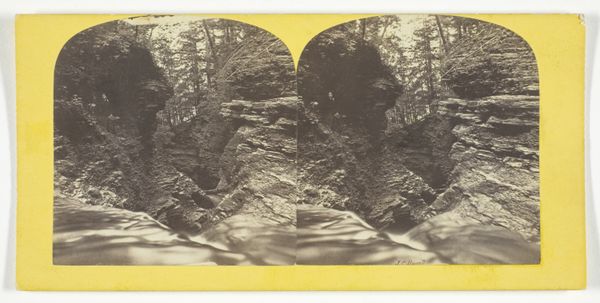

Dimensions: 8.4 × 7.9 cm (each image); 10 × 17.7 cm (card)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us we have an albumen print, a stereograph made by Anthony and Company, entitled "Reflection of El Capitan in the Merced River," dating from around 1870 to 1871. What strikes you immediately? Editor: It's eerie, this landscape split, almost bisected. The flipped reflection of El Capitan looms so large. What process was involved in achieving such clarity and depth of field in such an early photograph? Curator: The albumen print process was painstaking, involving coating paper with egg whites to create a glossy surface for the silver salts to bind to. And it was then mounted as a stereograph—intended to create an immersive 3D viewing experience. What ideology does it seem to represent? Editor: In the context of nineteenth-century America, wilderness held a particular symbolic significance. This technology makes it possible to bring to the world and share with anyone the wonder of experiencing this seemingly untouched, pure landscape. In the context of expansionist and colonial ambition this representation may function ideologically as the claim of something untouched, without considering that it IS a colonial ambition Curator: Precisely. And Yosemite itself was at a critical juncture, transitioning towards becoming a protected space but also undergoing the very visible interventions of tourism. It is fascinating the romantic portrayal is intertwined with land exploitation and Native people displacement. Editor: These prints offered a potent means to disseminate idealized visions of the American West but the production involved manual labour and depended on resources, especially in early commercial photography. What about this landscape image that sets the stage for the environmental crisis we are going through right now? Curator: A prescient question! Perhaps it’s in the implied relationship: The land reduced to an object of aesthetic contemplation, consumed passively. How did these images influence notions of land use? Who were they produced for and who did they exclude? Editor: I agree entirely. Looking closely, the labour of producing such a supposedly 'natural' image becomes clearer, reminding us that all representations, especially those masquerading as untouched reality, are crafted with specific agendas and for specific audiences. Curator: This image, far from being a transparent window onto nature, is actually a constructed narrative steeped in the social and political realities of its time. Its commercial and art making processes are one and the same. It really encourages looking to the material for truth, instead of trusting appearances. Editor: Indeed, let’s examine how we can transform that initial feeling of the sublime landscape into an alert understanding of art as part of historical, social, and production processes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.