drawing, print, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 130 mm, width 80 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

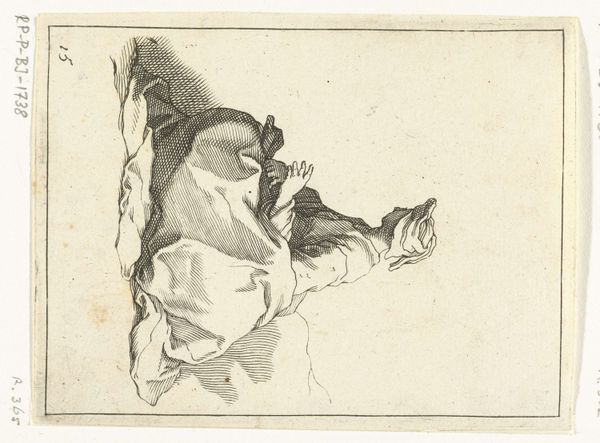

Curator: At the Rijksmuseum, we have this unassuming but subtly powerful piece entitled "Jonge boer," or "Young Farmer," rendered in etching, drypoint, and ink on paper. The work is attributed to Frederick Bloemaert, dating it to sometime after 1635. Editor: First thing I notice? The almost balletic pose. I mean, he's reclining, holding a rod up toward what looks like a beehive. There’s a whimsical air about the composition that belies any real hardship we might associate with farming. Curator: I'm glad you picked up on the tension. Bloemaert’s decision to elevate what some might consider mundane subject matter—agriculture— speaks volumes about the changing socio-political landscape in the Dutch Republic, particularly concerning the representation of class and labor. Editor: Labor...yes, that’s interesting. He makes the young farmer into some kind of heroic figure, you know? Look at how Bloemaert uses line—it gives his subject volume and makes his form almost classical in its depiction, yet he’s very relaxed. More ‘day off’ than ‘hard at work.’ Curator: Right, we have to see how he's romanticized. I find myself wondering, though, who was this art made for? Were these idyllic images intended to inspire pride within the farming class, or were they consumed primarily by urban elites seeking an idealized vision of rural life? Did it reinforce social divisions or bridge them? Editor: Ooh, good questions! Perhaps a bit of both? I imagine some found comfort in it while others were like, ‘Yeah, right! Try lugging fertilizer for a day!’ But on a simpler level, it shows us that images, even the most humble ones, are totally loaded with the artist’s take and those of the folks who see them, you know? What do we do with this view then? Curator: Absolutely, and I think engaging with such nuances forces us to rethink historical assumptions and contemporary values around labor, leisure, and the artistic representation of everyday life. Editor: You know, standing here, it hits me. Art is rarely just ‘pretty’ or ‘realistic.’ It is so weird, messy, beautiful—a dialogue in disguise that’s also timeless. It holds more truth and shows humanity better when it doesn’t try to have a message.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.