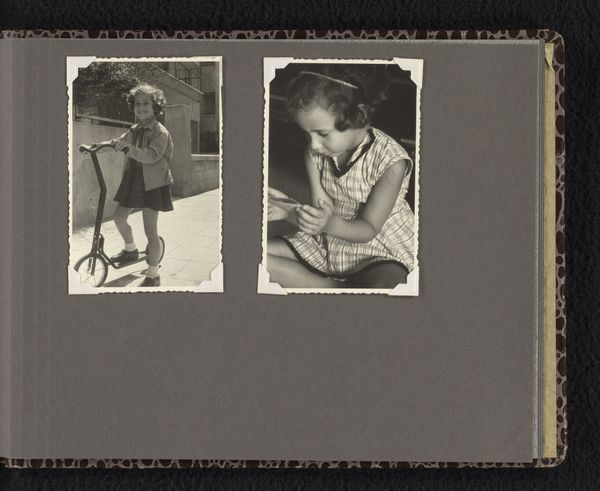

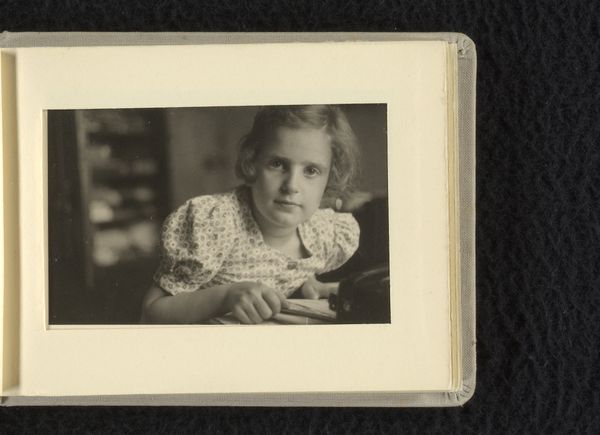

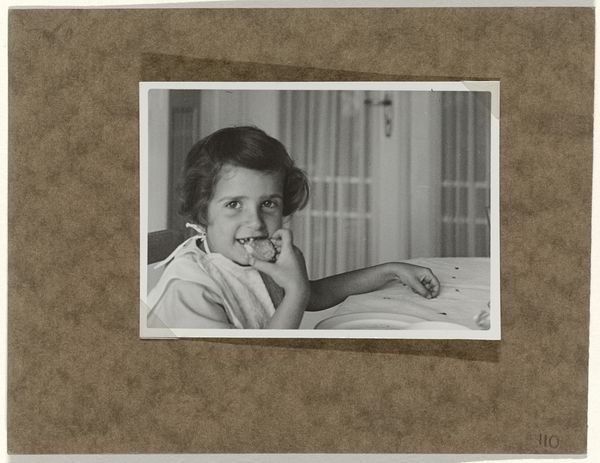

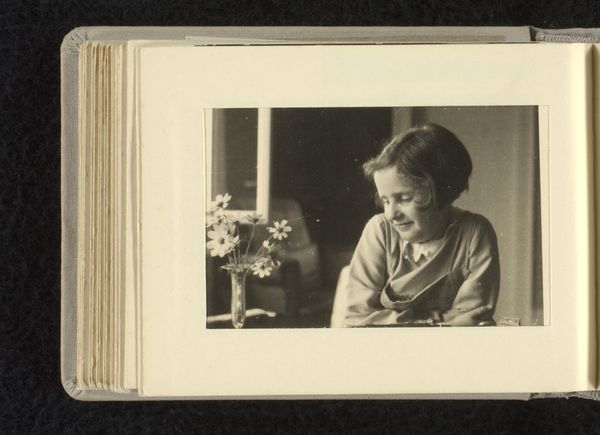

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

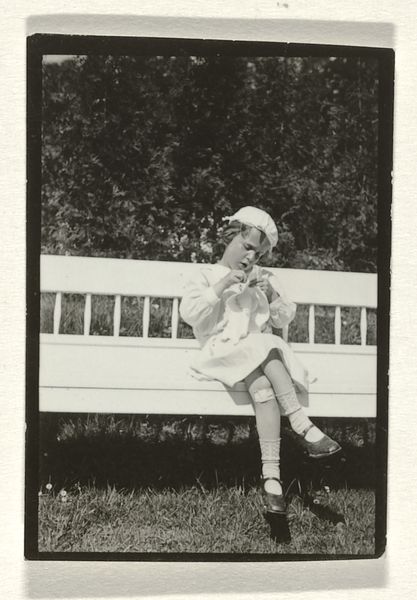

print photography

#

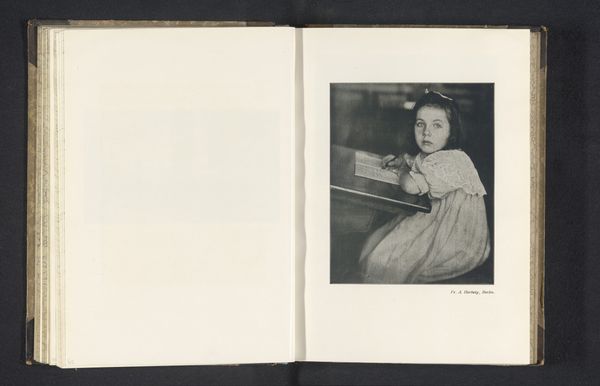

photography

#

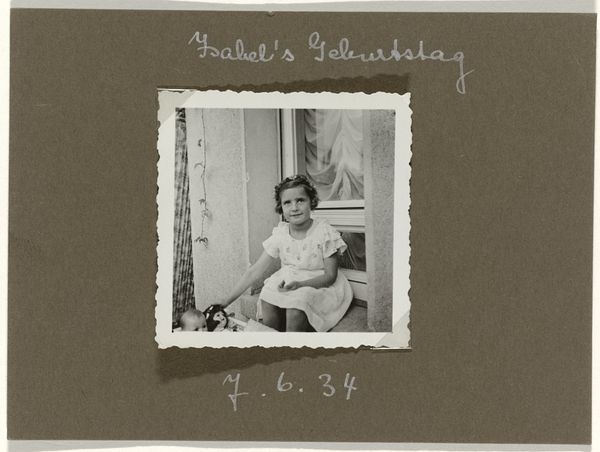

gelatin-silver-print

#

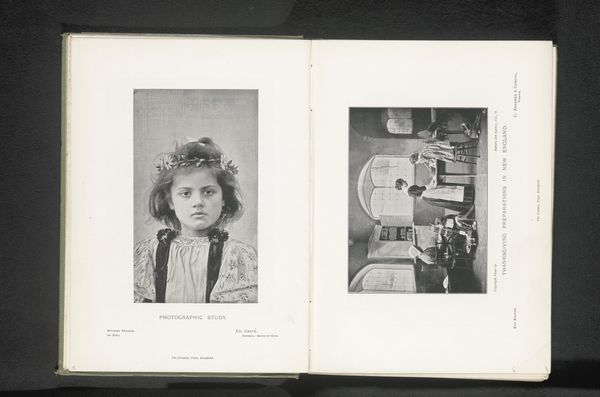

line

#

genre-painting

#

realism

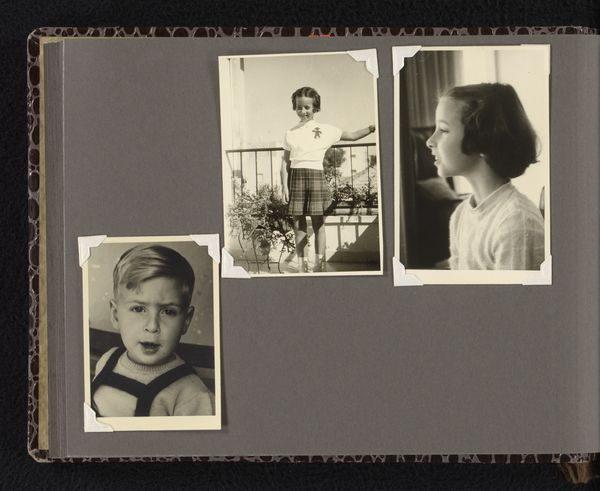

Dimensions: overall: 27.5 x 18.3 cm (10 13/16 x 7 3/16 in.) image (upper left): 18.2 x 12.3 cm (7 3/16 x 4 13/16 in.) image (lower right): 8.9 x 5.5 cm (3 1/2 x 2 3/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

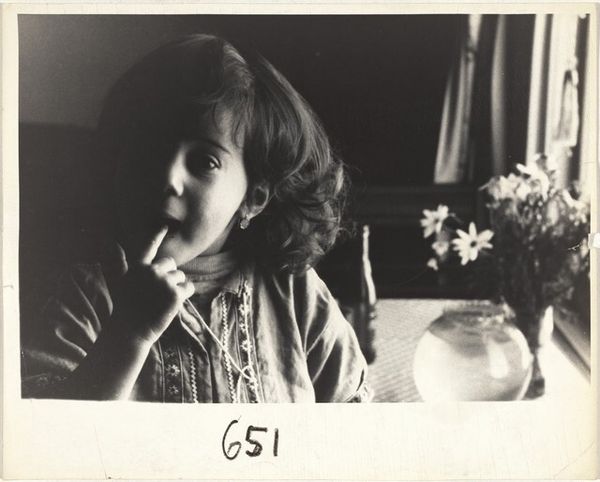

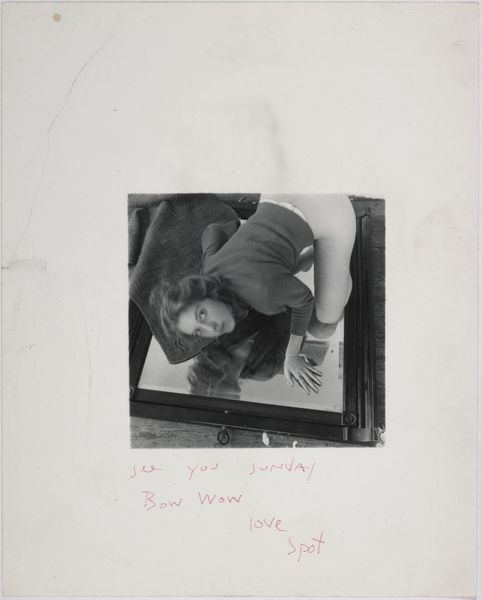

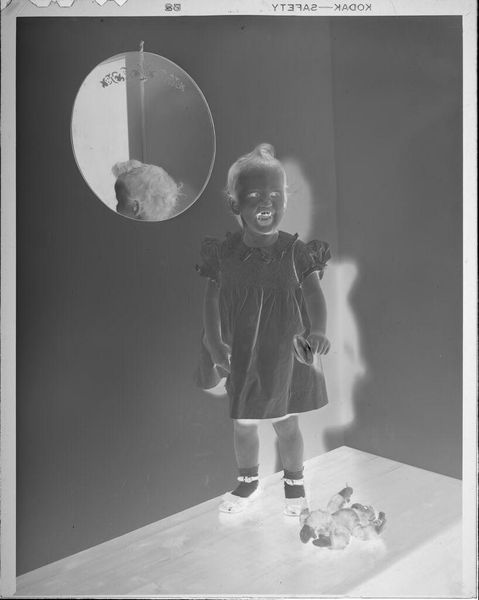

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, simply titled "Untitled," was taken by David Seymour around 1950. It offers a rather fragmented view, wouldn't you agree? My first impression is one of organised chaos. The grid-lined paper backdrop is covered in notations. Editor: Absolutely. Seymour seems to have photographed something akin to a photographer's proof sheet. It's more than just a photograph; it’s a record of the photo production process, revealing editorial interventions, revisions and practical choices relating to composition. Curator: Indeed, you have segments of the photograph featuring the children with their drawings, next to measurements, calculation numbers, a message struck through in pen, and some mathematical equations in red pencil. Focusing on the photographs of the children in this particular configuration, one can assume this arrangement had a clear significance. We also gain insights into the circulation and manipulation of images and their use. Editor: Right, it brings to mind Roland Barthes’s concept of the “punctum"—that small detail that unexpectedly pierces the viewer. For me, it's the raw vulnerability captured in the young girl's eyes as she writes on the board. How are these children, so soon after World War II, being asked to participate in the narratives about childhood? It is unclear the meaning behind the various notations of this fragmented piece as it feels like an incomplete story and reconstruction. Curator: The materiality of the print also intrigues me. Seymour used a classic gelatin-silver process, imbuing the image with a tactile quality, as well as rich tonal range. However, the notations add layers of meaning related to production value, that blur the distinction between the photograph itself and the work required for mass consumption. Editor: And yet, juxtaposing that process with the stark realities of postwar childhood pushes us to reflect on the narratives we construct and consume. Seymour's work, by capturing this seeming mundane moment, inadvertently gives us a space for reflecting on social identity of this girl during the mid-20th century. Curator: This is an unexpectedly revealing object. It's as much about the making of an image, as it is about childhood. Editor: I agree, it challenges us to examine not just what we see, but how and why we see it that way. It’s both aesthetically intriguing and prompts an essential critical examination.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.