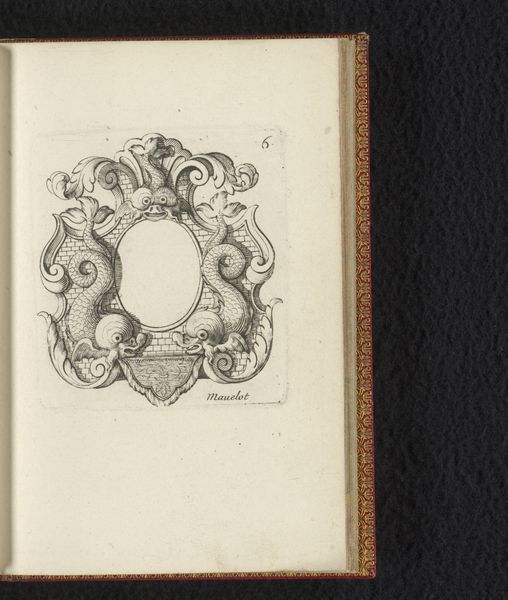

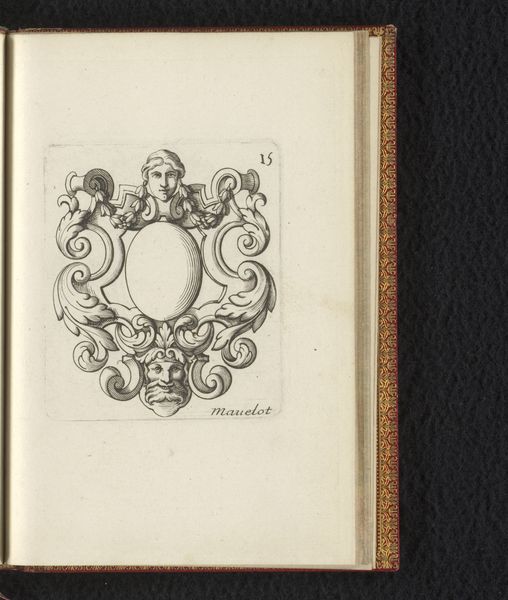

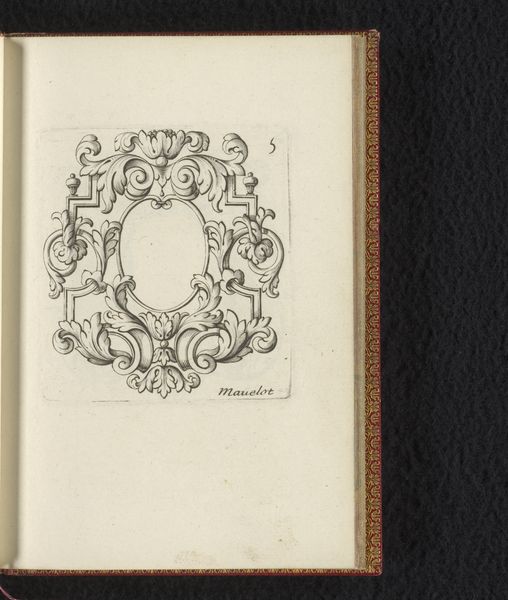

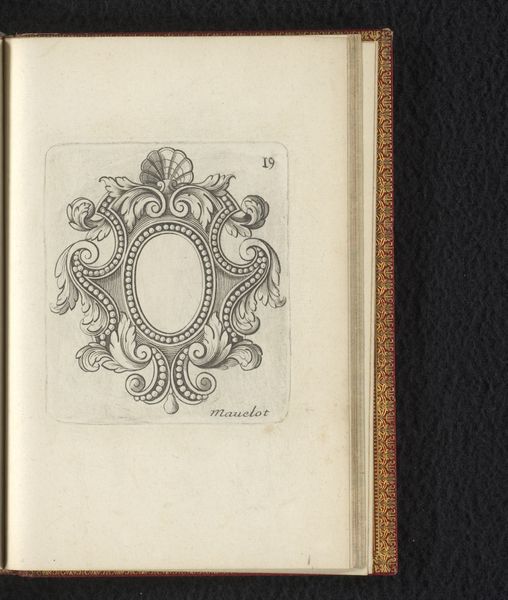

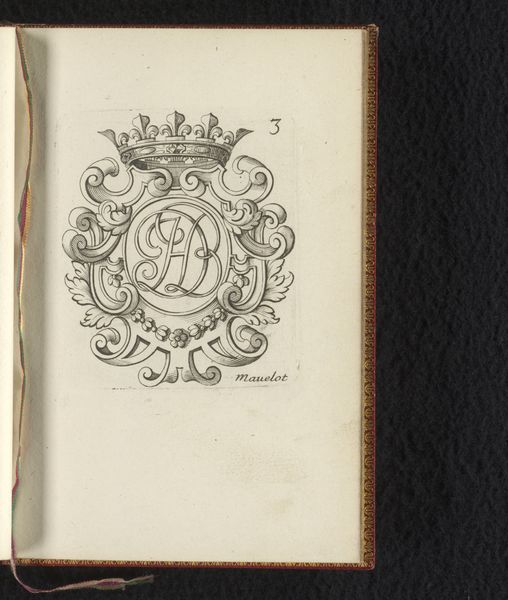

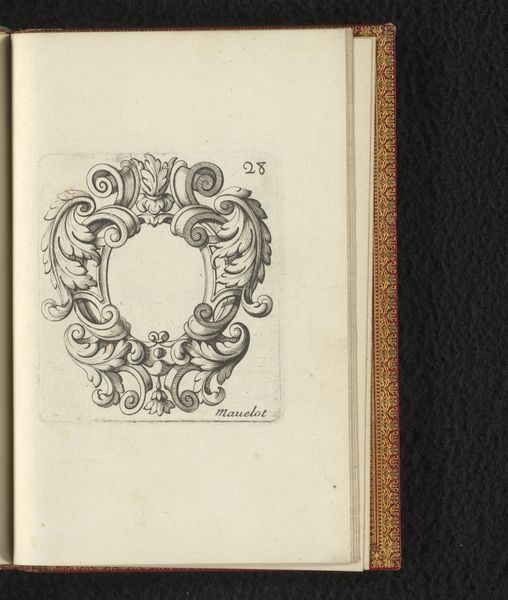

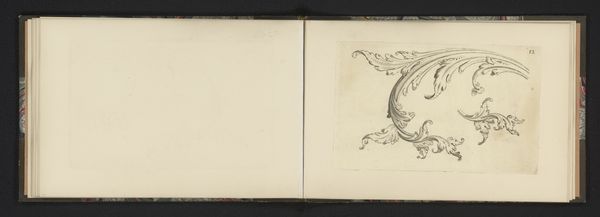

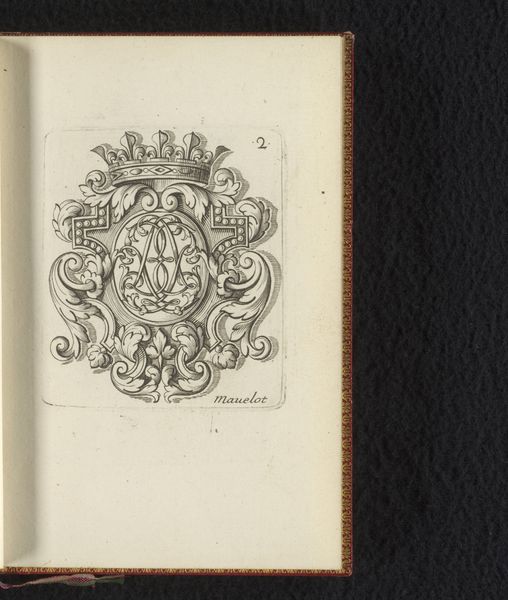

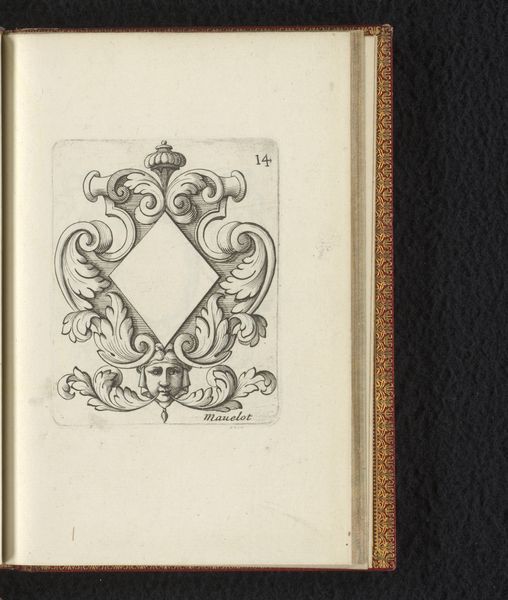

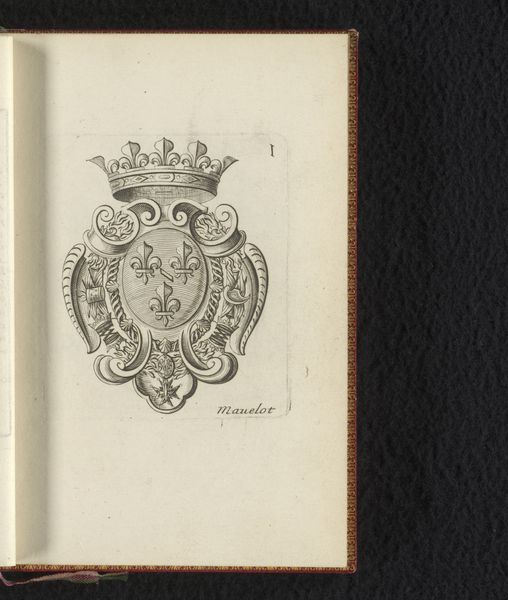

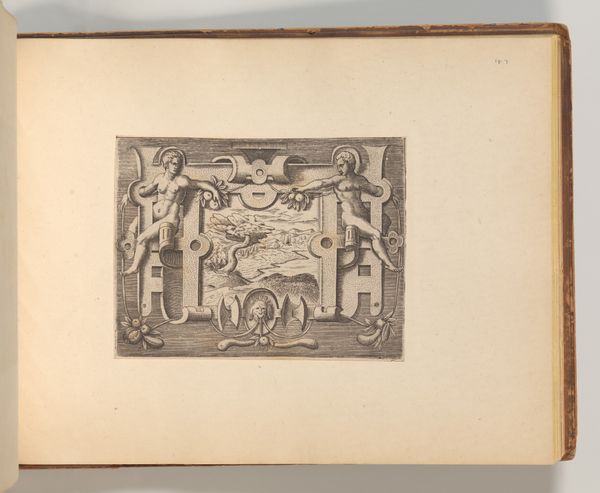

print, engraving

#

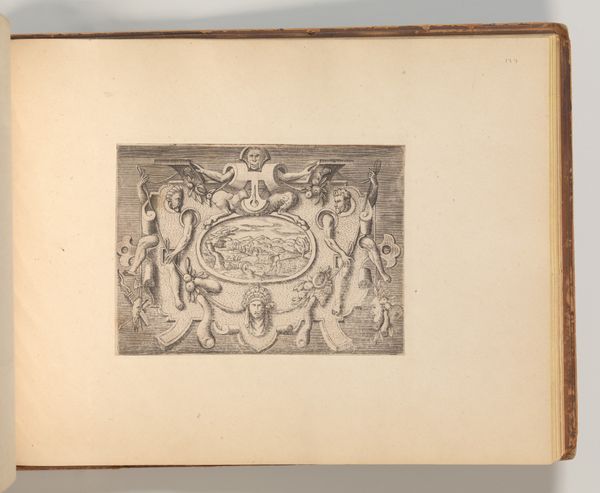

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

coloured pencil

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 73 mm, width 64 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This engraving, “Cartouche met gezicht omringd door zonnestralen,” made in 1685 by Charles Mavelot, has such a regal feel, even though it’s so small. The sunburst and symmetrical frame are so commanding. How do you interpret this work, especially given its historical context? Curator: I see it as a powerful statement of authority during the Baroque period. Consider the visual language at play: the cartouche, typically used for displaying text or coats of arms, here frames a void, presided over by a radiant face. The radiating sunburst, historically linked to royalty and divine right, positions that face, presumably male, at the center of power. Editor: So, it’s less about individual identity and more about embodying an ideal, maybe even an imposed one? Curator: Precisely! This idealized portrait transcends mere representation; it performs power. Ask yourself: Who commissioned this? What messages were they trying to send through its design and distribution? Remember, in the 17th century, imagery was carefully constructed and controlled to solidify social hierarchies. Even decorative prints can tell these kinds of stories about identity, class, and control. Editor: I never thought about engravings as carrying that kind of weight. So, it's about looking beyond the surface and questioning the forces behind its creation. Curator: Exactly! The engraving, seemingly decorative, acts as a carrier of ideology, reinforcing specific narratives. It is about unveiling the mechanics of power through the lens of visual culture. Editor: This really opens my eyes to how art, even seemingly innocuous art, functions within a power structure. I’ll never look at Baroque art the same way again! Curator: That’s the goal - to keep questioning and digging deeper!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.