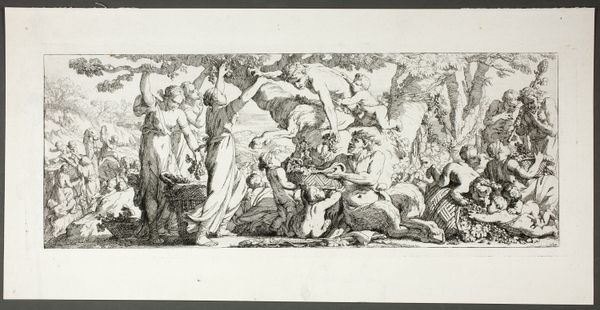

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 11 7/16 × 11 13/16 in. (29 × 30 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Ah, here we are in front of François Roëttiers’ “Bacchanal,” an engraving made sometime between 1705 and 1745. Editor: My first impression? Overindulgence sketched in delicate lines. It's like a party captured in a fever dream, everyone tipsy and tangled together. Curator: Precisely! It’s steeped in the Baroque style, so it embodies drama, extravagance and a sense of…theatricality. "Bacchanal" itself refers to the festivals of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, freedom, and ecstasy, though the Greek counterpart would be Dionysus, embodying liberation through music, theatre and intoxication, often defying social expectations, particularly for women. Editor: So, not just a party, but a ritual, a revolt, a moment where social constraints are loosened. Look at the bodies, relaxed and intertwined – is this freedom, or is it the precursor to a different kind of oppression? Because excess has a dark side, doesn’t it? Curator: Certainly, Baroque wasn't just about outward display, but it grappled with the tensions between pleasure and mortality. There's a definite erotic charge, yes, but also an undercurrent of melancholy. Like a hangover waiting to happen. Notice how Roëttiers uses light and shadow. Some figures emerge brightly, while others recede, almost disappear into the background. Editor: Right. The distribution of light complicates our interpretation; are we supposed to find pleasure, or repulsion? And how does the consumption play into it? Is there commentary on class, labor, on the access to "freedom"? Curator: A wonderful question and given that engraving would have permitted the print to be widely accessible, those are definitely salient entry points to exploring themes of over-consumption. Editor: Thinking about what "Bacchanal" would have signified then, and now – it makes you wonder how much the rituals of excess really change. Different drinks, different costumes, but the search for release, the negotiation with boundaries…it continues. It makes me pause and think about who exactly can find refuge from societal conventions, and whether it means safety for others. Curator: Well said, an engraving created nearly 300 years ago prompting reflection still resonates. I love when art does that. Editor: Me too. It becomes a mirror, distorted, perhaps, but showing something essential back to us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.