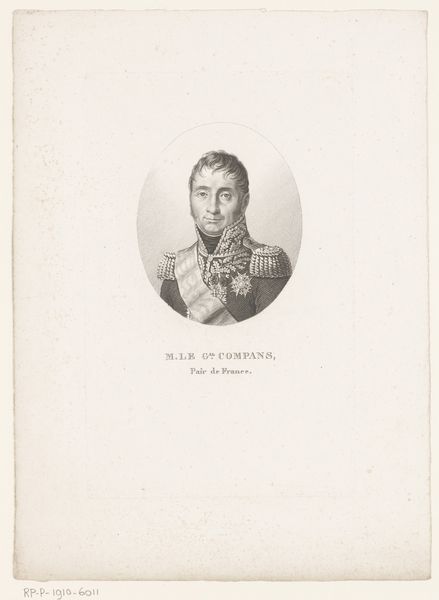

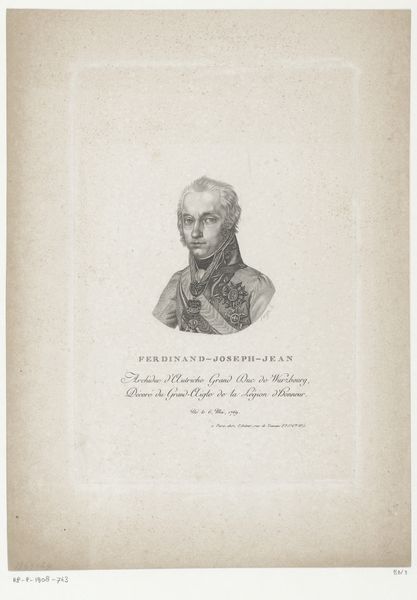

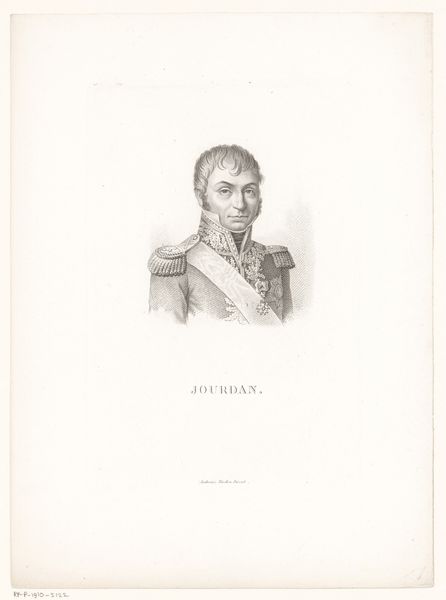

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

limited contrast and shading

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 218 mm, width 138 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a print entitled "Portrait of Jean Dominique Compans" made around 1818 by Charles Aimé Forestier. It employs engraving, a printing technique where the design is incised on a metal plate. Editor: It strikes me as quite stark. The subject’s stern gaze combined with the monochromatic tones creates a formal, almost severe atmosphere. What were engravings typically used for at this time? Curator: Predominantly for reproducing images and disseminating them widely. Think of it as a proto-photocopy, making art and information more accessible. The crisp lines would be crucial to render detail in maps, scientific illustrations, or portraits like this. The creation of a reproducible image involved meticulous handwork from a skilled artisan. This engraving’s stark aesthetic stems from its limited use of shading—contrasts, and layering marks that may speak to Forestier's approach in efficiently translating his sitter to a print. Editor: You make me think about the economics involved. It certainly democratized portraiture to some degree, but the engraver’s labor, the access to materials, and the commissioning of these works likely still involved certain echelons of society. A general like Compans likely held influence that enabled him to have access to representation, correct? Curator: Absolutely. The subject's military attire is very carefully rendered with various awards— the elaborate decorations indicate his status and valor. Neoclassical portraiture served a distinct social function: preserving the image of prominent individuals for posterity but, more immediately, consolidating and furthering one's social reach, so it begs the question how prints might accomplish such visibility? Perhaps it relates to distributing them as tokens. Editor: Tokens that speak volumes about power and legacy. Looking at it again, it’s interesting to consider this object as both art and propaganda, playing into the construction of heroism at a time of great social upheaval. Curator: The print serves as evidence of complex exchange and power at the turn of the nineteenth century and as an object of artistry. Editor: Exactly—a material trace of socio-political dynamics made accessible for our scrutiny today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.