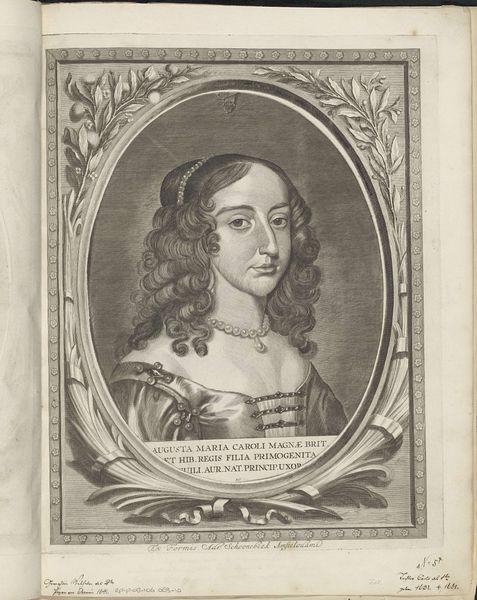

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 408 mm, width 282 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the delicate details, all achieved with lines, almost threadlike. It’s quite striking. Editor: Indeed. What we have here is a print, an engraving in fact, titled "Portret van Margaretha van Lotharingen" created sometime between 1644 and 1650, now held in the Rijksmuseum. The engraver was Pieter van Sompel. Curator: "Print." It is key to emphasize the medium. It impacts how the artwork functions. Its very purpose is circulation. Look at the framing; it mimics an oval picture frame, yet is crafted entirely from foliage. It reminds me of how prints made art available to a wider audience and suggests a democratizing force inherent in reproductive technologies. Editor: I think you hit a point there, but this work also highlights the hierarchical aspects of image production and dissemination. This is a portrait of nobility; its reproduction served to extend the reach and influence of that image, shaping public perception of power. Curator: Fair enough. And that’s heightened by the medium. Considering the labor involved in creating the original portrait, as well as the engraving process – the transfer of an image through skilled labor and specific material processes – the print becomes its own entity, carrying the aura of the subject and the process. The texture is fantastic too. Editor: I agree about the texture; Van Sompel employed hatching techniques beautifully. But considering its baroque aesthetic, what I see reflected most vividly is the fashion of the court in relation to statecraft: the pearl necklace and carefully arranged lace emphasize her position and contribute to the performance of power, if you will. Curator: So it functions almost like propaganda. Editor: Well, image management, definitely. The floral frame enhances it too, creating a sort of idyllic setting that suggests prosperity and divine right. This image isn't merely decorative; it participates in a much broader theater of dynastic display. Curator: Seeing how labor intersects with artistry in the engraving provides an additional lens. The engraver wasn’t just reproducing an image; he was also translating social status and power through the act of creation and distribution of material, to be handled, traded, looked upon. Editor: Absolutely, and thinking about the audience…those consuming such imagery reinforced certain values, aesthetic tastes, and socio-political norms of that time. The artwork served as both a record and a reinforcement of history. Curator: Fascinating. The complexities embedded within even seemingly straightforward portrait prints open pathways into labor, art history, and the social function of making things. Editor: Exactly. I always learn so much by digging into what portraits such as this signify culturally, generationally, and politically.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.