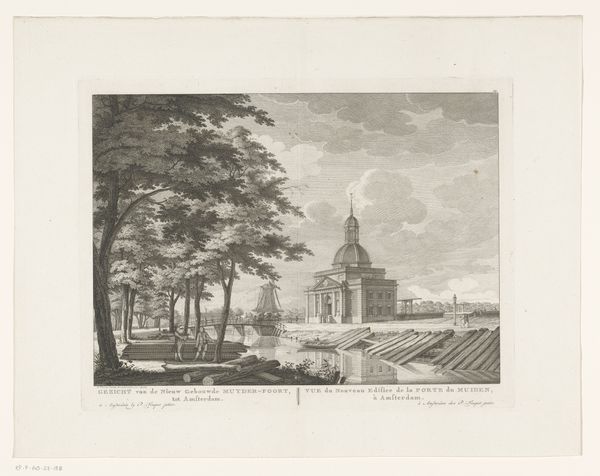

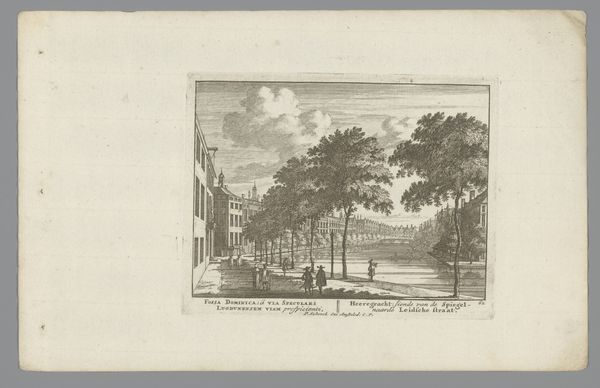

Dimensions: height 284 mm, width 354 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Barent de Bakker created this print, titled "View of the Second Muiderpoort", in 1771. It offers a detailed scene of Amsterdam's outskirts during the late 18th century. What are your first thoughts looking at it? Editor: Initially, I'm struck by how tranquil it feels. Despite depicting a gateway – a place of transit and potential control – the overall impression is quite serene, almost pastoral. The intricate line work and detailed rendering contribute to a sense of calm observation. Curator: Yes, that sense of tranquility is interesting, especially when considered within the historical context. The Muiderpoort was not simply a picturesque structure, but a crucial point of control for the city, managing the flow of people, goods, and potentially ideas. We could interpret the artist’s style as consciously obscuring those elements of state authority by drawing attention to daily rituals like fishing, or families picnicking. Editor: Precisely. And consider the positioning of figures within the frame; the figures in transit are dwarfed in scale when viewed beside those leisurely at rest within the lower and mid-levels of the engraving, hinting at a commentary around power and societal class. The artist chooses to draw the eye toward their relaxation. Do you see evidence of contemporary theories in that compositional choice? Curator: I think that's a sharp insight, situating the artwork within contemporary social dynamics! Beyond the immediate scenery, how the city used its defensive architecture in a period defined by increased Enlightenment ideals—rights of individuals over feudal restrictions, ideas about representative government over absolute rule. The location served practical military and commercial functions but becomes, through art, a place for philosophical considerations. Editor: And it pushes me to think about the very role of art during this period. How did prints like these shape the image, or rather, the brand of Amsterdam both for internal and external audiences? Did this romanticized view serve particular interests, or did it challenge others? Curator: Exactly! We're reminded to view art not only as aesthetic artifacts but also as powerful social and political actors that reflect or distort broader social truths. This is particularly so for urban prints like this one because their mass reproducibility facilitated the promulgation of specific perspectives to increasingly diverse populations. Editor: I agree. Viewing de Bakker’s print this way provides invaluable clues for unpacking the complex interplay of artistic representation, social power dynamics, and emerging notions of civic identity in the 18th century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.