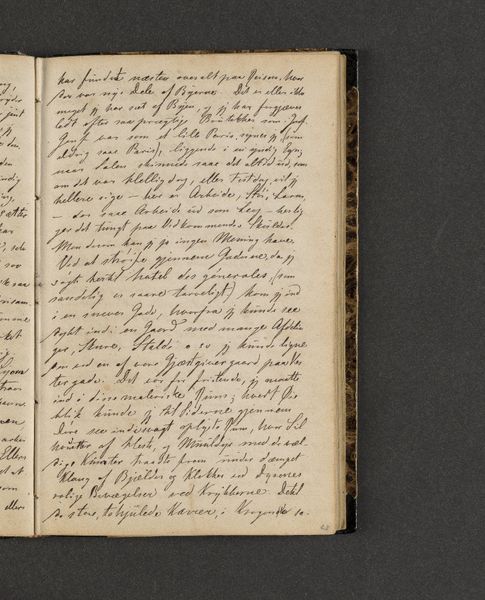

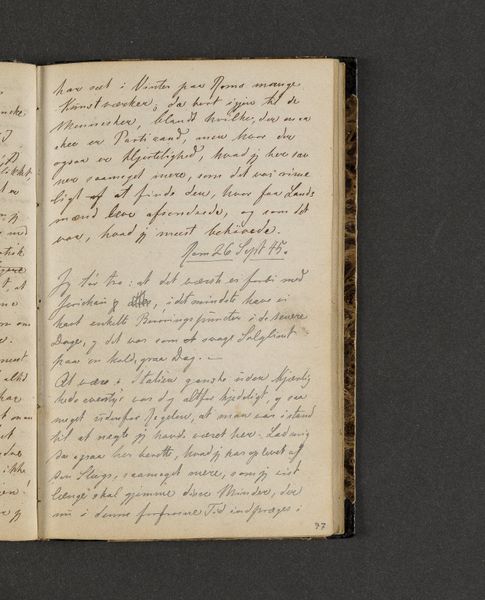

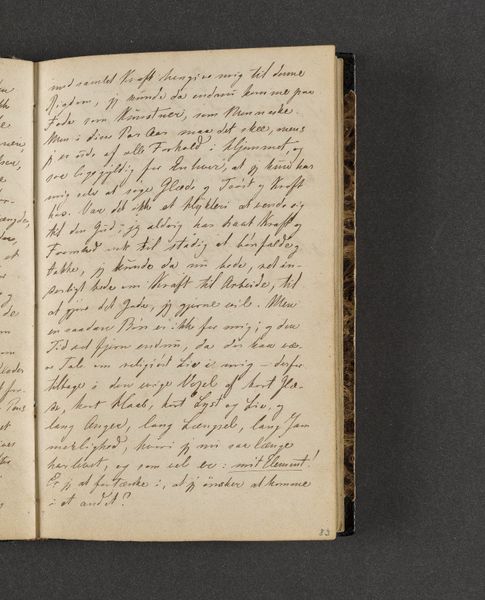

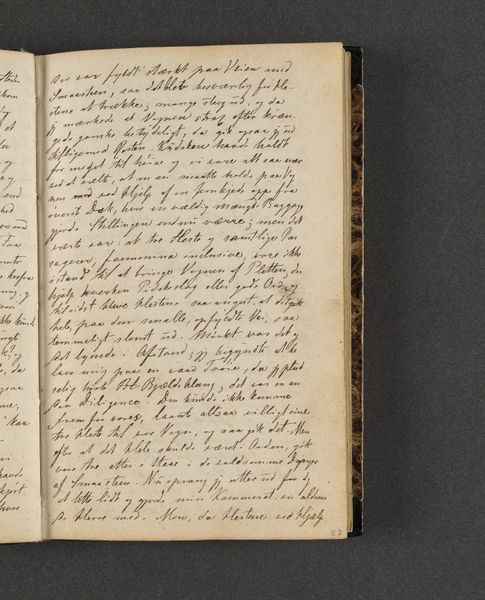

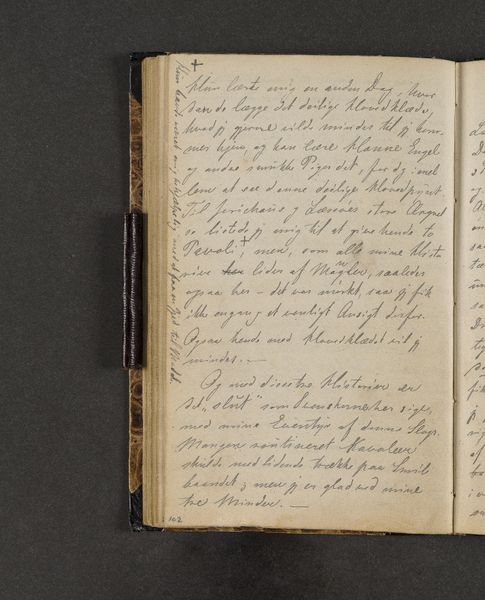

drawing, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

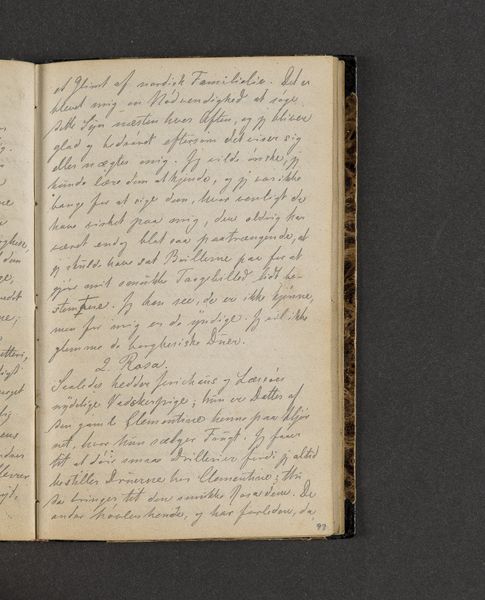

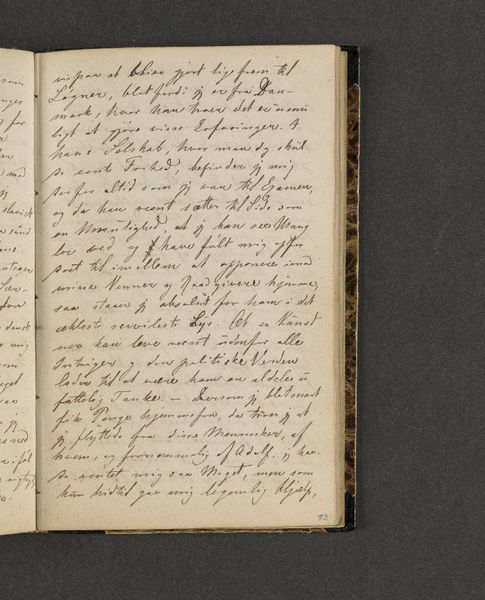

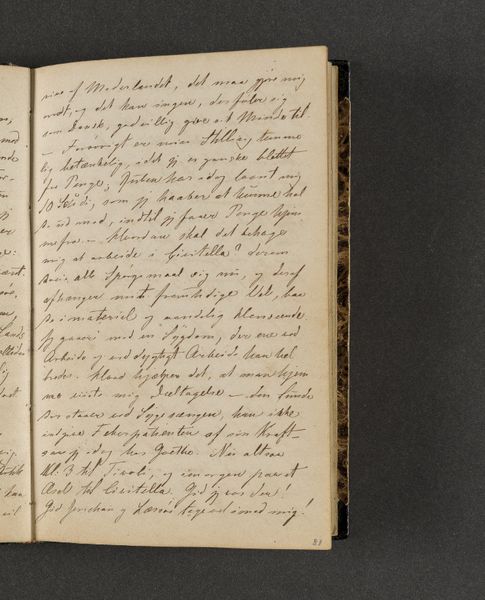

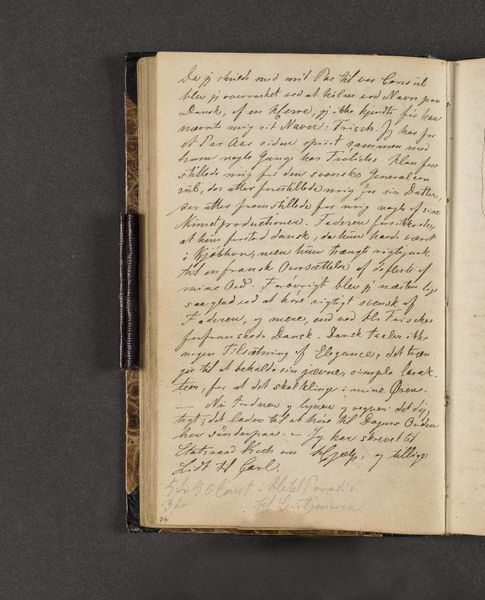

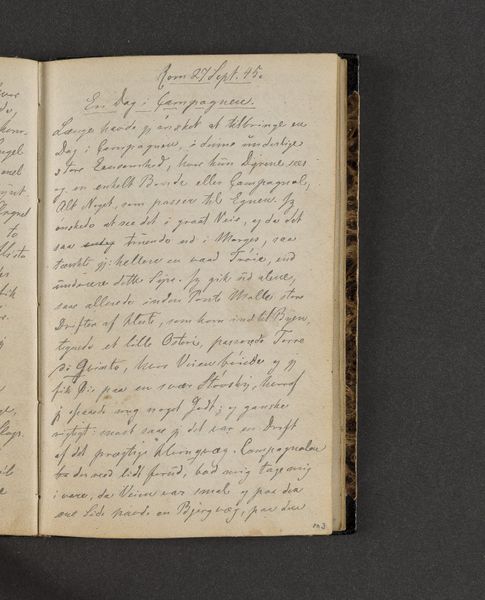

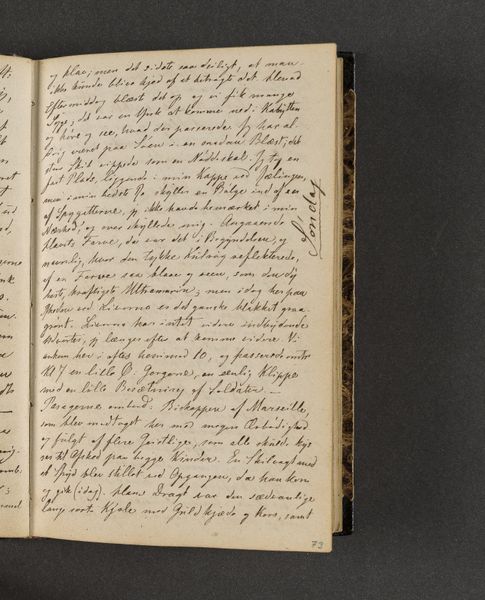

Dimensions: 161 mm (height) x 103 mm (width) x 11 mm (depth) (monteringsmaal)

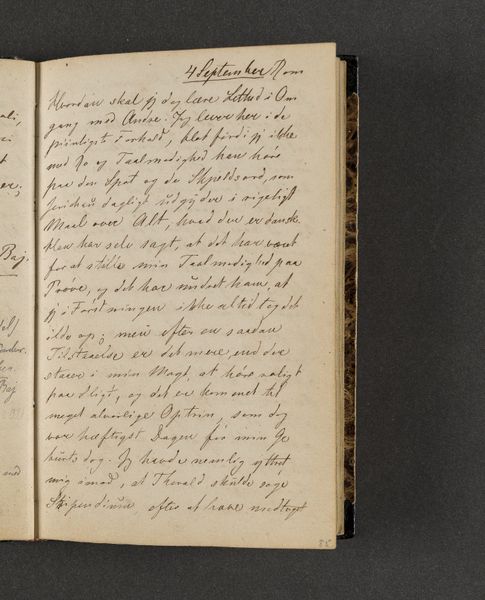

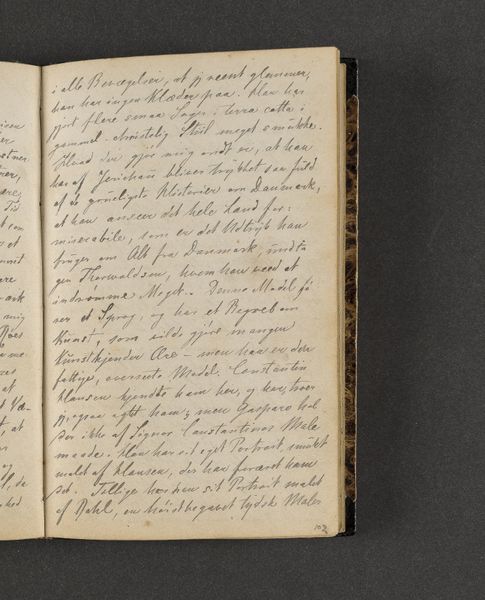

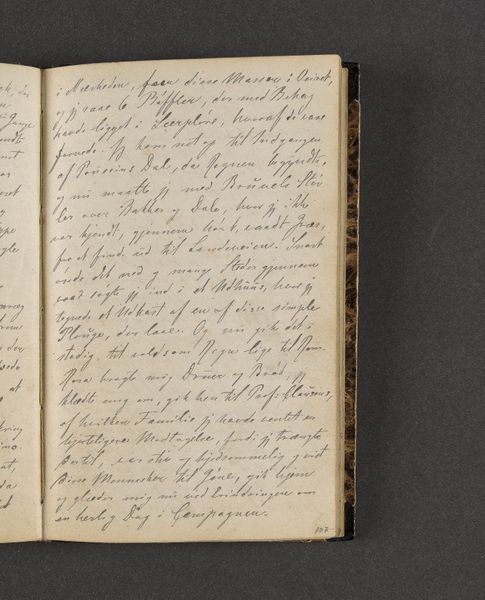

Curator: Here we have “Rejsedagbog,” or “Travel Diary,” a drawing created by Johan Thomas Lundbye in 1845, housed here at the SMK. It appears to be ink on paper. What's your first impression? Editor: My first impression is one of intimacy, of getting a glimpse into a private space. The script is dense, flowing across the page, like thoughts spilling onto the paper in real-time. There’s something vulnerable about it. Curator: I find that interesting because, for me, seeing the document itself in this form, as a fragment, reminds me that it once served a specific social function. These travel diaries, sketchbooks, and letter books provided visual evidence of journeys and also acted as proof of social networks and claims on cultural experience. Editor: Right, it's about situating this piece within a historical context, understanding that the act of documenting a journey wasn't just personal, but also performed a sort of cultural work. Who was Lundbye writing for, and what purpose did this text serve beyond simply recording observations? Was it also a tool for social mobility and establishing authority, given that access to travel was largely determined by class? Curator: Exactly. These visual and written records validated an individual's position within artistic and intellectual circles and aided in establishing authority within scientific or artistic arenas, if that was the diarists goal. In looking at the content of these writings we can often see Lundbye referencing artists and their artwork in efforts to form himself as a reputable member of Danish cultural society. It also becomes clear what ideological leanings may be motivating those associations. Editor: And what of the language itself? While inaccessible to most modern viewers without a translation, the script itself communicates a very particular form of cultural capital. Even illegible, the act of carefully rendering script could indicate to an educated audience that the writer possesses a certain skill set or access to knowledge. So what are we to make of it as modern audiences engaging with these class markers through these artworks in the gallery? Curator: It speaks to the politics of display, how historical artifacts can take on new meanings when they are removed from their original contexts and presented as objects of aesthetic contemplation. Editor: Absolutely. It urges us to interrogate the power dynamics inherent in art institutions, and question how our own interpretations might be shaped by them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.