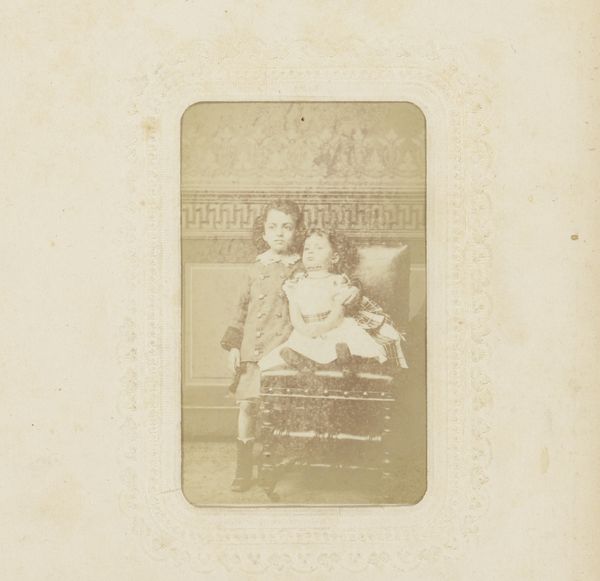

print, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

figuration

#

photography

Dimensions: 8.4 × 5.9 cm (image/paper); 10.3 × 6.2 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: I find something deeply melancholic about this early photograph, doesn't it strike you that way? Editor: Absolutely. Looking at John Jabez Edwin Mayall’s portrait of “The Crown Princess of Prussia,” created in 1861, one is immediately struck by the palpable weight of societal expectations placed on women, particularly royal women. Curator: Right! The future Empress Victoria. She looks burdened, despite the trappings of her station. The soft colors almost deepen the sense of gravity, like a faded dream. I mean, the image feels muted even beyond what you'd expect of a print from that time. Editor: Indeed. Notice how Mayall employs the conventions of portraiture to reinforce the princess's role. Her posture is stiff, formal, and reserved; the two children function almost as props within a dynastic tableau. This was, after all, a political marriage, and Victoria was essentially tasked with securing the Prussian lineage. Curator: And those children, though! The older one looks less than thrilled, while the baby stares out, utterly oblivious to the grand narrative being imposed upon them, onto their mother. It is almost claustrophobic in here. Editor: Exactly. The intimate sphere of motherhood becomes intrinsically intertwined with the political theatre of monarchy. Consider, too, that Mayall, as a pioneer in photography, was contributing to a shift in representation. This isn't just a painted portrait, but an ostensibly "true" rendering of the princess's likeness. Yet, how much truth can a carefully staged photograph really convey? Curator: True enough. The reality she lives may be nothing near what we assume when simply seeing a portrait. You can see something both beautiful and imprisoning, or not even notice these contradicting sensations coexisting in one frame, at the same time! Editor: Right. This piece encourages us to deconstruct notions of visibility, power, and female identity. Seeing it is about seeing beyond it too. Curator: I see what you did there. Thank you! Editor: It was my pleasure. I really enjoy engaging with you in conversations such as these, to deepen our insights around this portrait.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.