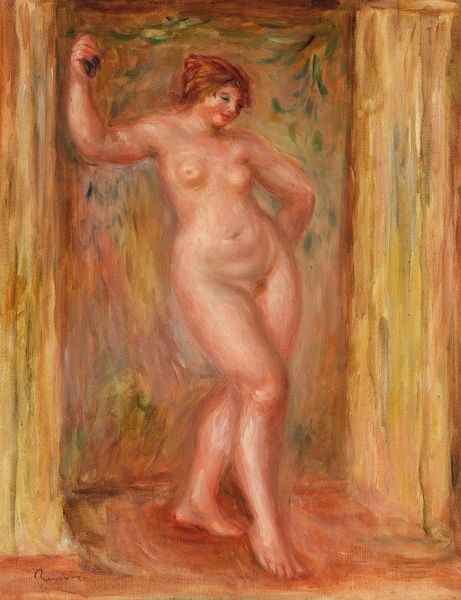

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

Curator: Standing before us is Renoir’s oil on canvas, "Seated Female Nude, Profile View," created around 1917, fairly late in his career. Editor: My first impression is of warmth. The color palette creates a sense of intimate and sensuous comfort. There is nothing severe or alienating about the figure. Curator: The subject matter aligns with Renoir’s exploration of the female nude as an embodiment of beauty and sensuality. Note that even here in his later years, we see the continuation of a romantic and idealized form, something he explored throughout his oeuvre. This piece also aligns with broader trends in early 20th-century French art, looking to redefine classic themes. Editor: The way Renoir uses light is remarkable, softening the model's form, seemingly avoiding the harshness that's common in similar works. It is almost dreamlike, presenting us not so much with a realistic body, but with an image that feels very much lived in. He seemed particularly concerned not with accuracy, but how our collective and subjective gazes have changed these depictions of the human body across history. Curator: It's precisely this effect of imbuing a body with that subjectivity through an almost blurry romantic idealization that has polarized audiences. While the painting clearly intends to celebrate the beauty of the female form, some viewers may find its interpretation dated. What does his use of light contribute to this sense of historical context? Editor: By softening edges and almost dissolving details, Renoir employs light to symbolize an enduring aspect of beauty rather than focusing on an individual or the historical body. His signature brushstrokes construct both figure and landscape, but also memory, emotion, and perhaps most fundamentally, our experience. In essence, this image taps into a long visual history through form and symbol. Curator: A painting, then, which holds up a mirror to both our artistic past and perhaps to our present sensibilities. Editor: Absolutely. It reveals how societal ideals and anxieties around representation still haunt how we view and interact with this figure today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.