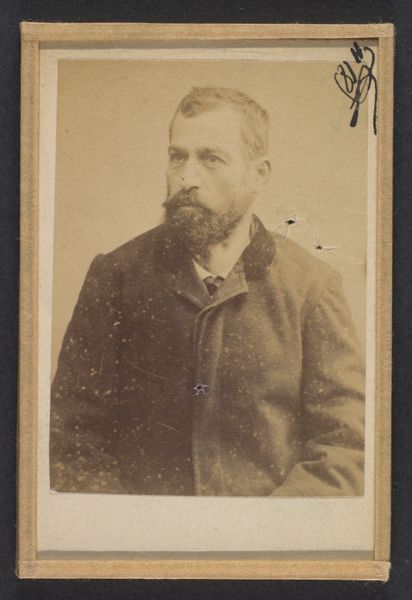

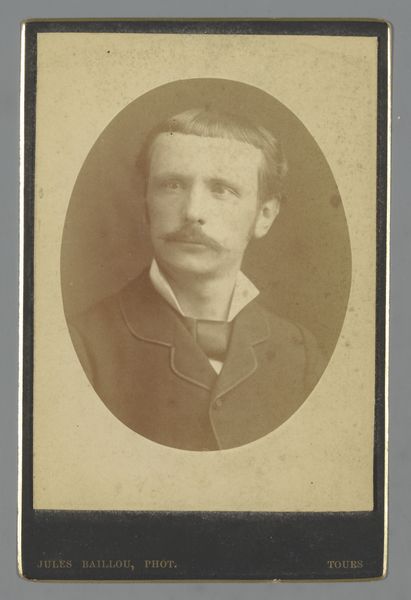

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

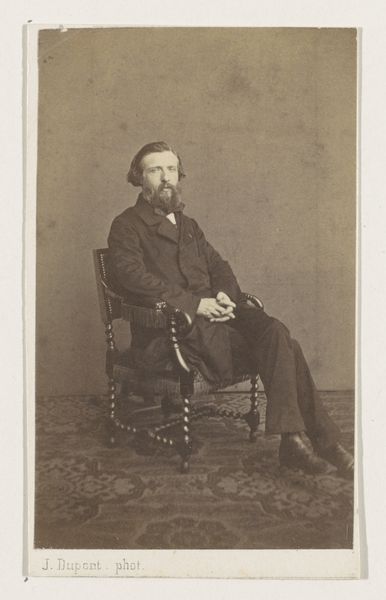

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 102 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

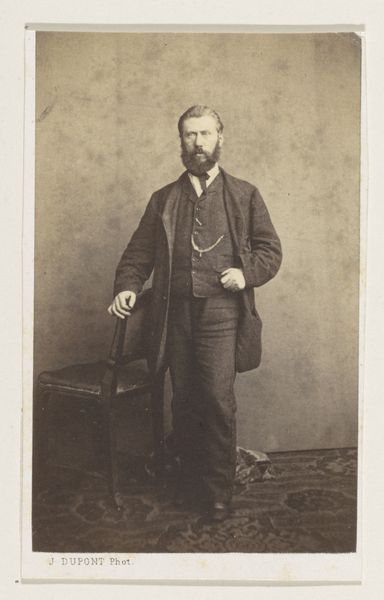

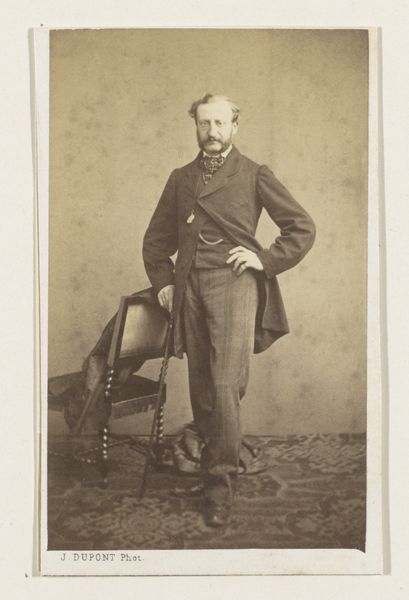

Curator: This is a photograph entitled, "Portret van de beeldhouwer Jean-Joseph-François van Hool, halffiguur," a gelatin silver print created by Joseph Dupont in 1861. Editor: It's immediately striking how contemplative and still the portrait feels. The sharp profile against the soft, neutral background makes the sculptor’s gaze particularly compelling, and that long, sculpted beard looks interesting. Curator: Exactly. Consider the context—Dupont’s photograph captures a moment of relative democratisation in portraiture. While oil portraits were still the realm of the wealthy, photography provided the emerging middle class with new opportunities for self-representation. This portrait allows us a rare glimpse into the life and self-perception of a 19th-century artist. Van Hool, the subject, gains a visual presence within a rapidly changing society. Editor: True, the materiality is fascinating. The gelatin silver print renders minute details in a rather tonal spectrum. I can't help but look at how Dupont manipulates light and shadow to reveal the planes of Van Hool’s face, accentuating the almost classical lines. It's so restrained and considered. Curator: It makes you think about who had access to visual legacy. For years, Black communities and working class people have been denied access to visibility in official portraits. What does it say about our current value system, who do we see as "important" enough to document. We need to really decolonise what we call history. Editor: Certainly, it brings the function of portraits into the critical lens, though as a study in light and form, it feels remarkably balanced and almost timeless. It's really that use of shadow to create shape I find so compelling. Curator: Ultimately, examining works such as Dupont's photography, we need to recognise art isn’t just aesthetically pleasing, but art shapes our understanding of society. We see who society wants us to look at. Editor: A lovely final reflection. It shows that portraits continue to fascinate and invite complex dialogue about not just visibility but, literally, what's in the picture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.