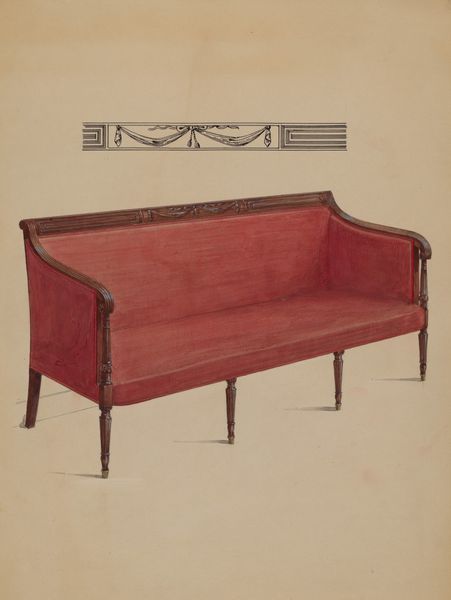

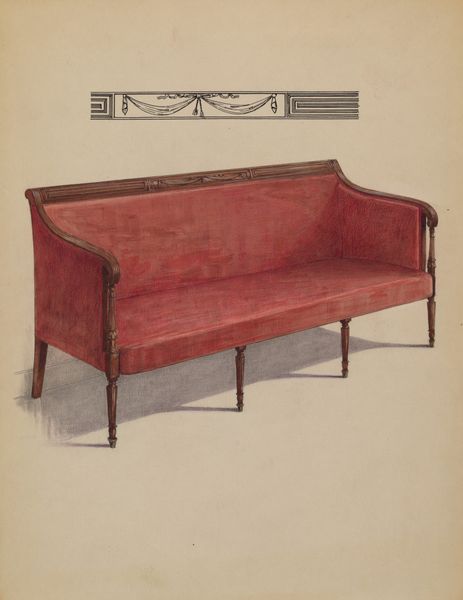

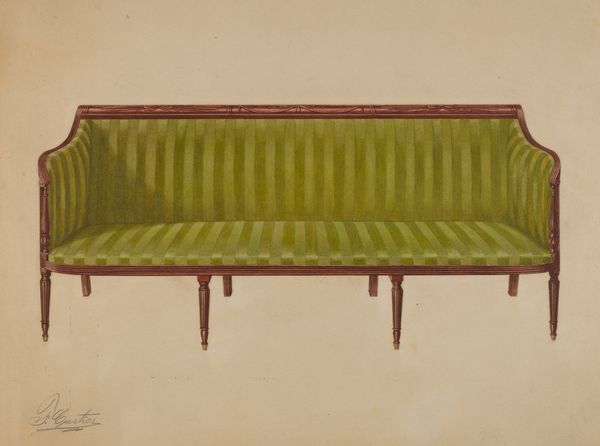

drawing, paper, watercolor

#

drawing

#

water colours

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

geometric

#

watercolor

Dimensions: overall: 23.1 x 28.7 cm (9 1/8 x 11 5/16 in.) Original IAD Object: 31"x75"x22"

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: There’s a real sense of stillness in this watercolor by John Dieterich, simply titled "Sofa." It was rendered in 1936 using watercolor on paper. Doesn’t it just beckon you to sit, rest, and… reflect? Editor: Absolutely. The rendering of this 'Sofa', in 1936, couldn't exist in a vacuum. Consider that, worldwide, a financial depression was at its peak—massive global joblessness, desperation, class division. This intimate sketch feels almost… reactionary, doesn't it? To consider this luxury item amidst widespread suffering provokes a whole host of socio-economic considerations. Curator: That’s a really important lens. But I also see the gentle wash of color, the meticulous rendering of light on the wood…it whispers of a quiet domesticity, an escape, perhaps a wish. You know, an artist dreaming up a more beautiful, restful reality when maybe their actual one was kinda noisy. Editor: Or a pointed commentary on exactly who gets to dream of rest. What I see is the potential irony inherent in focusing artistic skill and precious resources on depicting a symbol of comfort that, for so many during that era, was simply unattainable. It highlights divisions along class lines. Curator: Fair enough. I suppose the neutrality of the pale blue—a near absence of pigment really—contributes to that sense of…understated tension, maybe even unease, you mentioned. It isn't lush. It isn't inviting per se. It's almost clinical in its detached observation of something meant to inspire warmth and repose. Editor: Yes! Think of the broader aesthetics of 1930s design too—a conscious return to 'simpler' forms even when executed with expensive materials. It was an era wrestling with its identity as the world hurtled towards more political and economic instability. Curator: So the sofa here becomes more than just a sofa... it transforms into a loaded object signifying cultural complexities. It's fascinating how an everyday thing—painted so plainly—can reveal so much. Editor: Precisely. Viewing it through this lens adds new layers of relevance that allows a broader and more diverse public to potentially connect to it, across class, generational, and racial divides.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.