Copyright: Public domain

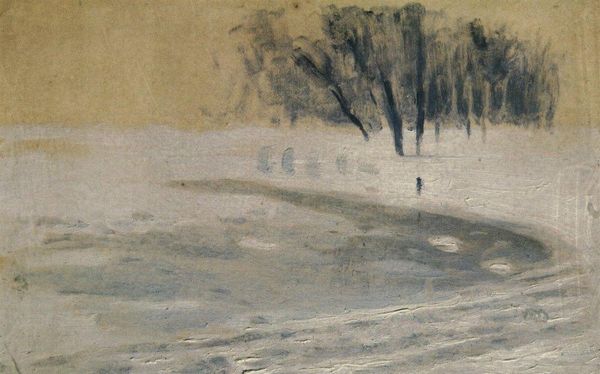

Curator: Claude Monet's "The Seine at Port-Villez, Pink Effect," painted in 1894, captures a fleeting moment along the river. Monet, of course, was dedicated to working "en plein-air" to document the changing atmospheres. Editor: My initial impression is one of profound quiet. The palette is muted, almost monochrome. A sort of hazy stillness permeates the scene. The composition appears radically simplified: vertical masses flanking a horizontal stretch of water. Curator: Absolutely, the apparent simplicity belies the intensive labor. Monet built a floating studio. The boats, canvases, paints, and the associated manpower to move these around would have been essential for executing this vision of the landscape. The economic support provided by Durand-Ruel afforded him time to create art without concerns about material comforts. Editor: Speaking of material vision, look how Monet has rendered the reflection of the trees. He's dissolving the boundary between the solid form and its ethereal copy, blurring the water's surface through distinct patches of pink, gold, and lavender. It verges on abstraction. He's captured a certain transience—the impression of light, atmosphere, and surface all interacting. Curator: Transience speaks directly to Impressionism, of course, but I think we can explore its material realities as well. In addition to focusing on its stylistic choices, we ought to question who owned the riverfront property where Monet established his landscape, where did he acquire canvases from, how many workers supported his process to execute this artistic statement? Editor: While important to acknowledge, that line of questioning takes us away from this remarkable formal construction, though! Look at the calculated asymmetry. A dominating dark mass anchors the left, balanced by diffused lighter tones on the right. The painting oscillates between defined shape and pure sensation. I think what remains vital here is this rendering of subjective perception. Curator: I see your point about formal harmony. And, considering that, the material conditions do shape that impression – Monet could have easily favored, for instance, other palettes given the range of pigments available in that era. This particular palette may not be accessible to a painter outside of specific socioeconomic parameters of late nineteenth-century French society. Editor: An interesting note! Thinking of how both conditions coalesce certainly enriches our viewing experience. It is certainly interesting to examine the tension and synthesis between intention and accident, form and substance that shape this remarkable vision. Curator: Indeed, perhaps by contemplating that convergence, we can better appreciate how artists and their artwork exist as product and a reflection of particular conditions, whether intentional or not.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.