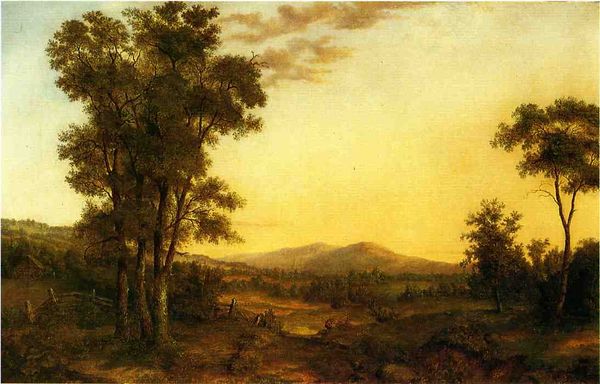

painting, plein-air, oil-paint

#

sky

#

painting

#

plein-air

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

rock

#

romanticism

#

mountain

Dimensions: 11.4 x 16.5 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: We are looking at Theodore Rousseau’s “Valley in the Auvergne,” painted around 1830. Rousseau, a key figure in the Barbizon school, captured this scene en plein air, utilizing oil paints. What’s your immediate reaction? Editor: It feels like a place holding its breath, you know? A quiet vastness, and the muted palette lends it a certain melancholic beauty. The painting seems to hint at larger questions. What’s beneath the surface of this landscape, beyond the visual serenity? Curator: It's fascinating you say that, given the historical context. The Barbizon school, and Rousseau in particular, championed a shift away from academic landscape painting. They moved outdoors, engaging directly with nature. "Valley in the Auvergne" exemplifies their commitment to portraying the French countryside not as an idealized backdrop but as a tangible space shaped by environmental factors and socio-economic ones, too. Editor: Precisely! Considering Rousseau's radical artistic approach, one must question the lack of human figures in the picture. How might this landscape relate to ideas of peasantry and labor? In the social and political climate of 1830s France, romanticizing the rural wasn't apolitical; it reinforced class and gender biases that privileged bourgeois subjects and erased marginalized experiences. What statements are these aesthetic and ideological codes making, then? Curator: An important consideration. While Rousseau wasn't overtly political in his art, his choice of subject matter certainly had implications. His commitment to depicting the ‘real’ French countryside was a deliberate move away from the grand historical narratives favoured by the establishment. And though populated by labourers, the Auvergne region would've carried significance given rural shifts following the revolution. Editor: The absence of clearly defined roads or paths heightens the effect; instead, a pale river leads the spectator’s eye deep into the composition’s background. As you note, Rousseau subtly guides our gaze into the folds and hollows of land while concurrently suggesting something beyond. It speaks to me as a site of both immense promise and profound, irrevocable loss—like our Earth itself. Curator: The subdued colours, predominantly browns, greens, and greys, further contribute to the sense of melancholy, but also offer incredible subtlety, if that makes sense. And despite that melancholy, the composition maintains a striking sense of balance, with the hills and sky in a near equilibrium. Editor: Yes, there’s a certain visual tension and an underlying struggle within those contrasts, with those sombre shades; ultimately it becomes quite an active composition. Thank you, this was very insightful. Curator: Indeed. Thinking about the work in its time definitely shapes our appreciation of it today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.