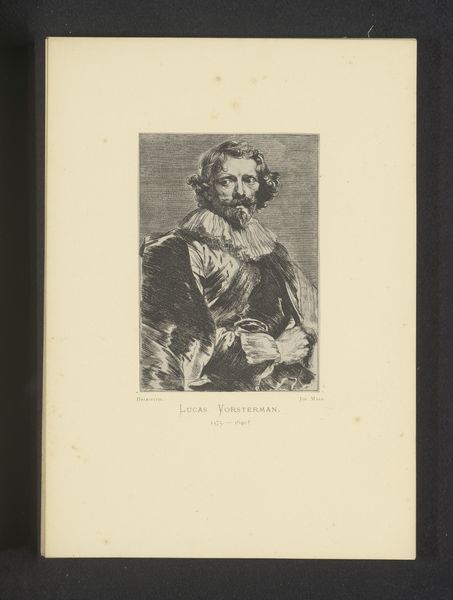

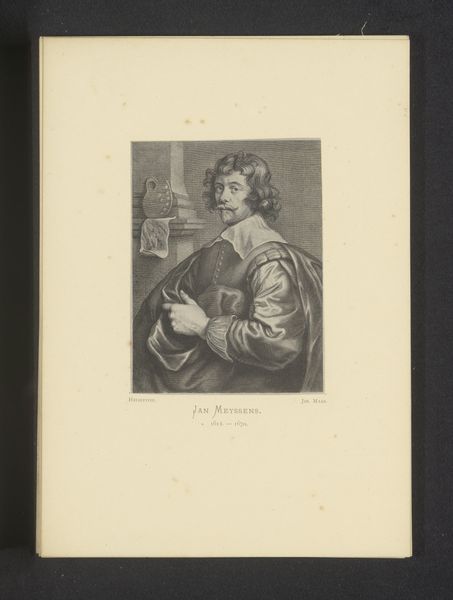

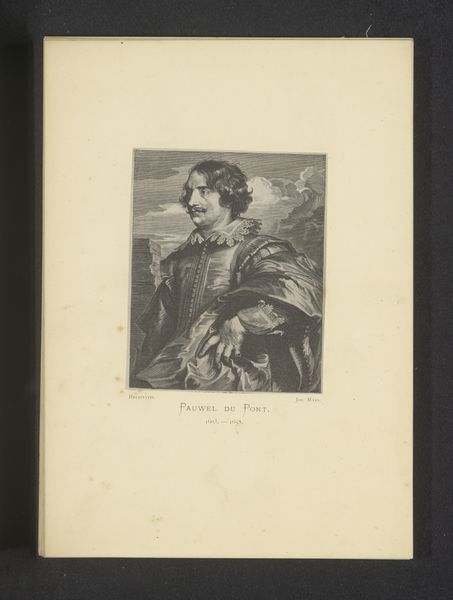

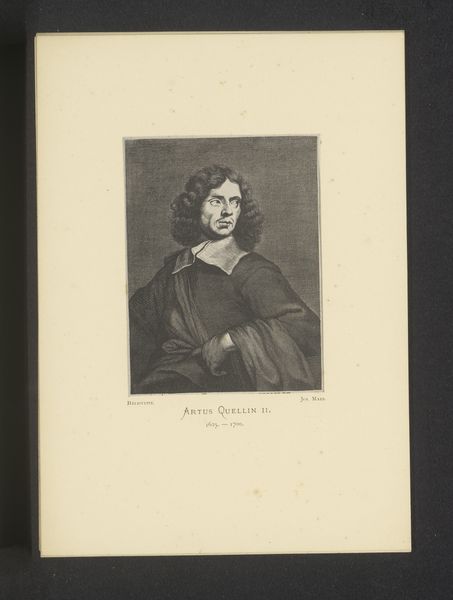

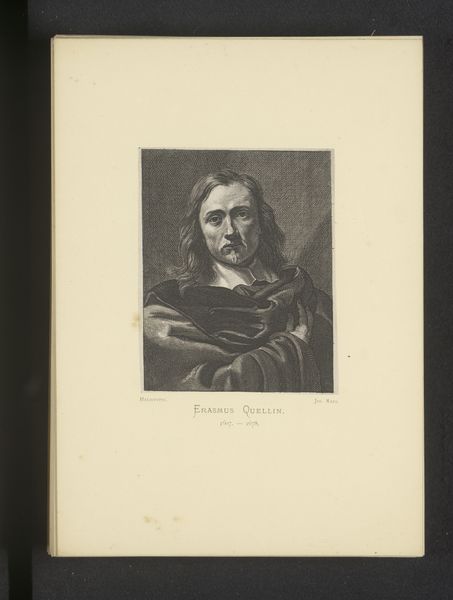

Reproductie van een gravure van een portret van Justus Sustermans door Anthony van Dyck before 1877

0:00

0:00

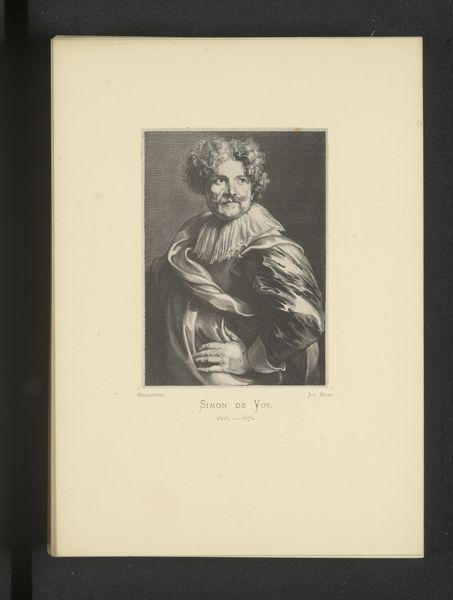

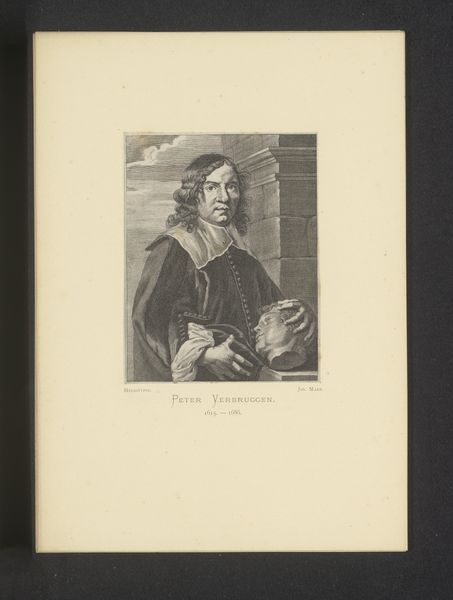

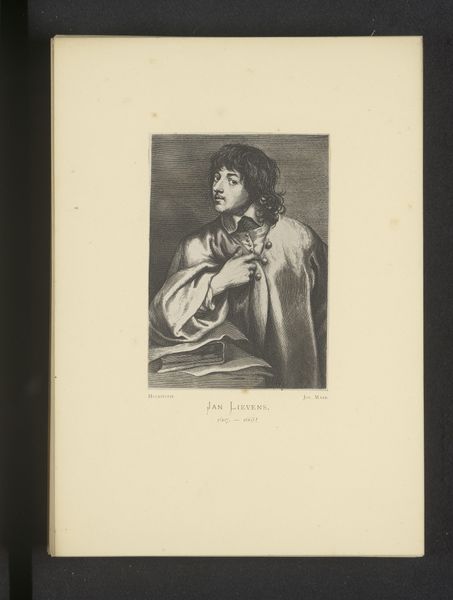

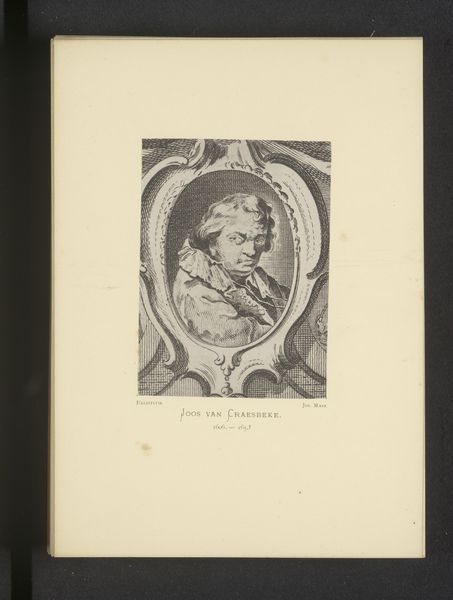

Dimensions: height 118 mm, width 89 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a reproduction of an engraving. It depicts a portrait of Justus Sustermans and was made by Anthony van Dyck. The print itself likely dates to before 1877. Editor: Hmm. Stark, isn't it? The high contrast and almost frenetic lines give it this intense, immediate feel. It's like looking into the subject's very soul. Almost unsettling. Curator: It’s fascinating how portrait engravings circulated images and ideas in the Baroque era, especially concerning status and intellectual achievement. Editor: Right. It was PR, Baroque style! Although there’s something vulnerable in the expression too. The flourish of the cloak is like a nervous flutter of energy. Is that just me? Curator: I see it, especially knowing that Van Dyck himself was incredibly influential. Prints like this elevated his sitters in the public imagination. They acted almost like modern celebrity endorsements. Editor: Interesting parallel. I wonder if Justus ever posed with a seventeenth-century version of a shampoo he used? It all goes back to image control. This controlled representation, that nervousness… were these people really like this? What secrets are those dark strokes trying to conceal? Curator: These kinds of images became tools within complex systems of patronage and influence. The circulation of images cemented alliances and established reputations beyond the court. Editor: So it’s not just about pretty pictures or capturing likenesses. It is about power. This isn't merely an image; it's an artifact of social ambition and projection. Curator: Absolutely. It reflects the mechanics of reputation-building in the early modern world. The baroque as a cultural marketing strategy, almost! Editor: Okay, I’m sold. It seems our slightly jittery friend here represents not just himself but an entire machinery of fame. What a thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.