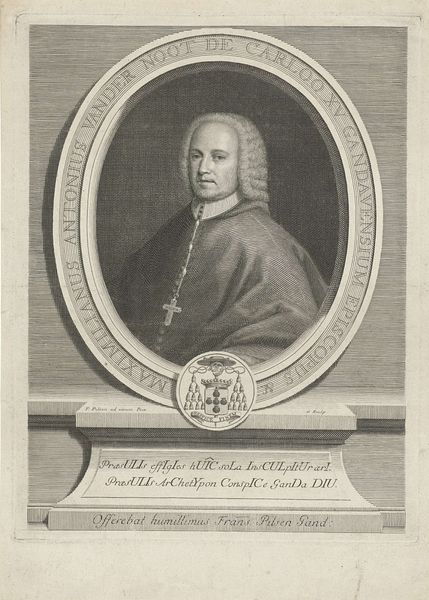

drawing, print, paper, pencil, chalk, black-chalk

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

charcoal art

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

chalk

#

water

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

black-chalk

Dimensions: 315 × 252 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

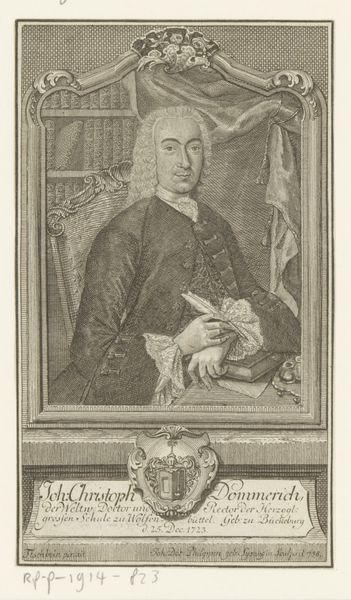

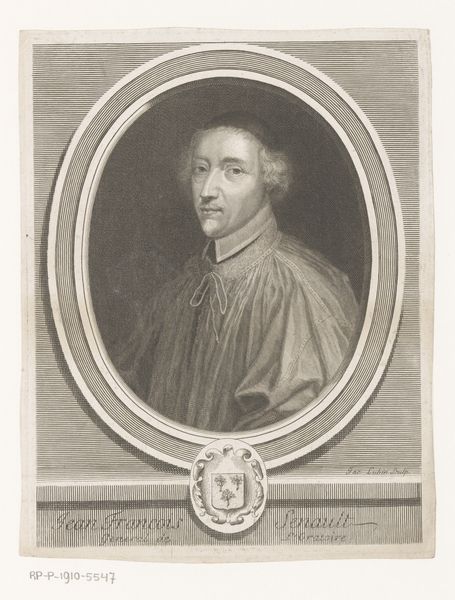

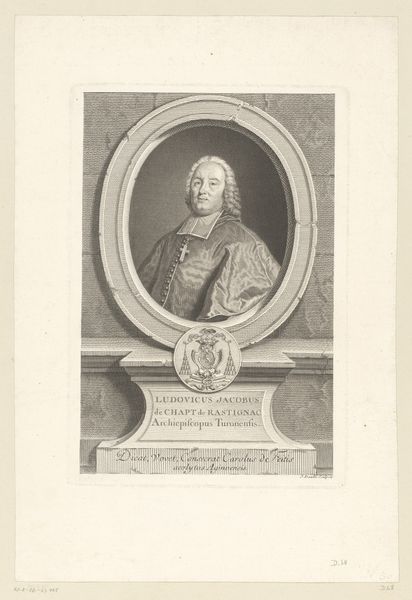

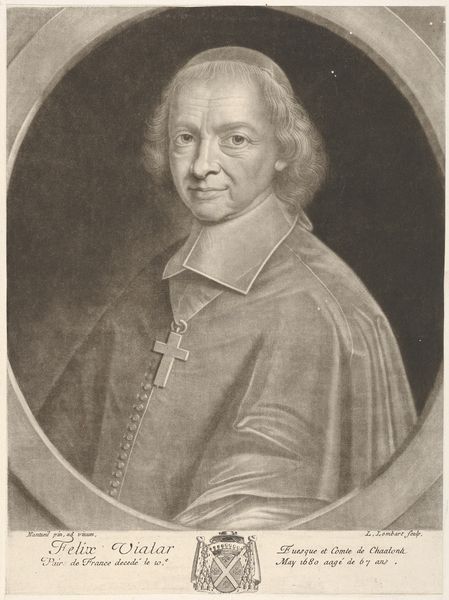

Editor: We're looking at "Portrait of Ecclesiastic," an undated drawing by Caspar Netscher, residing here at the Art Institute of Chicago. It's rendered in pencil and chalk on paper, giving it a rather subdued, almost solemn feel. What strikes me is the subject's gaze - direct, but… reserved. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Well, it's important to consider that in the 17th and 18th centuries, portraiture was a significant tool for establishing social standing. Depicting an ecclesiastic, Netscher navigates a complex network of religious and political power. His tools—paper, pencil, chalk—are relatively accessible. Do you think that accessibility challenges or reinforces the sitter's status? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn’t considered that the medium itself could be making a statement. Maybe the softness of the chalk democratizes the image somewhat? Does the presence of religious objects like the crucifix play into that public role? Curator: Precisely. Consider where this portrait may have been displayed - perhaps within the church itself, or even reproduced as prints for wider circulation. The crucifix becomes less about personal devotion and more about public performance of piety and authority, cementing the Church’s power and reminding people of the politics of belief. Editor: So the portrait acts almost like a form of propaganda? It’s less about capturing an individual likeness and more about reinforcing institutional power? Curator: It's a nuanced form of visual messaging. We must ask: who commissioned the work and what purpose was it to serve? Consider the control over the images allowed institutions like the church to perpetuate certain narratives. The slight melancholy we initially observed could also be read as calculated, designed to evoke empathy and respect for the church. Editor: That shifts my perspective quite a bit! I was focusing on the individual, but now I see how the piece serves a much larger cultural purpose. Curator: And that’s precisely where art history bridges aesthetics with critical social observation, making even a seemingly simple portrait a fascinating reflection of its time. Editor: I’ll definitely be looking at portraits differently from now on. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.