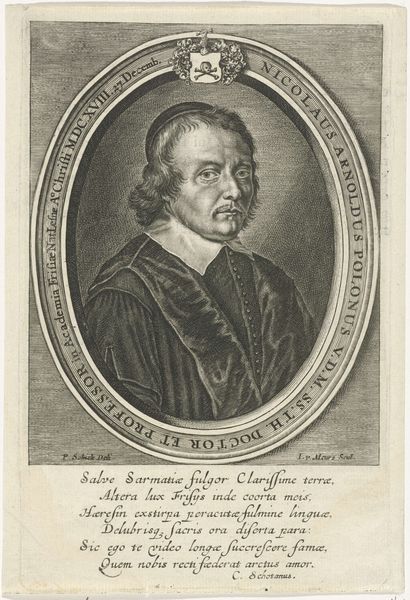

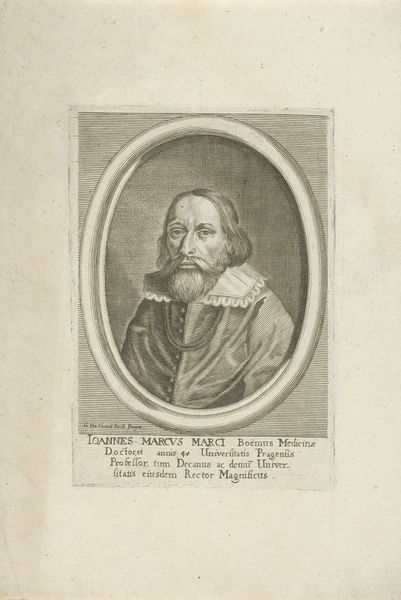

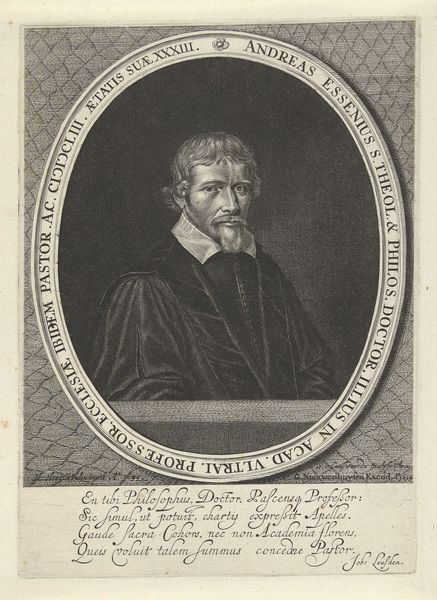

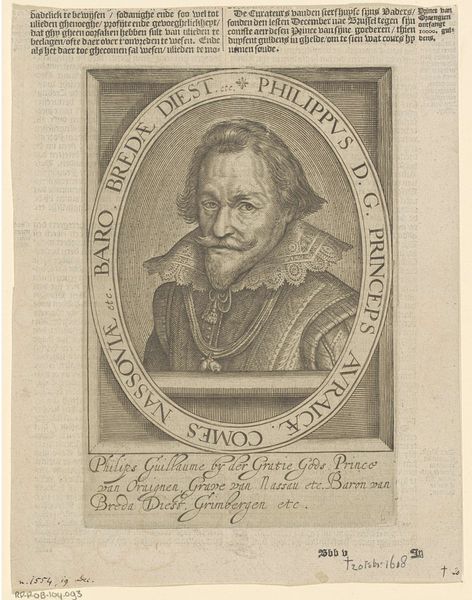

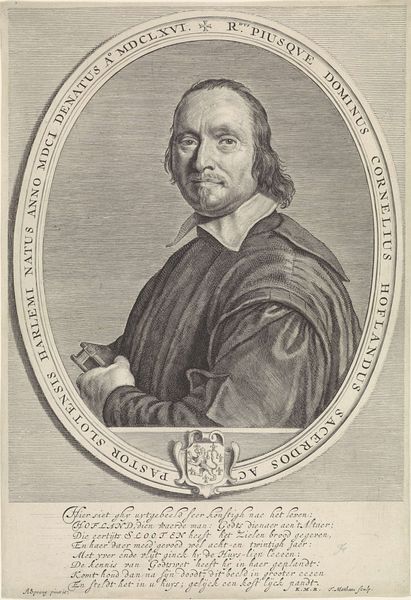

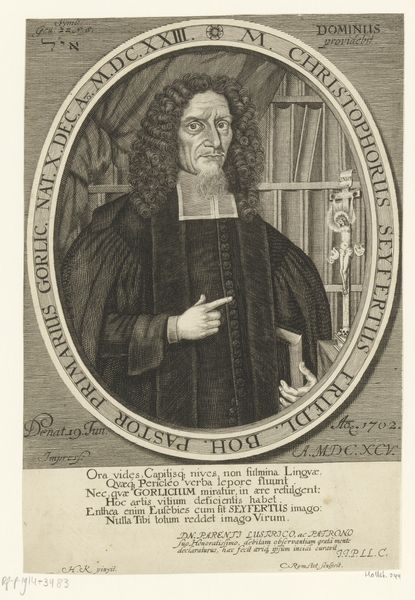

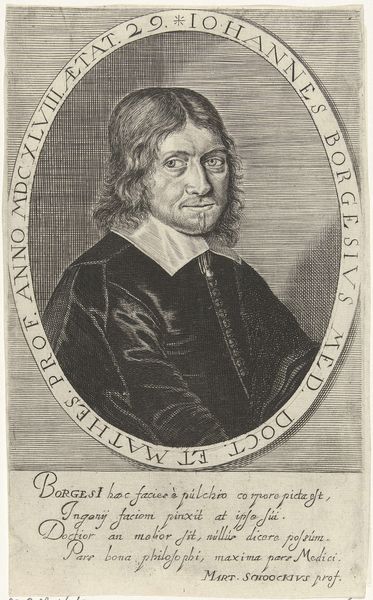

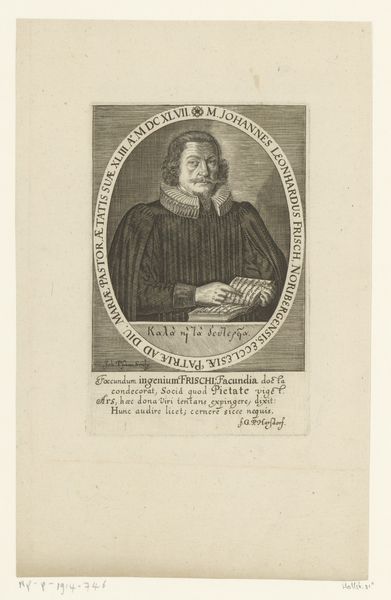

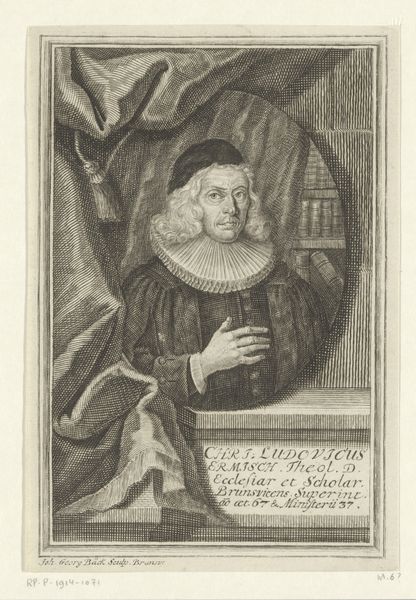

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 203 mm, width 149 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We’re standing before a work by Romeyn de Hooghe: it’s a portrait of Matthijs Balen, dating back to 1677. It's an engraving. What's your first impression? Editor: I see tremendous labor; all those delicate lines! It gives the subject, Balen, a stern but somehow softened quality. There’s this amazing tension between precision and fluidity that really makes me think about how material impacts content. Curator: I feel it. The engraving medium seems fitting given the historical importance associated with Balen. It speaks to both the physical act of image creation and also nods to permanence, wouldn’t you agree? Editor: Absolutely! Engravings, and printed matter generally, in the Dutch Golden Age speak to broader societal shifts, to increasingly literate and commercially engaged public audiences who want to be remembered. Curator: It really places Balen within a specific time and space, doesn't it? He holds a book –presumably his history of Dordrecht–, there's a bookshelf looming from the left side, and there is the barest whisper of a city scene visible through the window. He's framed as learned, and also connected directly to the urban sphere around him. Editor: Yes, and if we think of the social history of printmaking, De Hooghe's image brings Balen's historical account to a broader, more accessible audience. It elevates not only Balen himself, but also this whole emerging culture of accessible printed knowledge. I can imagine a wealthy merchant owning this portrait of Balen in the form of a print. It could then be re-engraved and circulated, reproduced into ubiquity. Curator: You are definitely highlighting something crucial – the way value is generated through circulation, through multiplying an image and message. What remains is this sense of accessibility married to an image of lasting substance. It does seem fitting somehow, that in the very act of depicting the historian, de Hooghe is participating in and shaping that history. Editor: And that kind of engagement is still felt even now, centuries later. What does that say about its enduring value, its continued relevance to today?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.