carving, relief, photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

photo of handprinted image

#

carving

#

sculpture

#

relief

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

carved into stone

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

architecture

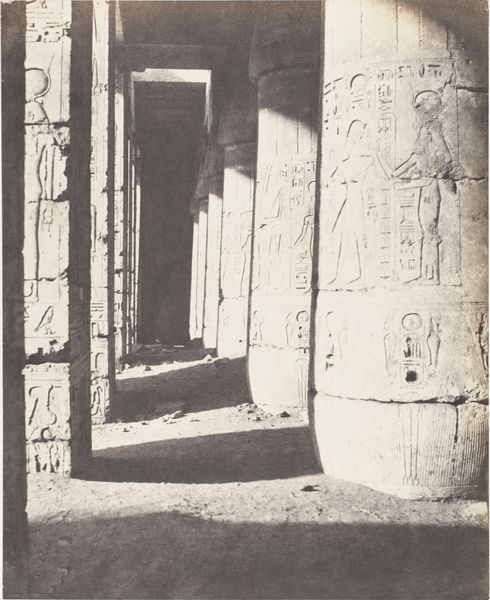

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 163 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

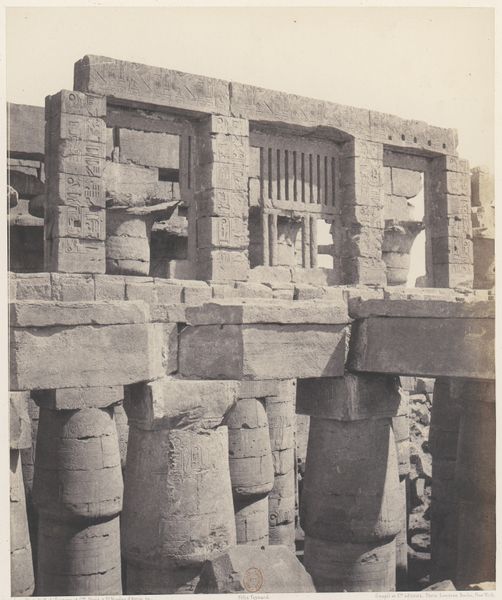

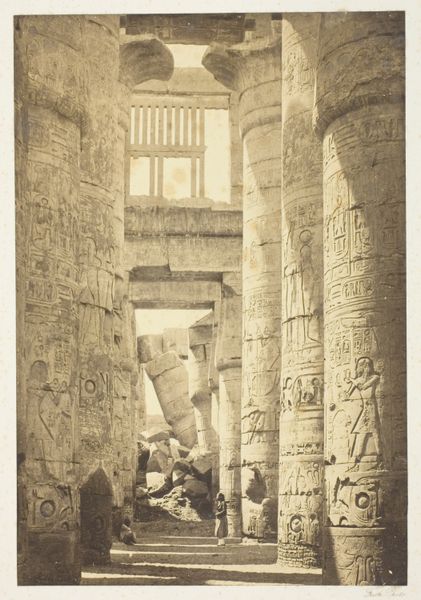

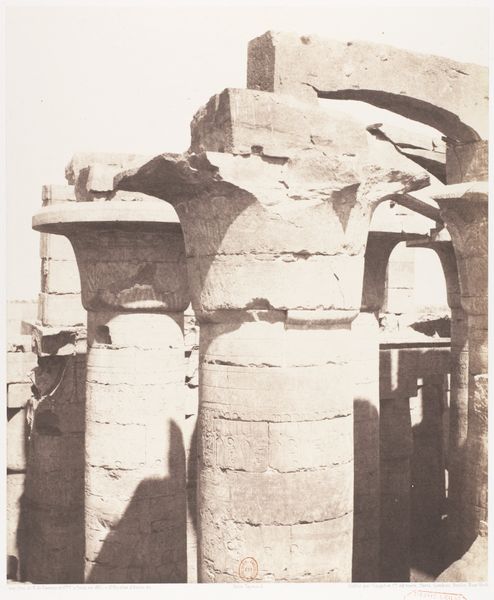

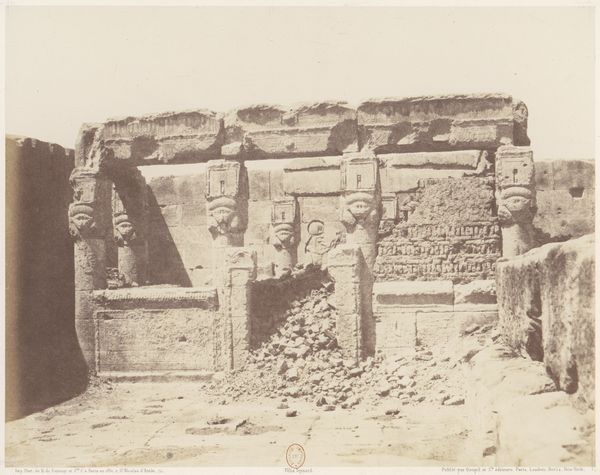

Curator: Look at this gelatin silver print from before 1862, titled "Doorgang in het tempelcomplex van Medinet Haboe." It’s the work of Francis Frith, and it’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It feels so incredibly weighty. The sheer density of the stone and those imposing hieroglyphs give a real sense of enduring power. The monochrome also brings this palpable feel to the image. Curator: Absolutely. Frith has captured more than just the architecture; he’s documented a fragment of a civilization. Those carvings… the narratives, the rituals they embody – they speak of a complex society that saw the world through a vastly different symbolic lens. Editor: And seeing it through Frith’s lens raises interesting questions about the Western gaze on Egypt in the 19th century. How complicit was early photography in exoticizing and appropriating ancient cultures? We must think about colonialism. This isn't just a picture of a ruin. It’s a record of cultural interaction and possibly of an imbalance of power. Curator: That's a critical point. But even within that context, I can’t help but feel a sense of wonder at the repetition of forms. Consider how particular shapes, repeated and standardized, act as vessels for deeply encoded concepts and values of Ancient Egypt. We can find the continuity through visual culture in Ancient Egypt, but only from this representation through an image, and only when filtered through Frith’s work and gaze. Editor: Wonder, but also responsibility. We need to acknowledge how access to these images has been unequally distributed and how the stories told about them have often served very specific ideological interests. We can’t let our awe blind us to that history of exploitation. Who owned the ability to document these cultures? And how was that power used? Curator: It is powerful to see how this photograph holds cultural memory across millennia – reminding us both of humanity’s ability to create enduring forms and the responsibility we share in interpreting them thoughtfully and critically. Editor: Indeed. And that dialogue between aesthetics, ethics, and historical awareness is, perhaps, the most enduring impression left by Frith's photograph.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.