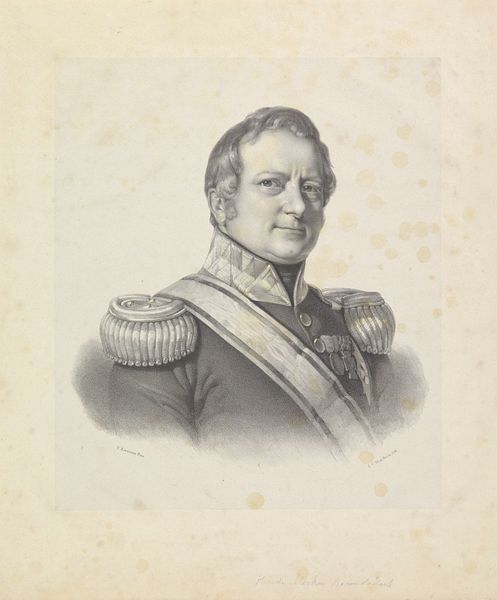

Portret van Anthonie Willem Hendrik Nolthenius De Man 1818 - 1863

0:00

0:00

isaaccorneliselinksterk

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, pencil, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

historical photography

#

pencil

#

19th century

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 460 mm, width 360 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this portrait, I am immediately struck by its almost photographic realism, achieved solely with pencil and engraving techniques. It gives it a certain mechanical and reproductive quality that I find incredibly compelling. Editor: I see him as a symbol of 19th-century masculinity and power, with its inherent complications. It’s a study in status, frozen in time, yet also speaks volumes about class, access and representation. This portrait, identified as “Portret van Anthonie Willem Hendrik Nolthenius De Man," dates sometime between 1818 and 1863. Curator: The rendering of his military uniform – the buttons, the epaulettes – must have taken considerable time and skill. The material qualities of pencil on paper combined with engraving allows for subtle gradations of light and shadow. We also have to ask who was accessing those skills and that level of education? Editor: That's a crucial point. Portraits such as these served as instruments of power. The ability to commission art and preserve one's image was decidedly the privilege of a wealthy class. Considering that it is held at the Rijksmuseum, how do we decolonize this image and see beyond this man? What responsibility can an institution take on to address representation? Curator: Precisely, we need to consider the socio-economic circumstances and power structures inherent in portraiture. I’m looking closely at the engraved lines, almost imagining the artisan's labor and tools to make a mechanical process still imbued with immense effort. How does our understanding of materiality connect us to the past, allowing for deeper analysis of history from multiple viewpoints? Editor: Absolutely. How might it alter our approach to history if, rather than celebrating, we chose instead to view art's role in upholding power and perpetuating injustice? Curator: It asks the important question of whose labor and skill are valued or discarded by institutions or history? Even within portraits, the making shows hierarchies and labor divides between artisan, engraver and painter that go unacknowledged in most displays and readings of artwork like this portrait. Editor: By revealing the social contexts of creation we enable viewers to engage in crucial dialogue concerning equity and agency as opposed to a superficial admiration. Ultimately, analyzing traditional art via these pathways is necessary to comprehend it with a greater appreciation for depth of awareness.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.