print, engraving

#

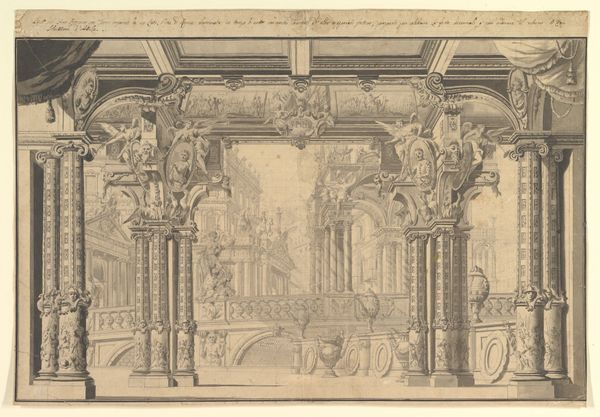

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

geometric

#

line

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 121 mm, width 103 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The engraving we're viewing, titled "Gezicht op een antiek gebouw met fontein" by Johann Oswald Harms, completed in 1673, presents us with a vision of architectural fantasy. What’s your first reaction to it? Editor: It’s…melancholic, isn’t it? Despite the classical grandeur, there's a sense of decay, a suggestion of time's passage eroding even these supposedly eternal structures. It is quite sobering. Curator: Indeed. Harms, deeply entrenched in the artistic milieu of the Dutch Golden Age, engaged heavily with depicting classical themes. What appears like simple architectural representation belies a wider investigation into themes of power and legacy. Think of what Harms communicates when pairing the city's idealized rendering alongside crumbling structures that are slowly consumed by their immediate environments. Editor: So, you’re seeing that tension too! It’s interesting how he plays with light and shadow, heightening the sense of drama but also this feeling of something being…over. We're viewing ruins—a meditation on time and loss within a cityscape, almost like an historical omen that looms like a dark shadow overhead. Curator: Exactly! And consider the very medium of engraving itself—a technology allowing for mass dissemination of images. Harms’ vision, thus, entered countless collections, shaping perceptions of antiquity. The print, by its nature, allows us to democratize these visions and examine power and society through different perspectives. It becomes something we can analyze collectively as it transcends space and time. Editor: Thinking about accessibility, what does it mean to circulate an image of European dominance rendered in a 'classical' style to audiences undergoing colonial subjugation? In what ways does this particular engraving propagate the ideals of that superiority at the precise time such notions are undergoing public critique? Curator: That's a crucial point, raising important ethical questions regarding whose history is privileged, how historical power is preserved and framed, and how audiences are impacted, even today. It requires constant engagement with context to decode what Harms is trying to communicate and our role in interpreting the imagery ourselves. Editor: This small print is more than a pretty picture; it forces us to interrogate history and art and consider the implications of sharing stories that continue to carry the legacies of power. Curator: Absolutely. Its layered commentary ensures its relevance centuries later. I wonder, how else might future audiences decode and contextualize this piece? Only time will tell, it seems.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.