Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

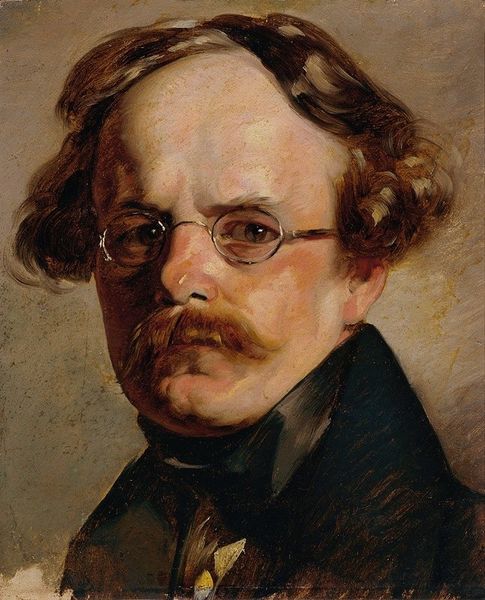

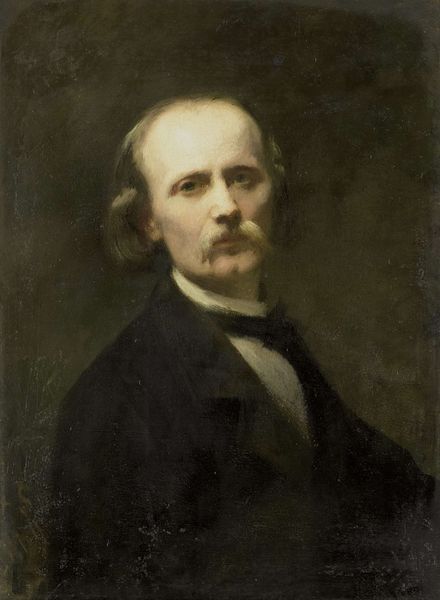

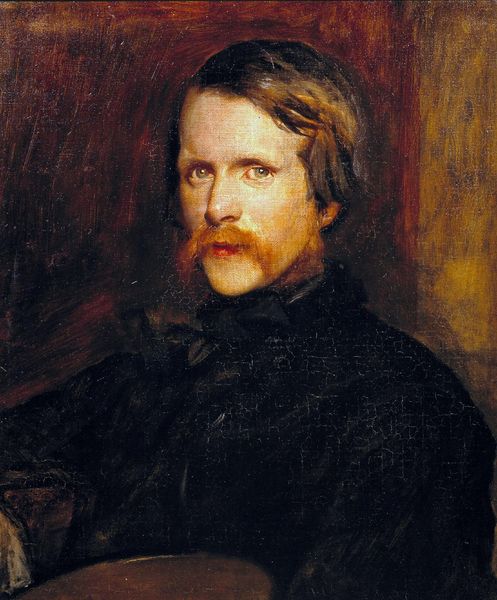

Editor: This is Arnold Böcklin's "Portrait of Professor Fritz Burckhardt-Brenner," created in 1868 with oil paint. The muted color palette lends the professor a somber, almost serious demeanor. What catches your eye? Curator: I notice how the materiality of the oil paint serves not just to represent, but to *embody* Burckhardt-Brenner’s social standing. Think about the pigment itself: Where did the materials to create the paints come from? Who mined them? And how does the very act of Böcklin transforming those raw materials into a portrait elevate both the sitter and the art form? Editor: That's a great point. It's easy to overlook the labor involved. But did commissioning a portrait solidify social hierarchies? Curator: Precisely. This portrait, born from specific materials and human effort, became a commodity—a status symbol of bourgeois culture. It's not just a picture; it’s evidence of social and economic dynamics at play. What do you notice about his clothing and the background, then? Editor: His dark jacket and tie against that very dark background feels…intentional. Almost manufactured? To emphasize his intellectualism? Curator: Absolutely. Notice the dark colour and tailored clothing—the *textile* and how this creates a contrast to skin, implying a separation between body and societal roles. These are *constructed* images. Editor: This shifts my thinking of portraits of just capturing a likeness into seeing the social context it’s coming from and participating in. Thanks! Curator: And consider what these portraits consume. They utilize time, skills, raw materials to display power structures as art and as possession, shaping perception and status. A good point to always think of.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.