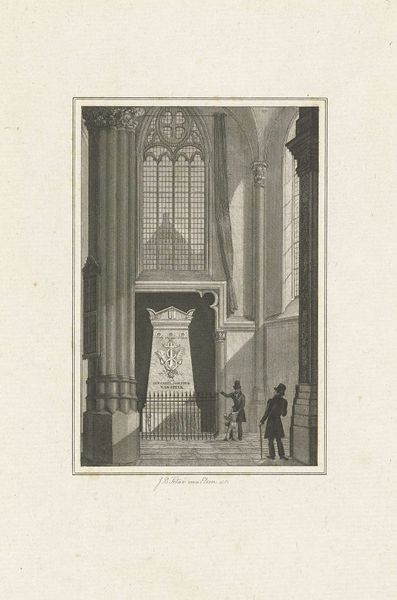

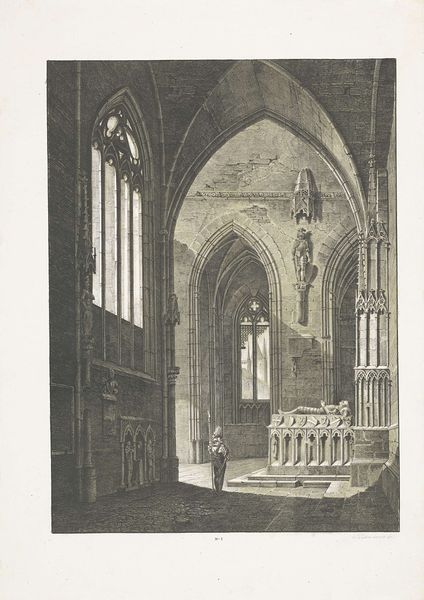

Praalgraaf van Willem I van Oranje in de Nieuwe Kerk te Delft 1751 - 1822

0:00

0:00

noachvanderiimeer

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving, architecture

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 246 mm, width 207 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

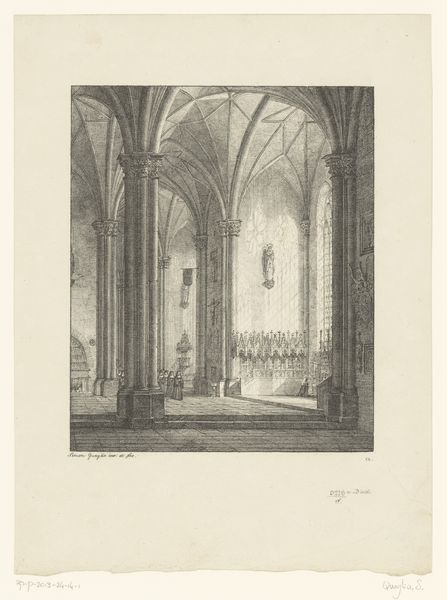

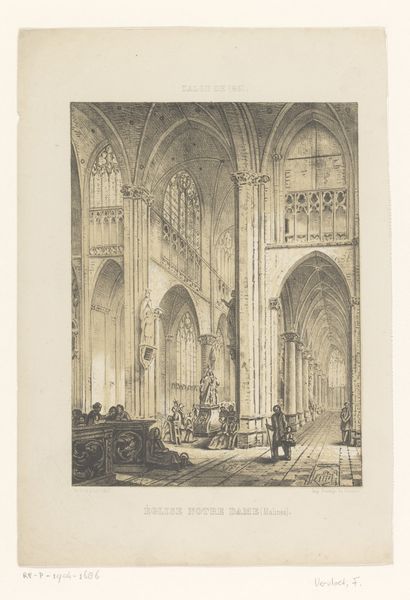

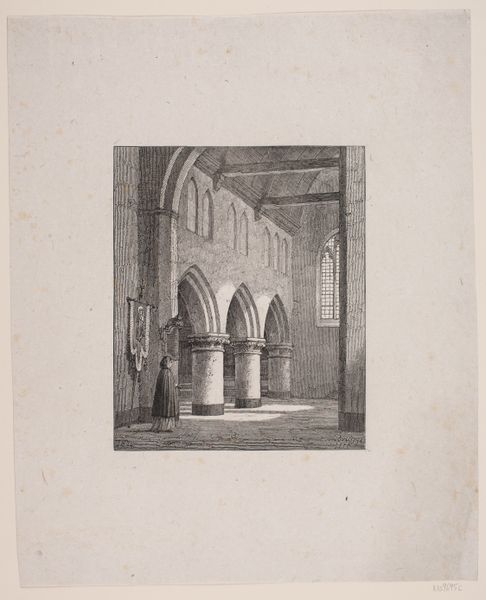

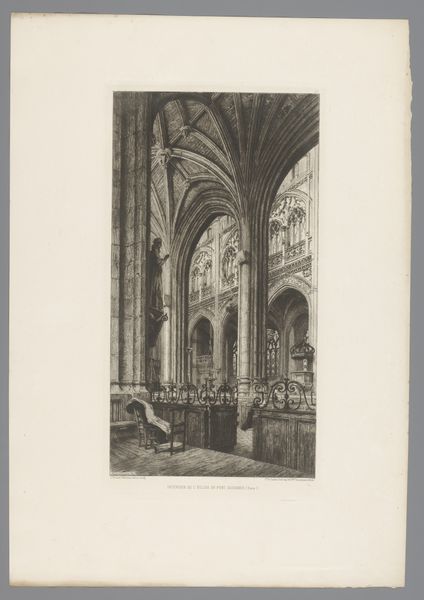

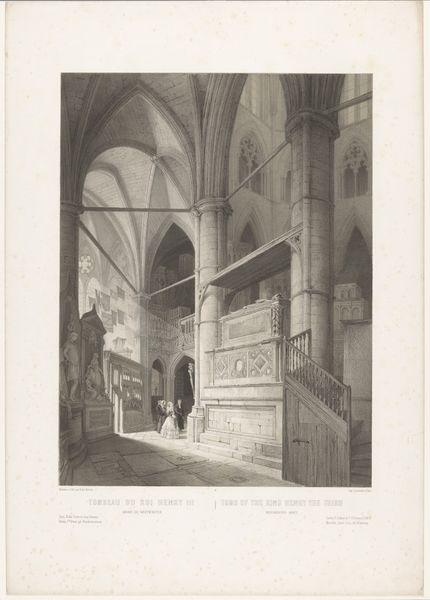

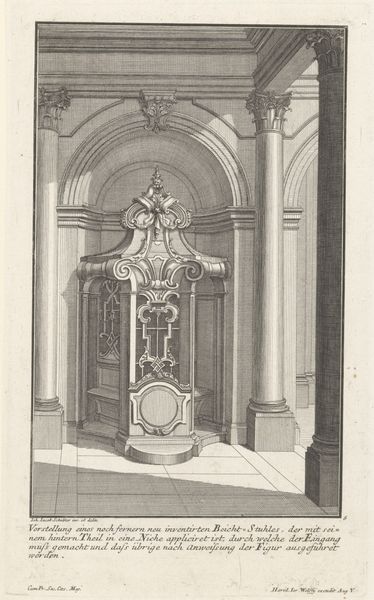

Curator: Welcome. Today, we're looking at Noach van der Meer (II)'s print, "Praalgraaf van Willem I van Oranje in de Nieuwe Kerk te Delft," created between 1751 and 1822 and held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: Immediately striking is the play of light—the columns emerge boldly through masterful shading that divides the space with remarkable contrasts. A contemplative, quiet mood fills the architectural scene. Curator: Indeed. Note how van der Meer employs engraving techniques to articulate not just light, but also architectural mass and depth. Consider the cross-hatching—especially evident on the columns and arches—which adds layers of tonality and texture. This emphasizes the cathedral's interior volume. Editor: For me, what grabs attention is how the architecture dwarfs the human figures. A man, possibly a caretaker, stands to the side, and this very relationship accentuates the tomb’s grandeur, suggesting a hierarchy—labor and observer beneath national symbols. The materials evoke stonecutters and guild members’ involvement—a collaborative craft of historical importance, with national hero's remains enshrined in stone and craftsmanship. Curator: Quite perceptive! Van der Meer expertly arranges space, employing strong diagonals from foreground to background, further emphasizing scale. The eye is thus guided inward, navigating rows of columns, past funerary banners, finally to what lies beyond… a carefully planned perspectival view. Editor: Let’s also look at how this print replicates an actual, monumental object. We have a depiction of the tomb meant to symbolize more than the man, it is representing Dutch identity itself! It raises questions of labor involved. From the mining of materials to skilled masons who would’ve designed and built, everyone has worked to preserve this moment for public viewing. The print merely allows for circulation. Curator: Yes. The image's visual clarity—the linear precision of the architectural details—offers clarity and rational structure, embodying Dutch Golden Age ideals about order and civic virtue. A carefully constructed symbol meant to express state ideals through aesthetic form. Editor: Absolutely. And understanding how those aesthetic choices echo material and political conditions gives us so much insight, right? Curator: It does indeed! This piece elegantly shows the dialogue between form and function… each informing our understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.