Dimensions: height 245 mm, width 158 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

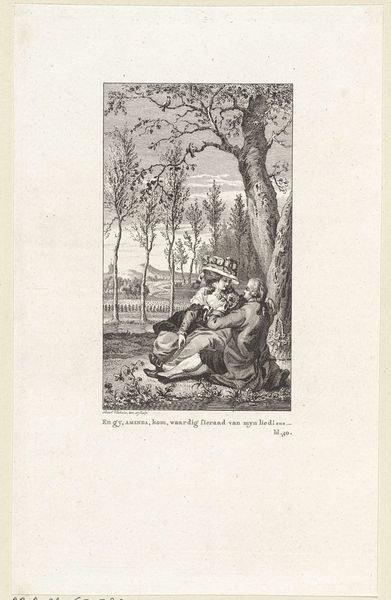

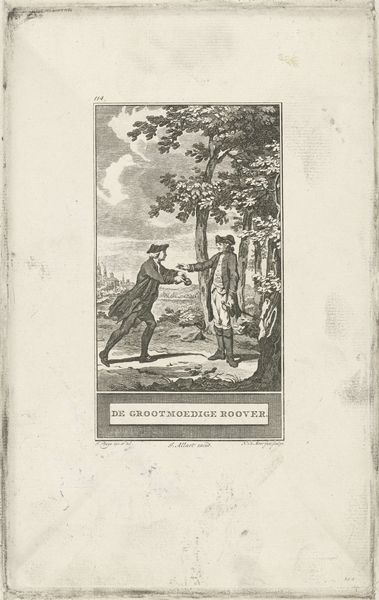

Curator: This charming print is entitled "Nachtegaal en de koekoek," or "Nightingale and the Cuckoo," created between 1778 and 1785 by Noach van der Meer II. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It strikes me as incredibly picturesque, like a scene lifted directly from a sentimental novel. The composition is quite theatrical, almost staged. Curator: It’s fascinating how van der Meer translates genre painting into printmaking. We see a carefully crafted image—the lines, the shading created through hatching and cross-hatching—a conscious attempt to replicate the effect of painting. What is also interesting is the context: prints at the time served as an effective tool for the circulation of visual narratives, impacting not only the fine arts but book illustration. Editor: I find myself drawn to the couple in the foreground, seemingly lost in their own world within the deeper forest. They're undeniably the focus, placed strategically against that densely engraved woodland backdrop. Notice the woman is pointing to what is supposedly a nightingale. It definitely reads to me as this almost idyllic, pastoral scene—but there’s an artificiality, which is enhanced through this being a reproduced image and therefore destined for a widespread public. Curator: Right, the staged feeling is very much of its time, tapping into Romantic ideals through this landscape. Look closer though, you see another pair behind the highlighted couple – are they simply further into the forest or lurking, perhaps? Van der Meer creates something more complicated in the print’s narrative than first impressions suggest. The means of production of such an image speaks directly to how Romanticism played a key role in marketing both idealized rural settings as well as more unsettling ideas to wider audiences. Editor: And the way this very common narrative is etched into copper plates - this medium allows for infinite reproduction and dispersal of the image throughout Dutch society. From a craft-history perspective, each pull would likely require intense manual labor by various skilled printers. The contrast between this highly-automated print work for the public and the image of tranquil rural life the work conveys is rather profound. Curator: Exactly, thinking about its place in social and material history really complicates the seemingly straightforward narrative here. We’re invited to see how cultural production isn't just aesthetic expression but labor, and social messaging, as well. Editor: Absolutely, looking closely reveals just how deeply intertwined material and social factors were within art creation during that time period.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.