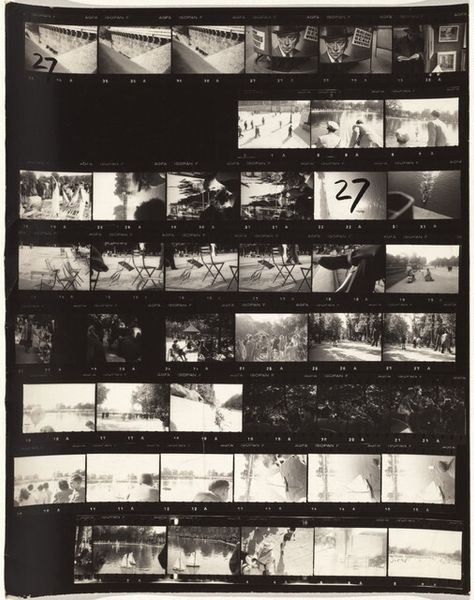

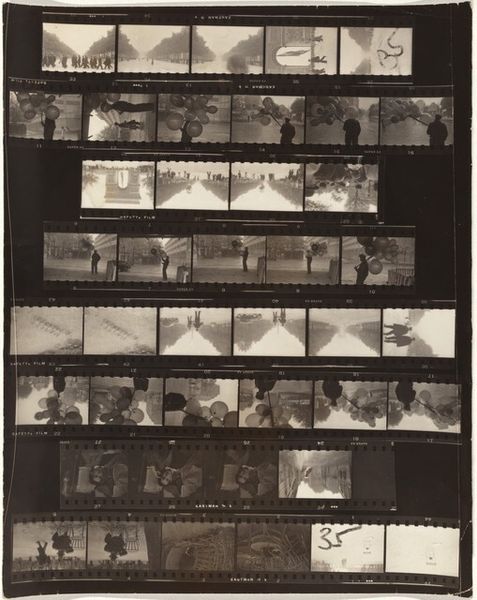

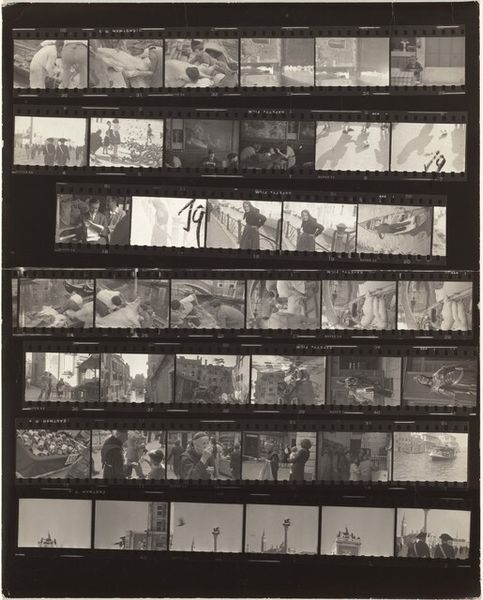

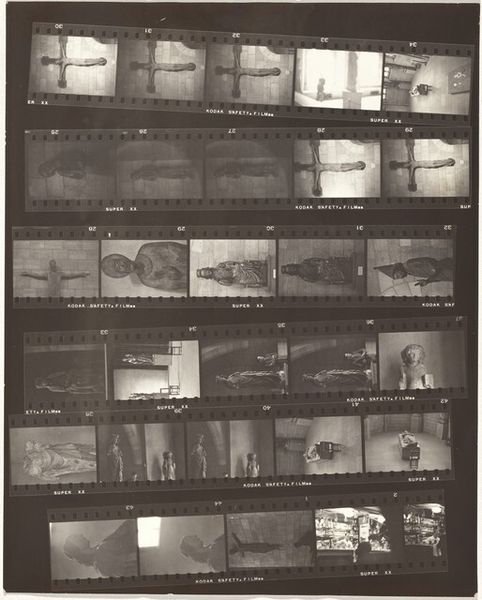

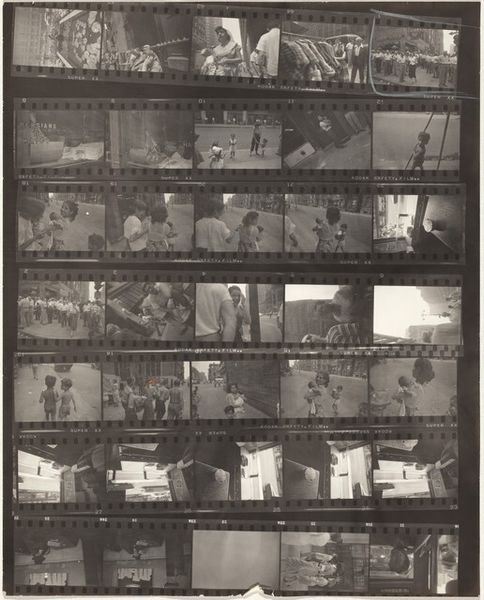

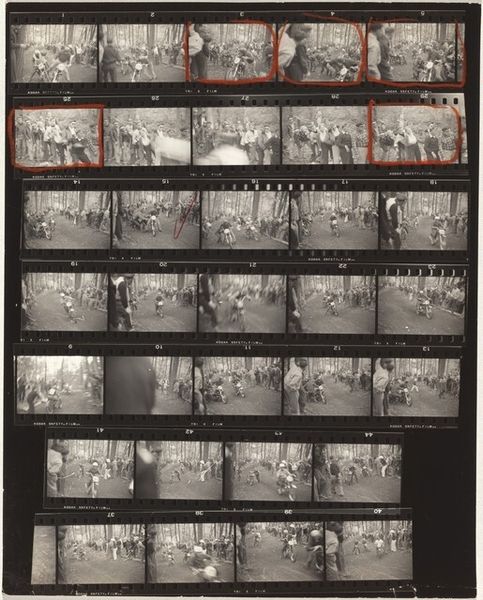

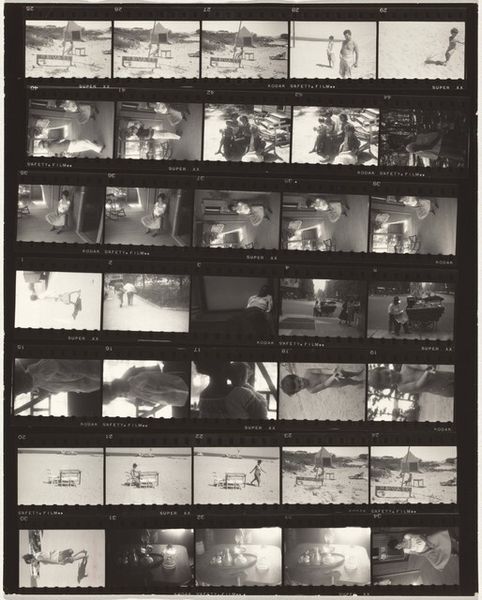

Dimensions: overall: 29.8 x 23.8 cm (11 3/4 x 9 3/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

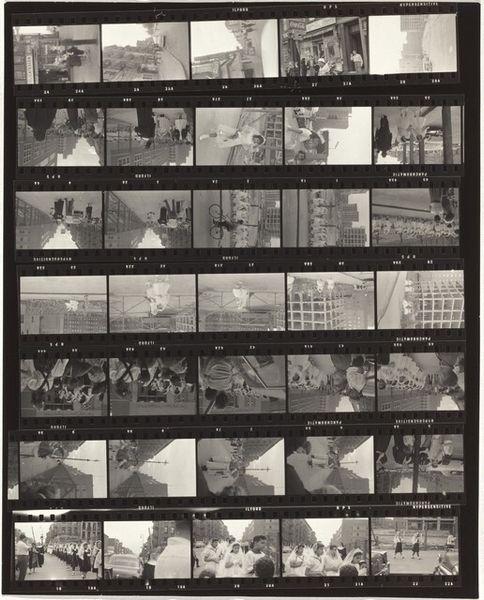

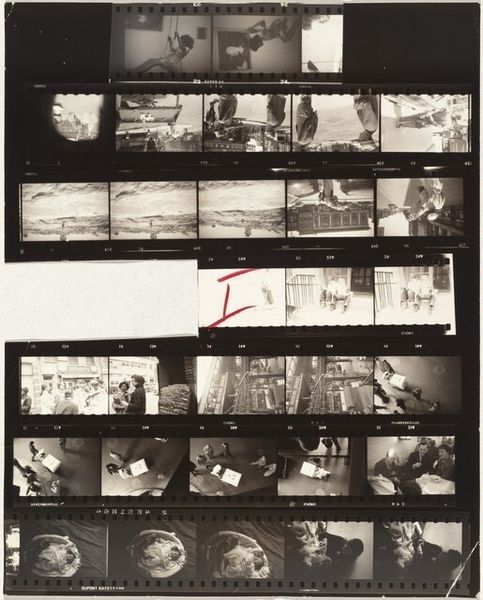

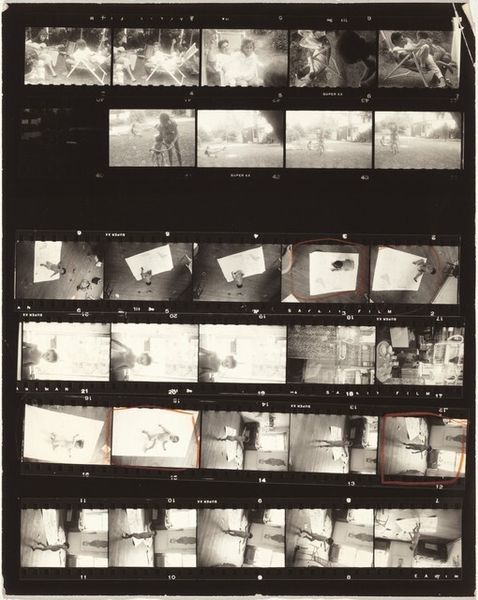

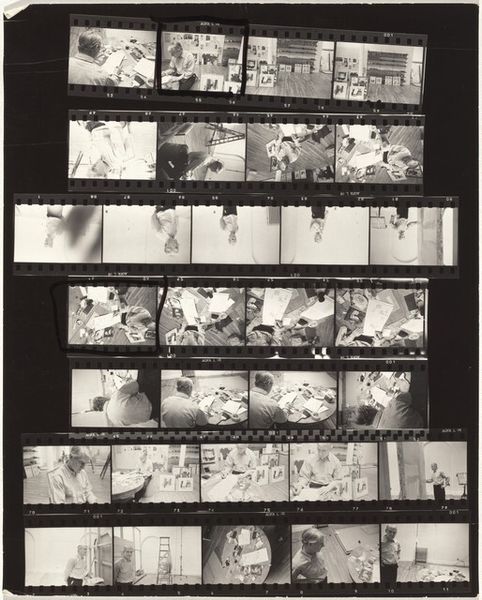

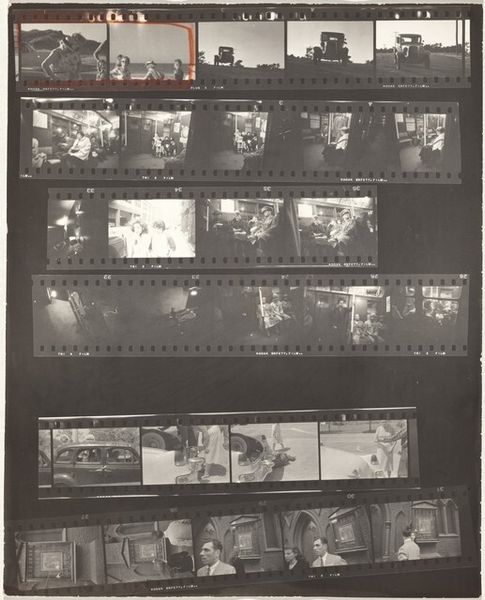

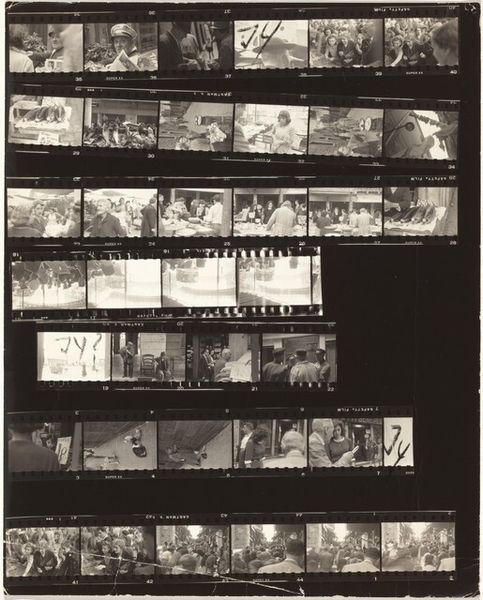

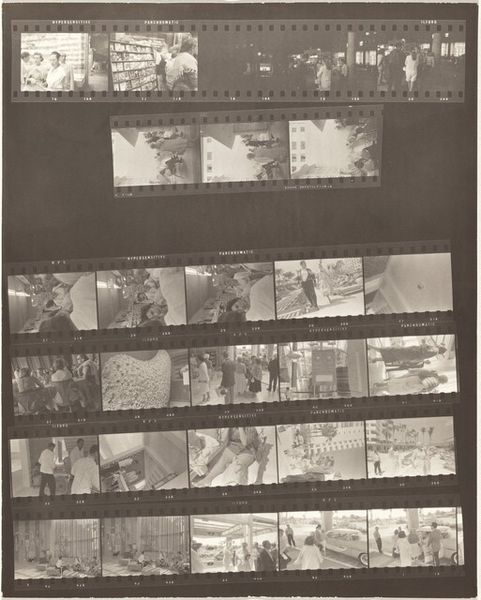

Editor: So this is Robert Frank's "Paris 18A," a gelatin-silver print from around 1949-1950. It shows multiple strips of a contact sheet. It feels fragmented, like glimpses into fleeting moments. How do you interpret this work? Curator: The contact sheet format is really key here. Frank isn’t presenting a singular, perfected image. Instead, he's showing us the process, the multiple takes, and the choices he made as a photographer. In the post-war period, this challenged the conventional ideas of photographic art and shifted away from formally posed, picture-perfect photography that you might see glorified by institutions. Editor: I see. It's almost like a behind-the-scenes look at his artistic process, and by extension a subversion of what's accepted in art. Why choose to show all the "failures" instead of only one "perfect" frame? Curator: Exactly! Think about the societal context. There was a desire for authenticity, for breaking down the artifice that perhaps characterized pre-war society. Street photography itself becomes a powerful tool to engage with the world. Would you say the photograph as a tool of truth had particular resonance following the exposure of the concentration camps? Editor: Absolutely. That makes total sense. I see how this "snapshot aesthetic" makes it accessible and even pushes a democratization of photography. Curator: Precisely! The visual language of the streets becomes its own form of cultural commentary, and the way a photograph enters a collection – such as in a book rather than in a gallery - can expand who gets to engage with art and how it is engaged with. Editor: I never considered how the presentation could influence the message. That's given me a lot to think about. Thank you! Curator: And for me too; this helps highlight Frank's own subversive commentary as the establishment adopts his innovations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.