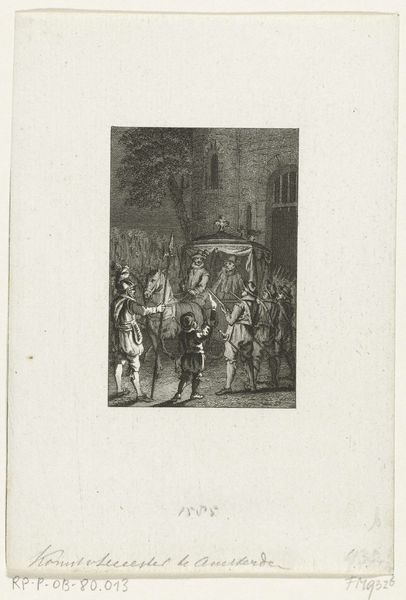

print, engraving

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

orientalism

#

line

#

sketchbook drawing

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 248 mm, width 151 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

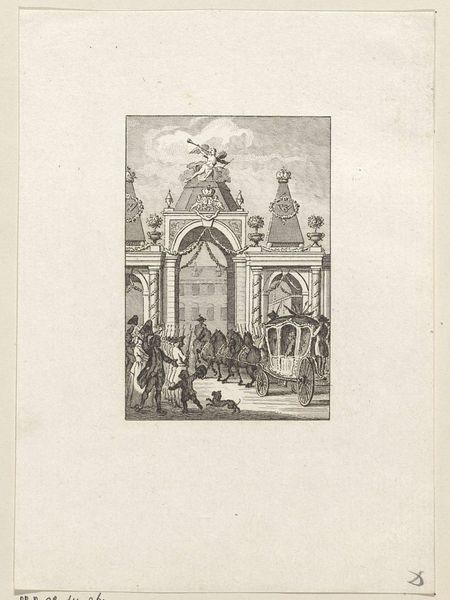

Curator: This engraving, attributed to Johannes Alexander Rudolf Best and titled "Koning in open rijtuig in oosterse stad," dates roughly between 1807 and 1855. The work is evocative. My initial impression is of an ordered chaos, a bustling scene rendered with surprising clarity despite the age of the print. Editor: A king in an open carriage in an Eastern city indeed. But what are we really looking at here? Beyond the immediate visual, the image invokes power structures, colonial gazes, and the performance of rulership against the backdrop of the ‘Orient.’ The engraving style itself plays into the romanticism of the exotic other. Curator: Agreed. The detail in the engraving process—the lines creating texture, light, and shadow—is meticulous. Look at the architecture; there's a fascination with replicating ornamentation. We see the physical labor inherent in reproducing not only the scene, but the orientalist fantasy. Editor: And whose labor are we really talking about here? It's crucial to consider Best’s historical context—what drove the interest in depicting these "Eastern" settings? Were these representations about genuine cultural exchange, or rather about reinforcing Europe's sense of dominance? Who was this work for and what did it mean to them? Curator: Undoubtedly, there's a problematic lens at play. The materiality of the print—the paper, the ink—connects it directly to a network of production and consumption. These images were commodities; tokens of a worldview actively being constructed and traded. Editor: The image operates as more than just a visual document. It's a complex artifact reflecting power dynamics. The gaze inherent in the orientalist style carries weight. How can we, today, deconstruct that and engage in conversations around representation, appropriation, and respect? The cityscape presented is frozen and passive, existing only as background for a European fantasy of rule. Curator: A fascinating consideration of power in this small engraving. I'm left pondering the weight these seemingly delicate prints carried in their time. Editor: Absolutely. It is a conversation we must continue, interrogating art's role in shaping perceptions, then and now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.