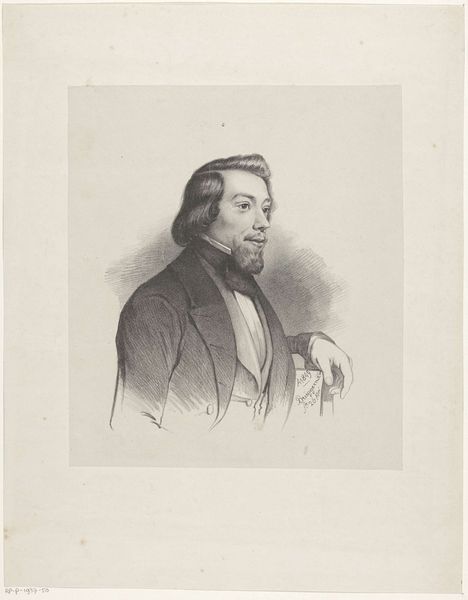

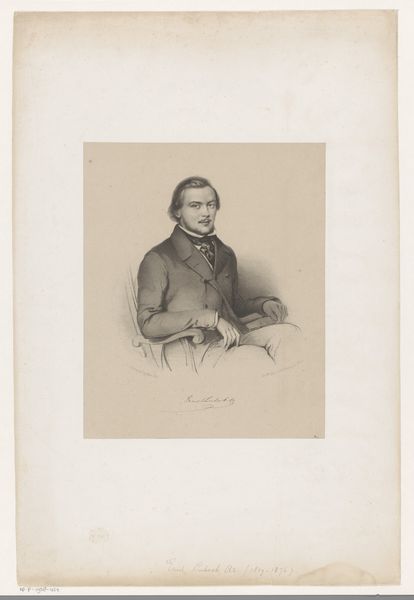

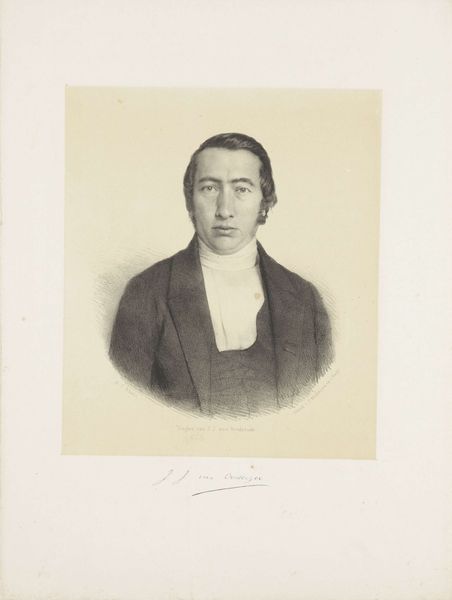

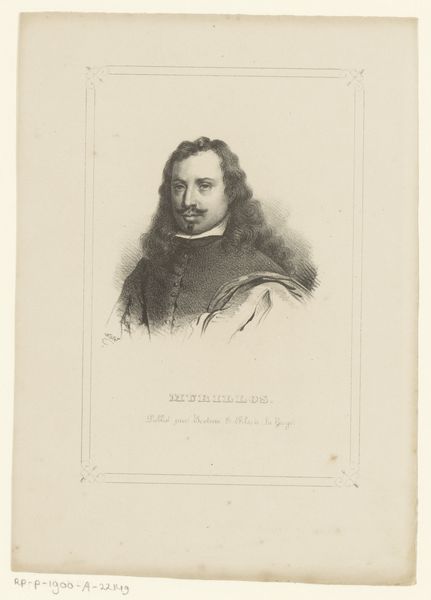

Portret van de Rotterdamse predikant Johannes Jacobus van Oosterzee 1834 - 1891

0:00

0:00

edouardtaurel

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

realism

Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 142 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is a portrait drawing of Johannes Jacobus van Oosterzee by Edouard Taurel, made sometime between 1834 and 1891. It's a pencil drawing and the detail is incredible, especially in the shading of his coat. What strikes me is the way the artist captured his seriousness. What do you see when you look at this piece? Curator: Well, the use of pencil immediately directs my attention to the means of production. The accessibility of the pencil, even in the 19th century, implies a certain level of democratization in portraiture. Was this a commission strictly for the elite, or were more modest portraits like this accessible to the rising middle class due to cheaper materials? Also, consider the social context: the sitter, a Rotterdam minister. How did the rise of religious movements and institutions create a demand for these kinds of images? Editor: That's a perspective I hadn't considered! I was focused on the subject, but the shift to the materials and their accessibility makes me rethink the intent and audience. Did the medium itself influence how people viewed portraiture at the time? Curator: Precisely. Pencil drawings, while capable of great detail, inherently possess a different status compared to oil paintings. What does that difference signify in the context of class, status, and the changing dynamics of 19th-century society? Was pencil drawing viewed as a more honest representation of the sitter? What does its creation involve materially? Editor: This makes me wonder about the labour involved in creating this drawing compared to, say, a painted portrait. It’s certainly given me a richer appreciation for the portrait. Curator: Indeed, by examining the material reality of its production, we begin to unravel a more complex story about the art and its place within its social and economic framework. It pushes us to challenge what constitutes 'high art' and 'low craft'. Editor: Absolutely. I'll never look at a simple portrait the same way again! Thanks for broadening my understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.