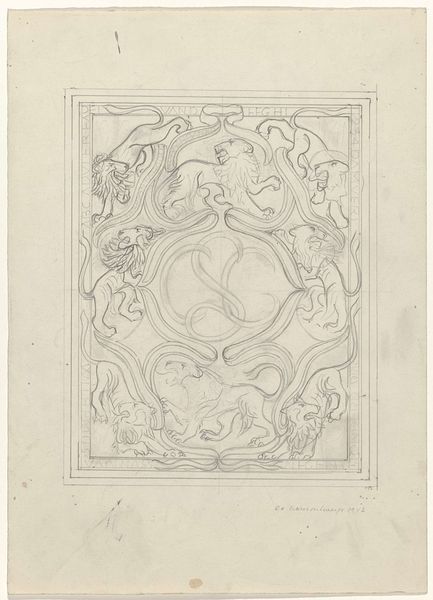

drawing, ornament, paper, ink, indian-ink, pen, architecture

#

drawing

#

ornament

#

toned paper

#

16_19th-century

#

medieval

#

hand drawn type

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

indian-ink

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

sketchbook art

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

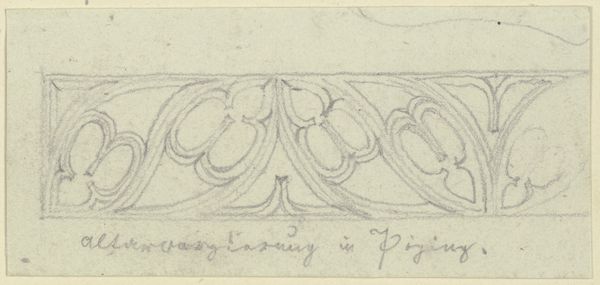

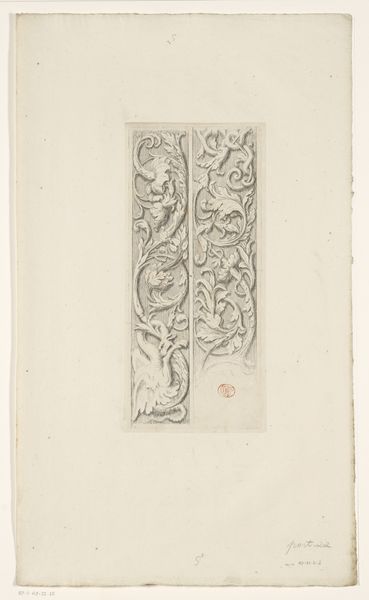

Curator: This delicate drawing in ink on toned paper is called "Freskierte Dacheinfassung von Sankt Nikola in Landshut" and it's by Karl Ballenberger. It’s currently residing here in the Städel Museum. The drawing presents an ornamented, medieval architectural feature, offering insight into 19th-century craftsmanship. Editor: There’s an austere, almost haunting quality to the sketch. I mean, the lines are crisp but the overall tone of the aged paper softens everything, gives it an antique affect that seems deliberate. A fragment frozen in time and paper. Curator: Absolutely, that’s a great starting point to delve into its historical meaning. As a study for a fresco in St. Nikola, this piece is intrinsically connected to religious expression and spatial politics of the time. We need to explore the ways sacred spaces, and by extension, the architecture, were gendered or racially determined. Editor: Indeed. It’s key to acknowledge the materiality here – the pen, the ink, the paper. This wasn’t about individual genius in some detached realm; rather, this sketch served a concrete, functional purpose within a workshop. And this use of pen, indian ink, and paper connects architecture directly to craft work! How fascinating that the sketch may exist more like a personal study inside his sketchbook. Curator: I think it invites crucial inquiries into labor history! Frescoes required not just the initial sketch, but a collective of artisans. What were their social standings? Who had access to this artistic creation? Was skill also somehow associated with gender? These are some relevant questions that deserve analysis. Editor: Definitely, because consider what kind of physical labor created this building! This is also very relevant within architectural historical analysis because it invites questions: was this drawing based on site research? How did Ballenberger construct this as a drawing? I imagine the repetitive nature of creating and reproducing this pattern demanded endurance. This informs our understanding of ornamentation more generally as material labor within cultural context. Curator: Agreed. Analyzing this intersection allows us to unearth so much more about 19th-century social stratification and creative industry, and perhaps draw connections to the politics surrounding preservation, ownership, and artistic authority in architecture. Editor: So this drawing, as humble as it looks, embodies layers of both intellectual design and material implications. It reminds me how labor intersects artistic creation in complex ways, especially within a religious space. Curator: And from that perspective, even a sketch serves as an important, yet also humble document for architectural, social, and art history, providing insights into spaces and systems.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.