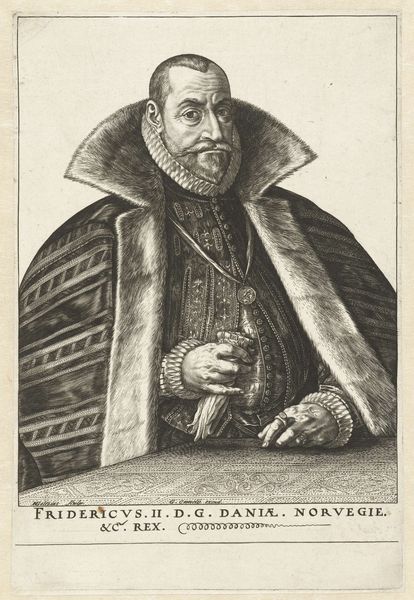

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

mannerism

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: block: 20.7 x 15.1 cm (8 1/8 x 5 15/16 in.) sheet: 29.5 x 17.6 cm (11 5/8 x 6 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Ah, here we have "Augustus Hertzog zu Sachsen," an engraving made in 1564 by Jakob Lucius the Elder. A powerful portrait, isn't it? Editor: Powerful, yes, but initially, a bit… severe? The stark lines, the formal pose. It feels like a statement more than a revelation. It reminds me of woodcuts but with extra finesse. Curator: That severity, I think, reflects the historical context. This is a portrait of Augustus, Elector of Saxony, a key figure in the Holy Roman Empire during the Reformation. The image was likely commissioned to project an image of authority and piety, crucial for a ruler navigating religious and political turmoil. Editor: So, not exactly aiming for warmth, eh? I notice he's holding a small hand fan – quite delicate in contrast to everything else. Intentional irony perhaps? Curator: Perhaps. The fan is a subtle signifier of status. The details throughout are doing so much work—the intricate patterns on his robes, those family crests framing his head… they all broadcast lineage and power in a visual language accessible to the time. The inscription at the top is explicit as well. Editor: Right, visually laying claim. This must have circulated widely, establishing him not just politically but visually. So it is essentially sixteenth-century branding! You've changed my first impression though - severe has shifted to shrewd. Curator: Precisely. Printmaking allowed for dissemination on a scale previously unimaginable, and rulers like Augustus quickly grasped the medium's potential. It speaks volumes about the growing role of visual imagery in consolidating power and shaping public perception during the Renaissance. Editor: And the craft itself – all those precise lines meticulously carved... It feels so solid, unyielding. What skill! I'm thinking now this engraving shows exactly what it had intended: power! Curator: Exactly! This piece prompts a wider look into art’s public function, and its ability to perpetuate societal structures. It seems as though, in some senses, art's primary functions remain today. Editor: Indeed. And that is why it makes the image ever the more resonant. Food for thought for when thinking about current pieces as well, or how portraits and pictures function now too. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.