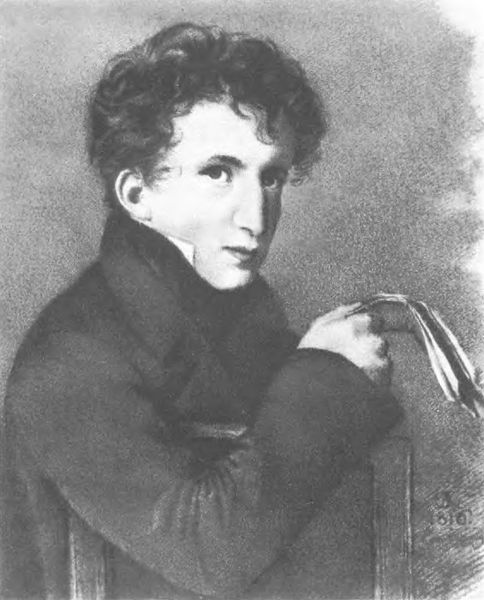

drawing, pencil

#

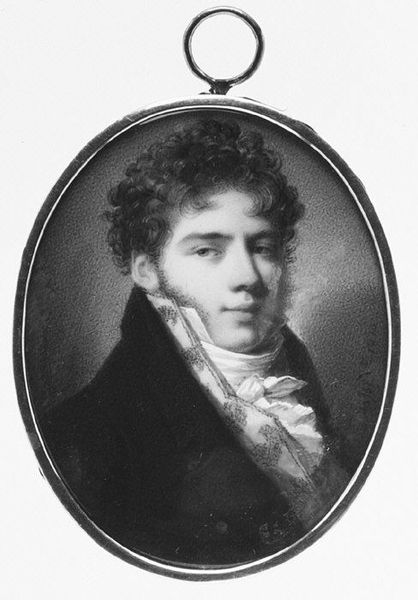

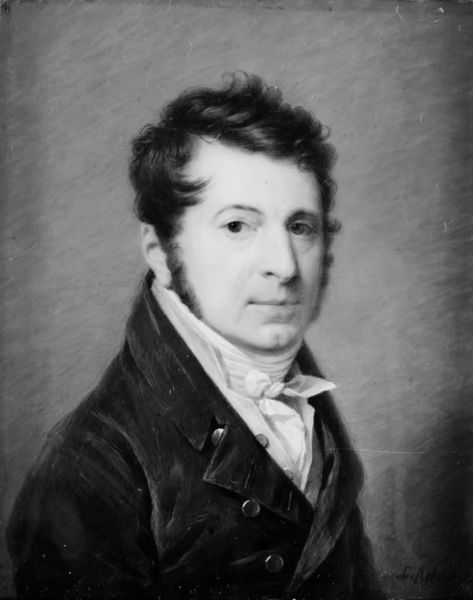

portrait

#

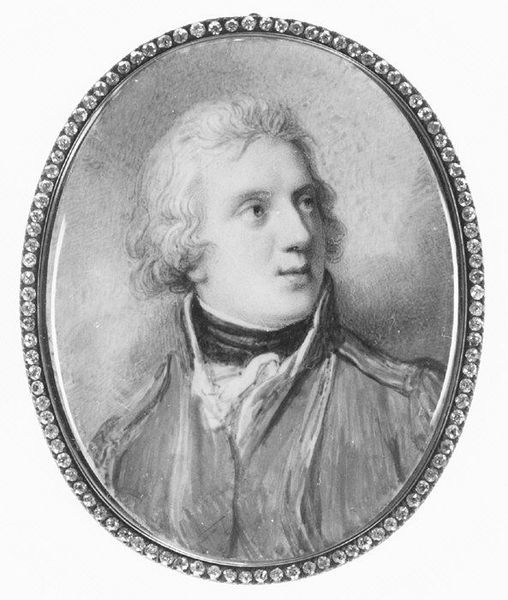

drawing

#

facial expression drawing

#

head

#

face

#

portrait image

#

portrait

#

male portrait

#

portrait reference

#

portrait head and shoulder

#

sketch

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

facial study

#

facial portrait

#

forehead

#

digital portrait

Copyright: Public domain

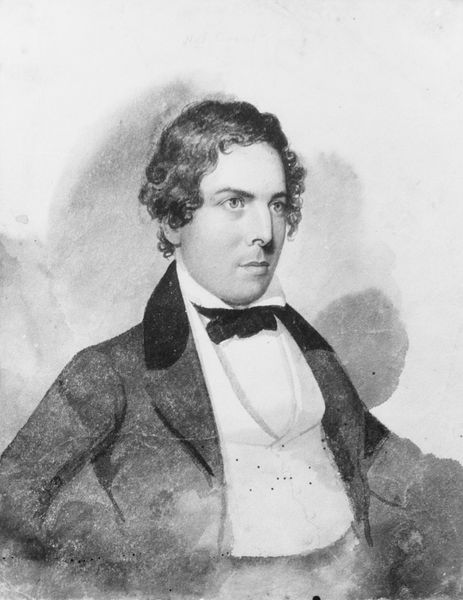

Curator: The gaze in this pencil drawing is piercing. What do you make of this rendering? Editor: It strikes me as possessing a quiet dignity, almost melancholy, the delicate pencil work softening what might otherwise be an imposing presence. Curator: This drawing, simply titled "Portrait of a Man," comes to us from the hand of Orest Kiprensky. It is housed in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, a testament to the artist's enduring influence. Editor: Thinking about those pencil strokes, I can almost feel the artist's hand moving across the paper. Was Kiprensky known for rapid portraiture? One can almost picture this work emerging from an intense sitting with the model. What would this drawing have been made for, who might he be? Curator: It is fascinating how a single portrait can generate so much speculation about labor, artistry, and meaning. Pencil portraits served a range of functions during that period. Sometimes it was as preparatory sketches, to record someone's likeness as swiftly as possible, like a photo taken on paper for possible future projects, while at others a work of its own in its production, where a single object would serve as a way for upper classes to consume art. Editor: It's interesting you mention consumption, especially in a society grappling with shifting class dynamics. Did Kiprensky use specific symbols to indicate status in his portraits? Is there a semiotics of the shoulder ruffle? A material stand-in for status? Curator: The symbols may be simple in this drawing, however, by examining Kiprensky’s access to materials, and even the texture of paper as it captures pencil marks in different tonalities reveals its own social-historical situation regarding labour and consumption. In any case, I still think his drawings speak eloquently of the individual spirit and Romanticist values through facial expression. Editor: Absolutely. And that speaks volumes about how the Romantic period reimagined what a portrait could represent, in a way it speaks through symbols but not so literally that can fully reveal everything, but through implications. It makes me think about how symbols take on new lives, reinterpreted across different hands that may never fully touch but feel each other. Curator: A fitting way to consider art: tangible encounters connecting us across different realities of labor.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.