Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

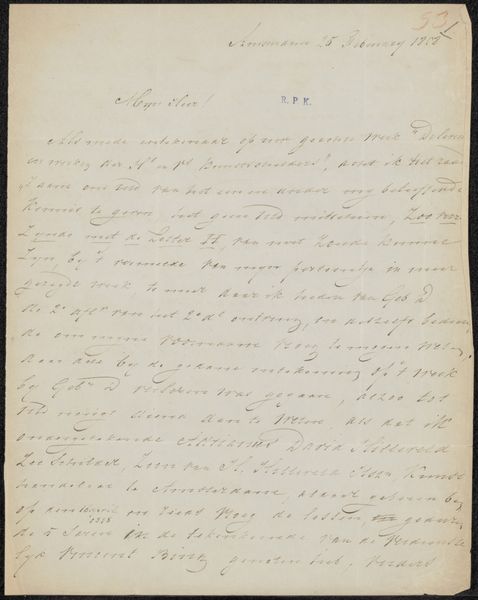

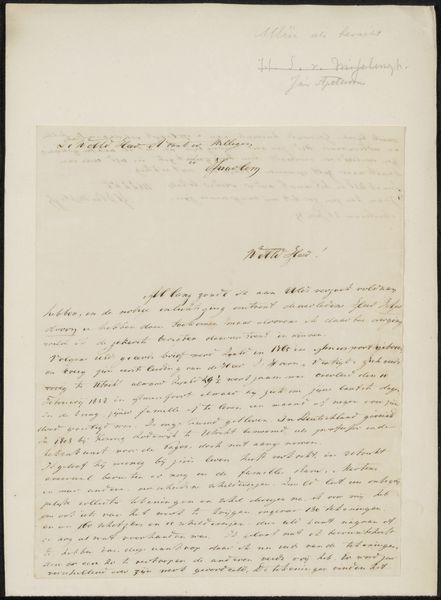

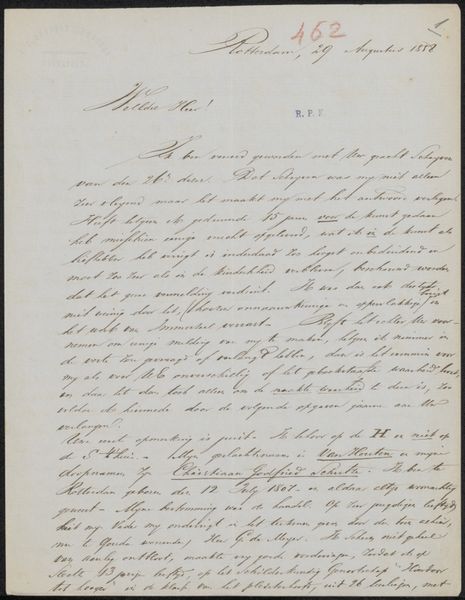

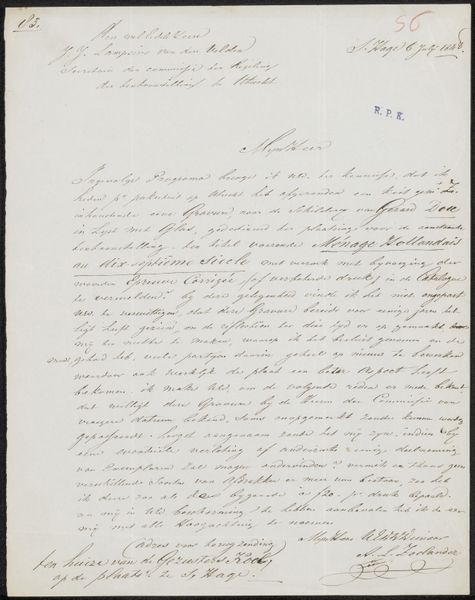

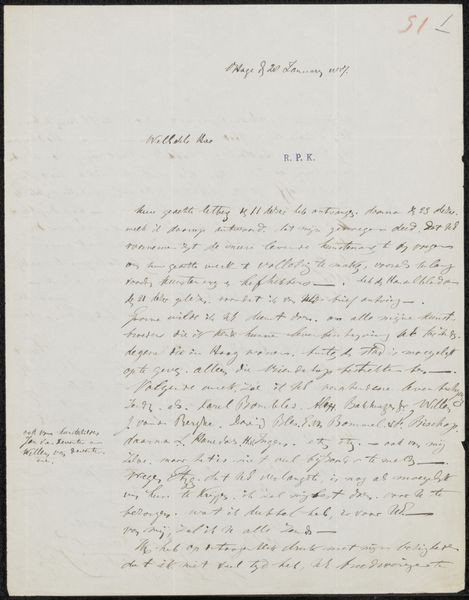

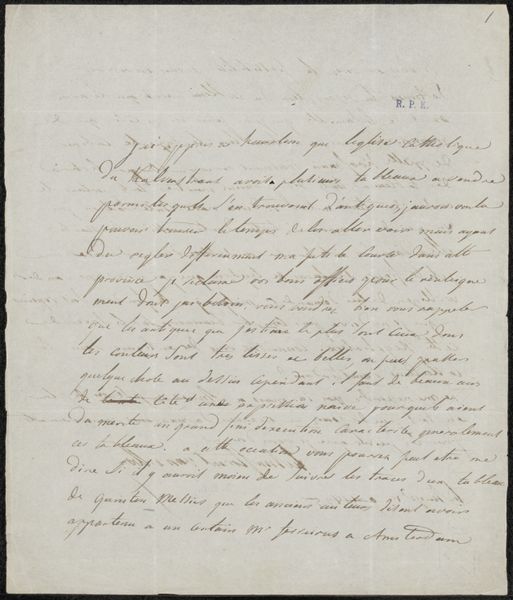

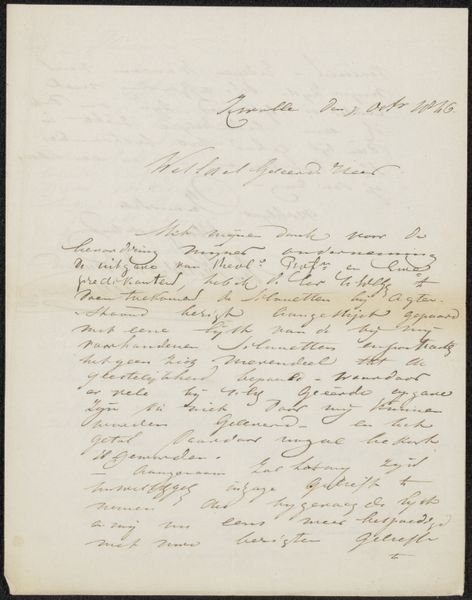

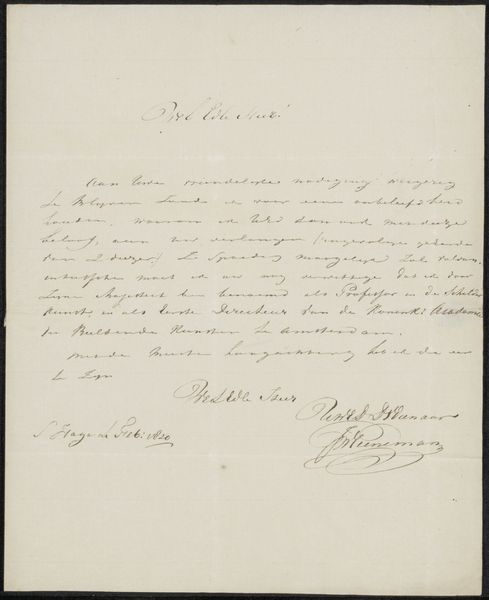

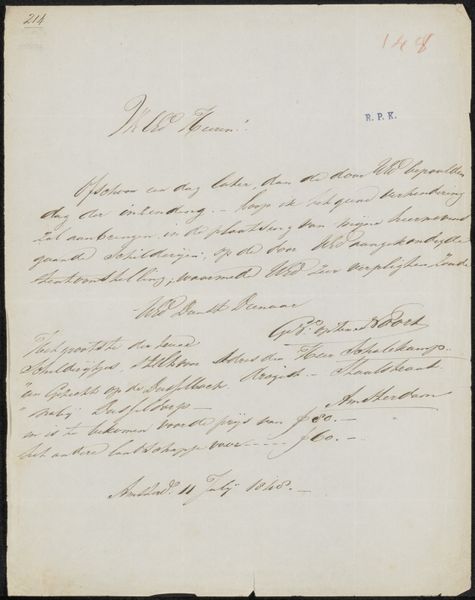

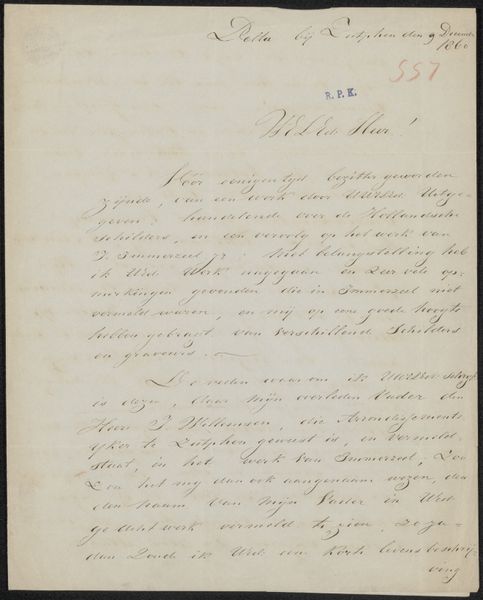

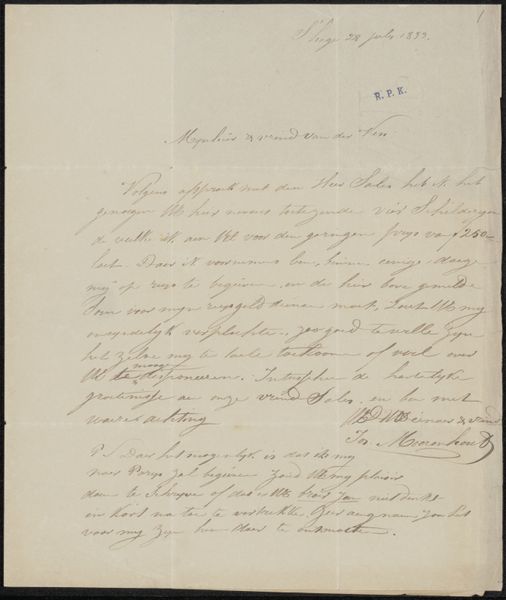

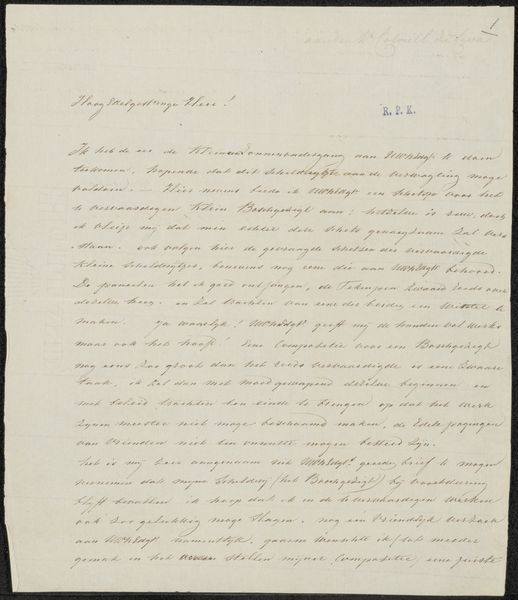

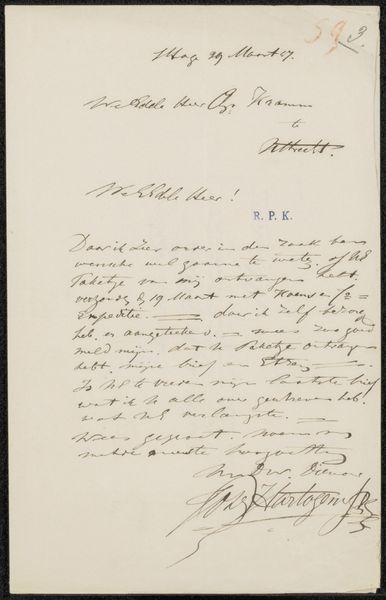

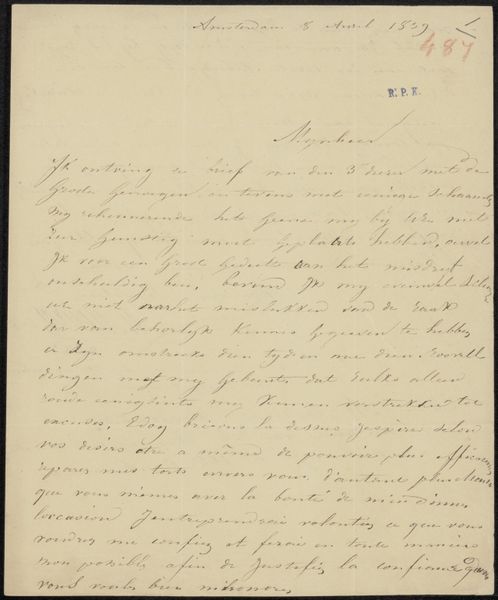

Curator: Welcome to the Rijksmuseum. Today, we’re looking at “Brief aan J.D. Dreijer,” or “Letter to J.D. Dreijer,” created possibly in 1857 by Petrus Johannes Schotel. This piece uses ink on paper and aligns with the Romanticism style. Editor: My initial reaction is one of intimacy. The cursive script and the paper's aging hue create a powerful sense of personal communication from a distant era, a moment captured in amber. Curator: Indeed. The composition of the handwriting across the aged paper creates a series of diagonal lines offset by the linear, blocklike quality of the header text. It shows us the intrinsic tension of a piece whose content has aged beyond its original function to take on more aesthetic form. Editor: Absolutely, and Schotel likely composed this not just as a note, but also considering how its content might play in a larger art-market ecosystem. This letter itself reveals concerns over a previous piece—all of which positions it beyond a private matter, hinting at broader cultural considerations of artist-client relations. Curator: Looking at the texture and contrast within the piece, one could surmise that the light areas suggest wear—these negative spaces highlighting the presence and absence implicit to ephemera like personal correspondence. Editor: These aren’t empty gestures, though; that Romanticism tag connects here as Schotel—already an established maritime painter— navigates the currents of the art market by corresponding in prose which, while perhaps purely functional, suggests emotional investments behind sales of seascapes or other nautical subject matter he created during the era. Curator: It is a study of balance between precision of message and emotional tenor and decay from the passage of time; even on paper, there's a palpable interplay here worth appreciating irrespective of content. Editor: A good reminder that documents, no less than paintings or sculptures, serve as material witnesses to their era’s economics and sentiments. By appreciating these details—along with all their encoded context and embedded anxieties about markets —Schotel comes back to vivid, present life before our very eyes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.