oil-paint

#

portrait

#

cubism

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

geometric

#

modernism

Copyright: Public domain US

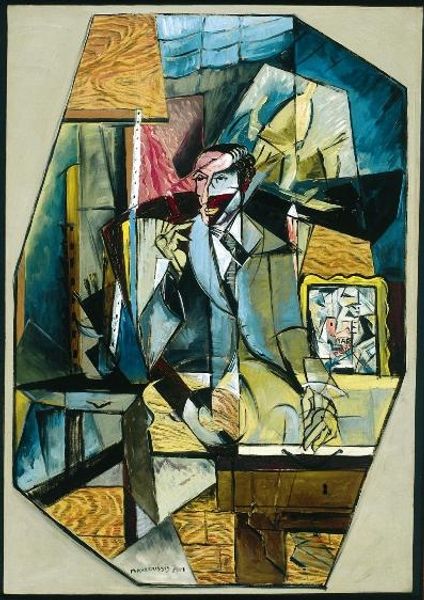

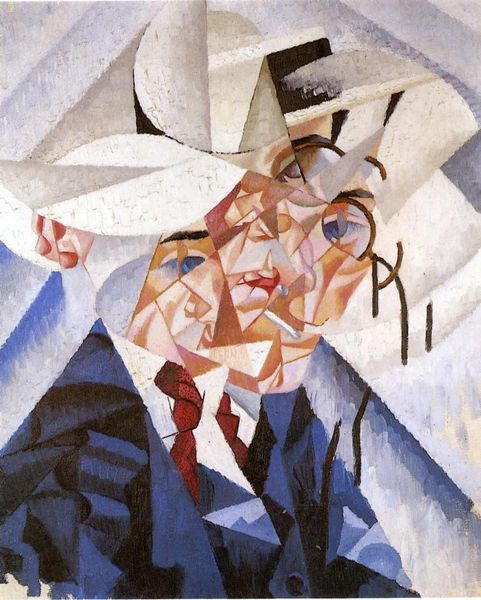

Curator: At first glance, Metzinger's "Portrait of Albert Gleizes" from 1912 overwhelms me with its deconstructed planes. What is your initial impression? Editor: I'm struck by the material density, all those planes and edges layered with visible brushstrokes. You can almost feel the thickness of the oil paint. What’s he trying to do, take the very stuff of painting and turn it into a representation of… another painter? Curator: Indeed! This work, an oil painting from the height of Cubism, presents Gleizes, also a painter, as a series of fractured forms. It is about the multiple perspectives contained in a single view, influenced by developments in scientific understanding of time and space. Editor: So it's not about faithful representation, but more like an accumulation of impressions…I see how the dark colors—grays, blacks, browns—give the figure a sculptural quality, like a monument almost. Was there an ambition here to solidify the status of the artist? Curator: That’s a perceptive point. In this Cubist framework, elements carry weight symbolically. The hat, the suit, rendered in such somber tones, speaks to the societal role, the intellectual seriousness these artists were claiming for themselves. The monochrome palette is almost devotional in its restraint. Editor: And yet, it's a manufactured solemnity, isn’t it? The visible labour, all those calculated brushstrokes, betray the artificiality of it all. One feels the process as much as the final image. There’s almost a tension there—between the desire to ennoble, and the actual physicality of creating an image. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the fracturing not just as a stylistic choice but as a means of dismantling traditional portraiture's focus on surface and presenting a multifaceted internal state. He wasn't painting Gleizes the person; he was conveying something essential about his intellect and position within a new cultural movement. Editor: Looking closer, there's such deliberate awkwardness. This dismantling of form feels deeply material—a forceful arrangement and rearrangement of paint into recognizable shape. In some sense, it suggests the violent break of Modernism away from established modes. Curator: Precisely. Looking at the figure and geometry in unison allows me to understand the revolutionary spirit not just visually but intellectually. The painting then isn't merely a portrait, but a manifesto. Editor: A potent demonstration, wouldn’t you say, of how artistic vision is shaped by its own production, and in turn, shapes the cultural landscape it occupies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.