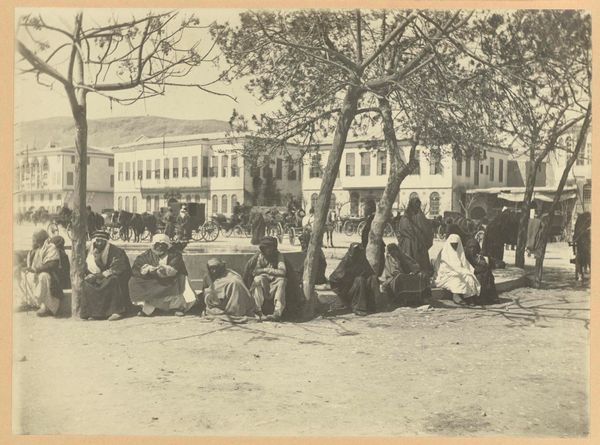

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 111 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Today we’re looking at a photograph entitled "In den tuin van het hospitaal" or "In the Hospital Garden", taken sometime between 1903 and 1910 by Hendrik Doijer. Editor: My first thought is how carefully staged it seems, almost a posed scene of labor. There's a certain quiet dignity despite what I imagine to be arduous work. Curator: It’s interesting you say "staged." Given the gelatin-silver print medium, there's certainly a production element at play. Think about the accessibility of photography then, who was controlling the means of image production and whose stories they chose to tell, particularly around labor, class, and social spaces. Editor: Right, and how those stories get constructed! The composition and light here almost sanctify this garden work. Note how their white head coverings and placement evoke biblical scenes of communal tasks. What might Doijer be suggesting about their roles within the hospital’s world? Are they healing the soil just as the hospital tends to the body? Curator: The act of care is palpable. Are we, through the photograph, asked to reflect on the invisible labor required to create these restorative environments, the economics intertwined with those gardens, hospitals, and race? Editor: Exactly. The symbolism feels multivalent. The garden itself—paradise tamed and cultivated. The clothing -signifying faith and yet a certain uniformity. These women become figures in a landscape of care and perhaps also quiet subjugation. The act of physically altering nature mirrors the societal pressures placed upon them. Curator: This reading beautifully connects the garden and figures. It is essential to acknowledge the complex historical context of this seemingly peaceful image; who benefits and what relations are being displayed? What kind of dialogue can emerge about social structure through photographic means of representation? Editor: Understanding art is never truly solitary. It lives through the conversations it starts, and hopefully this photograph opens doors to even deeper reflection about how imagery and symbolism contribute to these dialogues about societal structure, and cultural meanings through time. Curator: Agreed, a necessary intersection between the processes of representation and the loaded iconographies found throughout the visual world and its history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.