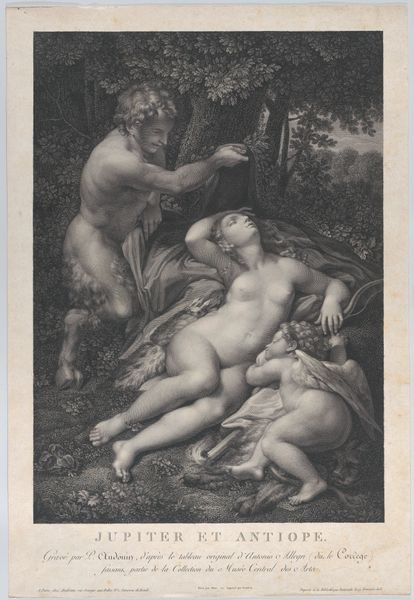

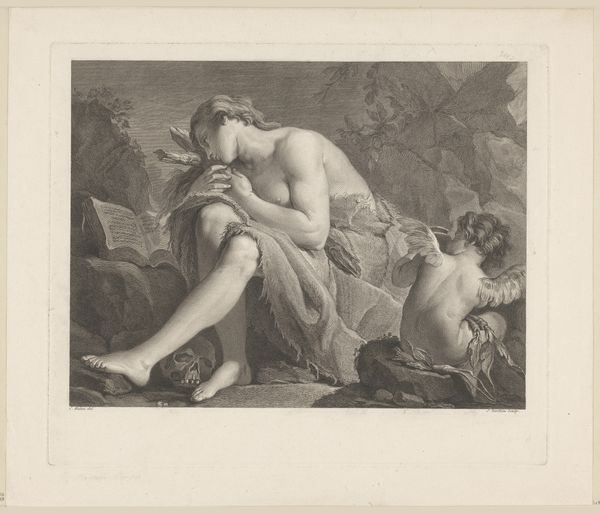

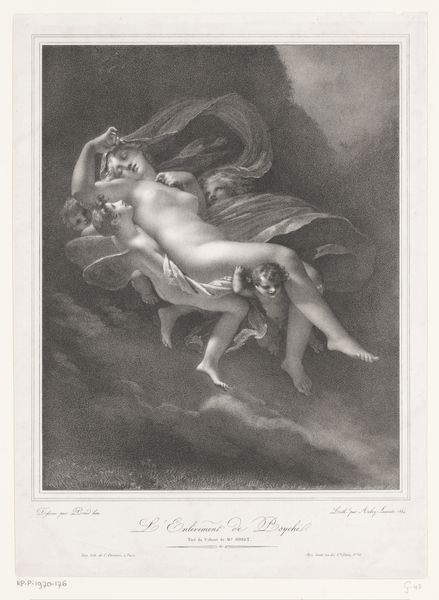

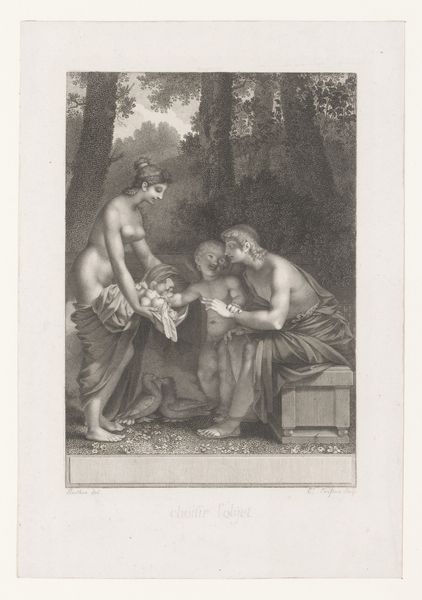

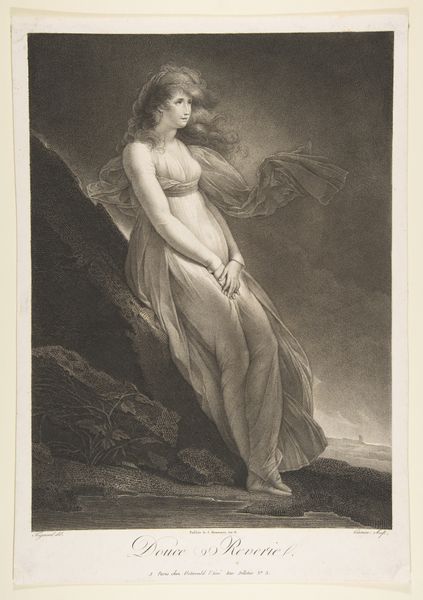

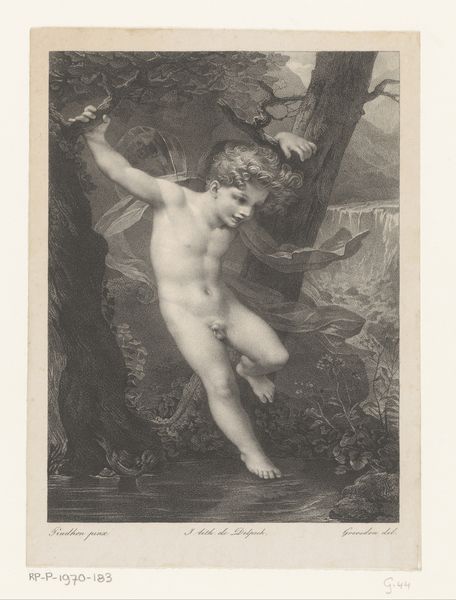

drawing, engraving

#

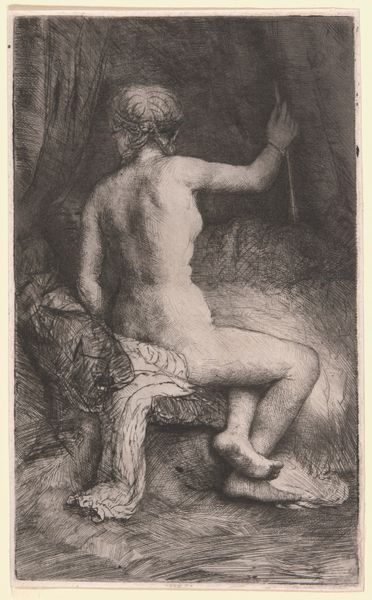

drawing

#

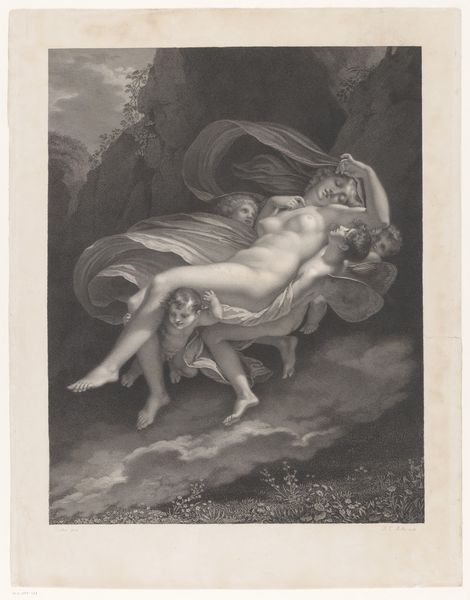

allegory

#

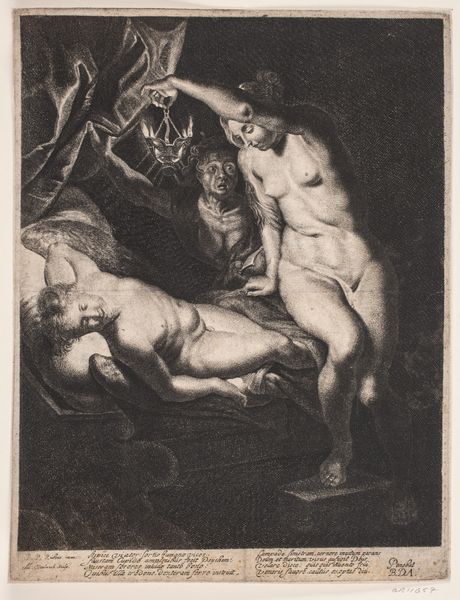

baroque

#

charcoal drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

nude

#

engraving

#

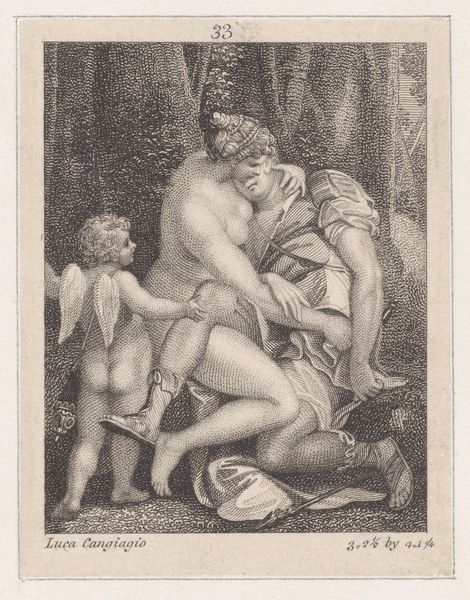

erotic-art

Dimensions: height 358 mm, width 254 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Jupiter en Io", an engraving made between 1529 and 1743, currently at the Rijksmuseum. The nude figure and the dark tones give it an almost dreamlike quality, and it looks like some charcoal or maybe chalk was used to give definition. How do you interpret this work, focusing on its materials and methods? Curator: Look closely at the process of engraving itself. It is not merely a reproductive technique, but a means of production that imposes a specific visual language. Think about the labor involved—the careful etching, the inking, the printing. The eroticism is, in some ways, manufactured by the very act of reproduction for a consumer base. Do you consider this 'art' or another form of manufacturing? Editor: I see what you mean about the manufacturing process imposing its own character. It’s interesting how the theme of eroticism, even back then, could be tied to consumerism and mass production. What do you think the choice of engraving as a medium says about its accessibility, given paintings would only be seen by a few? Curator: Precisely. Engraving made such images widely accessible, turning "high art" subjects into commodities. Consider the societal impact of distributing previously exclusive content – transforming artistic expression into items for the masses. Think about the power dynamics: whose labor produced this, for whose consumption, and to what end? How might those relations be contributing to it now? Editor: It definitely gives me a new perspective. Focusing on the engraving process really opens up a discussion about the art market itself and who controlled it, especially concerning accessibility to broader audiences through printed copies. It certainly shifts my initial view. Curator: Indeed. Examining the materiality of the piece prompts us to consider it as more than just a static artwork but a cultural product embedded in historical labor practices and consumption patterns.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.