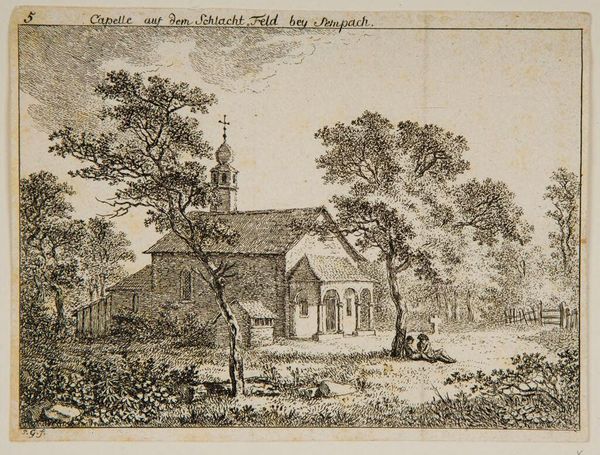

print, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: So, this engraving offers us a glimpse of the St. Agnes Convent in Utrecht. Abraham Rademaker created this artwork sometime between 1727 and 1733, though the scene depicts the year 1670, a bit of temporal playfulness on Rademaker's part, wouldn't you agree? Editor: It certainly feels…deliberate. It strikes me as melancholic. All those careful lines feel like an attempt to preserve a memory, perhaps even an ideal. The scene almost fades into memory as we move toward the edge. Curator: Rademaker was known for his landscapes and cityscapes, often imbuing them with historical or topographical significance. Note the careful rendering of the architectural details—the gables, the windows, and even the textures of the brickwork. He's playing with light and shadow to give the structure depth. The formal, geometric garden is interesting, too, no? Editor: Indeed. And notice how the horizontality of the building and the implied grid of the garden are offset by the sharp vertical thrust of the church spire. It introduces an element of dynamism and perhaps even a subtle commentary on earthly versus divine space. But more profoundly I wonder about this lonely figure in the bottom left - so disconnected and apart. What do you suppose that's about? Curator: Ah, the human element. These aren't just sterile architectural studies, are they? It’s a narrative, a staged moment of everyday life against the backdrop of this institution. The pair in conversation, the figure reclined—they're not simply filling space. They are active, purposeful participants in Rademaker’s broader composition. Editor: I’d love to imagine what's going on in their heads; whether they felt peaceful or alienated in contrast to the geometric formality. If I sat there, I think, in front of those cold brick structures I may also find a similar somber and distant pose as that figure on the lower left of the print. Curator: That interplay—between the built environment and our place within it—becomes the subject. Through lines and shadows, Rademaker allows the mind to engage, even in these humble quotidian scenes, the potential and poignancy of our connections. Editor: Well, that’s helped me find some harmony in this picture—not as somber but instead gently thought provoking in relation to place, time, and one’s own physical form. Thanks for pulling me from my dark inclinations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.