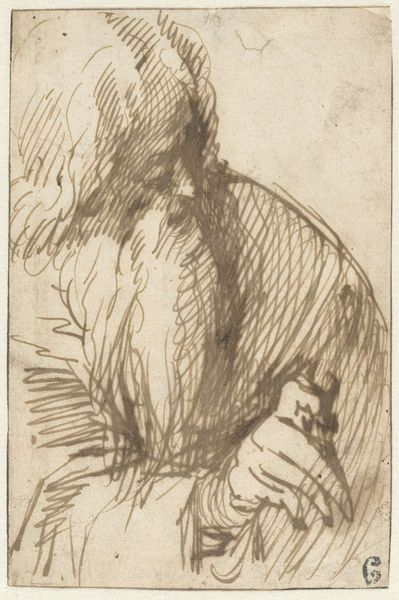

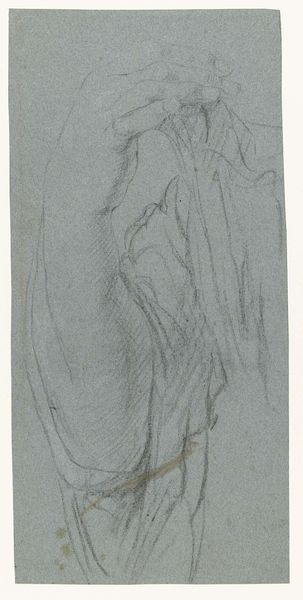

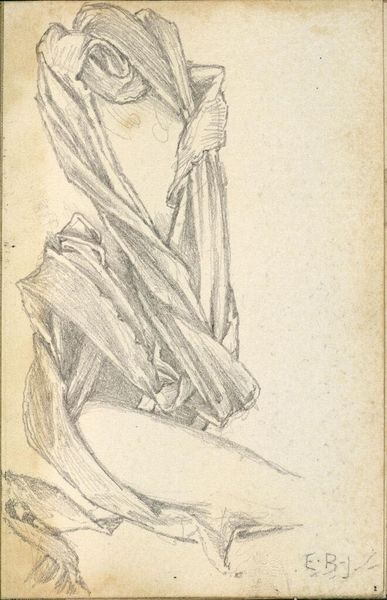

drawing, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

impressionism

#

pencil drawing

#

graphite

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

Curator: It's almost dreamlike, isn't it? Whistler's "A Child on a Couch, No. 1" made between 1873 and 1875, simply shimmers with a fragile beauty. It is a graphite pencil drawing. Editor: My first thought looking at it is 'process.' I see labor and intent, cross hatching as a sign of commitment and the layering of strokes revealing an engagement with material – the build up, the softening of line. The child almost fades in and out. Curator: Exactly! It’s more of a feeling, an impression—it could almost be a memory dissolving, like trying to grasp smoke. He's distilled the essence of childhood, that liminal space between waking and dreaming. Think how the Impressionists treated the light, a study on ethereality, capturing moments fleeting from vision. Editor: While that poetic analysis rings true, I also find myself considering the graphite itself. How was it sourced? What was the socio-economic context of its production? We rarely think about where these art materials originate, the labour that goes into prepping the material before Whistler himself put pencil to paper. Curator: An interesting counterpoint. He may not have had his own factory to grind the graphite, but perhaps we can see how Whistler transforms this modest medium? This is hardly documentation, no precision; it’s like he is whispering secrets onto the paper. And as for social context, it reminds me of all of the Victorian portraits which depicted women on couches: they always represented women that were either ill, fatigued, or waiting. I wonder if that's part of his intention here? Editor: Well, it would not have just been Whistler's "whispered secret," but it would be equally revealing to understand the commercial production methods and networks to fully credit those unseen laborers too. I wonder, for instance, about the paper, if it was from linen or wood pulp – both were increasingly common, and one or the other determined the survival of marks over time... Curator: Absolutely vital considerations. Thank you for pulling us down to earth! So we are then caught between, materiality, social context, a dance, but ultimately he presents us with an echo of something tender, perhaps lost. Editor: Yes. An echo made visible through labour, a document to lost labour if nothing else.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.