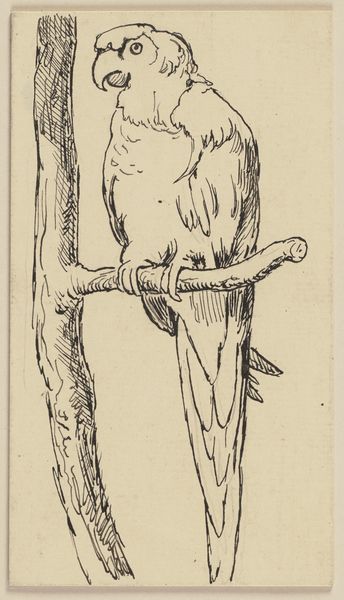

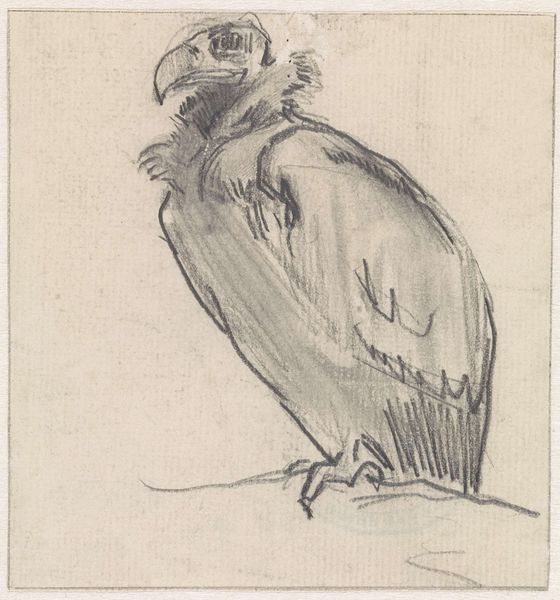

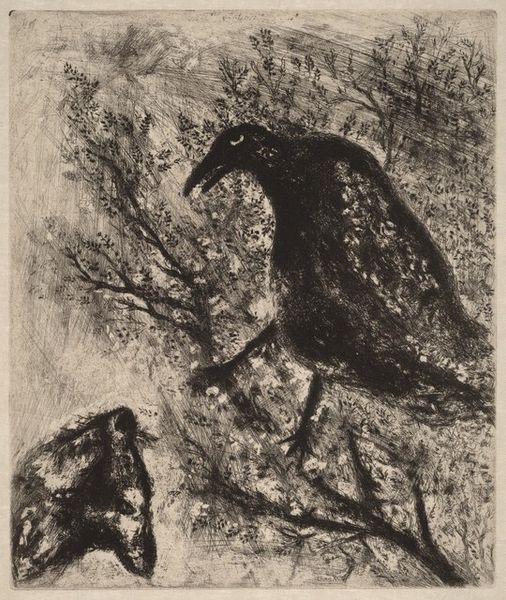

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

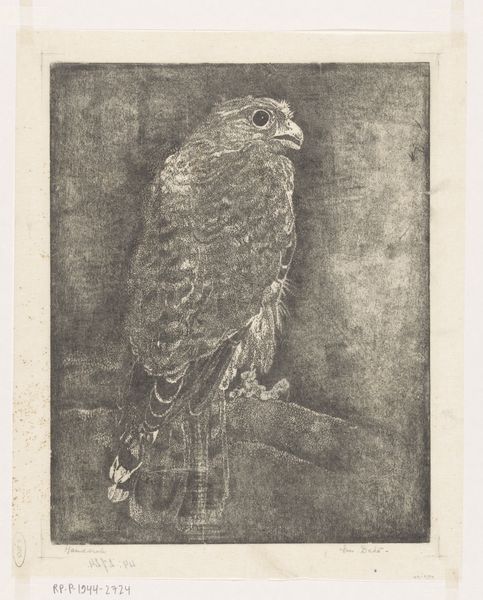

Dimensions: height 138 mm, width 86 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This print, "Papegaai op een tak," or "Parrot on a Branch," by Willem Adrianus Grondhout, dates from between 1888 and 1934. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It strikes me as melancholic, even lonely. The parrot's posture, the muted tones, all contribute to this feeling of quiet isolation. I wonder, formally speaking, how the artist achieved this effect. Curator: The material choices are key. Grondhout uses etching, ink, and possibly pencil on toned paper. These mediums lend themselves to creating subtle tonal gradations. Note the lines; it's almost like he's capturing a fleeting observation from a sketchbook. He's not creating a polished presentation piece, it’s quite raw, closer to amateur sketch art. What labor and social contexts do you see informing the work? Editor: Well, look at how the varied and delicate strokes of etching define the form. The composition, with the parrot taking up most of the vertical space, contributes to that effect you mentioned. Semiotically, we associate birds with freedom, and here, that potential freedom feels restrained, doesn't it? There's a philosophical suggestion of confinement. Curator: I see your point about confinement. It's interesting to consider this image in relation to the increasing urbanization in the Netherlands at the time, with nature being something commodified. A parrot might have been seen as a luxury, a symbol of status. In that sense, it's a commodity that exists separately from any natural ecology. The process behind reproducing images through prints makes one wonder if he considered reproducibility, given how amateurish some would classify the rendering here. Editor: That reading gives another layer. The roughness of the hatching also lends a tangible, tactile quality. It doesn't seek perfect imitation, does it? It strives for essence through pure structural means. So, from this encounter with materials and craft, there rises some understanding of the philosophical concepts involved! Curator: Yes, indeed. Considering it a social symbol embedded in economic practices brings to light an additional perspective on that isolation that we noticed initially. It all reflects cultural circumstances during that era, how production intersects with aesthetics and consumerism. Editor: For me, the work resonates in that formal tension of texture, shape and semiotics—with its limited range somehow saying everything at once!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.