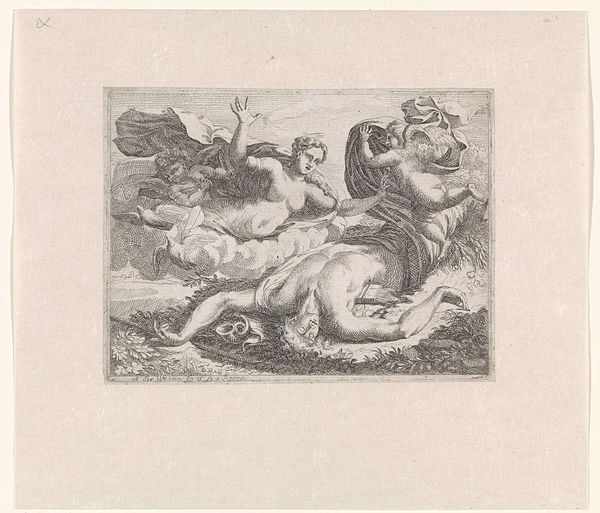

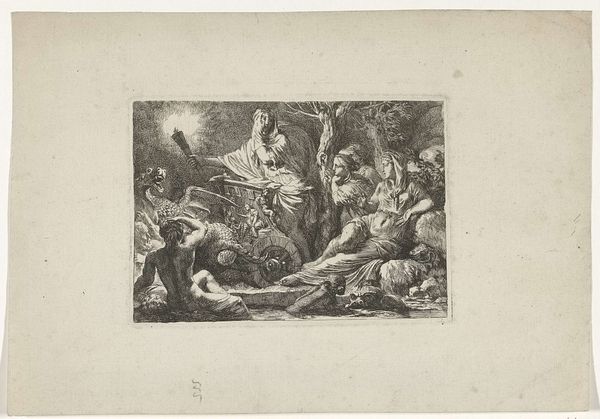

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

#

toned paper

#

quirky sketch

#

baroque

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 113 mm, width 144 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Before us, we have "Goats and Calabash," a print realized sometime between 1611 and 1661 by an anonymous artist. What strikes you initially? Editor: Well, it feels almost claustrophobic despite being a pastoral scene. The density of the foliage contrasted with the emptiness of the sky makes me wonder about the hidden labor that shaped this cultivated space. Curator: I see your point about the claustrophobia. I'm more interested in how the drawing plays with established societal norms surrounding agriculture and landscape depictions, perhaps offering subtle social commentary. Notice the calabash; is it simply part of the background or symbolic of abundance and nature's provision? How does the gendering and aging of the goatherd inform labor practices of this era? Editor: Precisely. This isn’t just some idyllic depiction of country life; it reflects the material conditions under which people interacted with animals. The etching suggests an almost symbiotic reliance of the shepherd and herd for subsistence. Considering it's a print, its reproducibility complicates the singular 'artistic vision.' Think about the access to paper, ink, and the dissemination process; that determines who could own or view such imagery. Curator: I appreciate your emphasis on reproducibility. I would add that we have to examine the broader context in which these images circulated. Were they intended for elite patrons, perhaps subtly critiquing their exploitation of rural labor, or were they for a broader public with more explicit messaging about stewardship? Editor: Looking closer at the drawing, it is the etching process itself that is noteworthy; the way the artist varies the line weight, to render light and texture is masterfully executed. We should really investigate the materials, the composition of the ink, and the production dynamics. Did the artist prepare the paper or delegate to the workshop? Curator: Indeed. Considering it comes to us from the Rijksmuseum, we must also reflect on how the work ended up in a national collection—how historical narratives and power dynamics have influenced which stories we value and preserve. The absence of the artist’s name is striking too. Editor: True, authorship certainly complicates issues of attribution and labor value, doesn’t it? Overall, examining art through its materiality and process encourages us to think beyond conventional art history. Curator: And by engaging art from a socially conscious point of view, we not only understand the piece better but can reveal critical perspectives regarding inequality, social justice and lived experience. Editor: Right, this intersection of labor, landscape and social status provides critical layers for appreciation of historical context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.