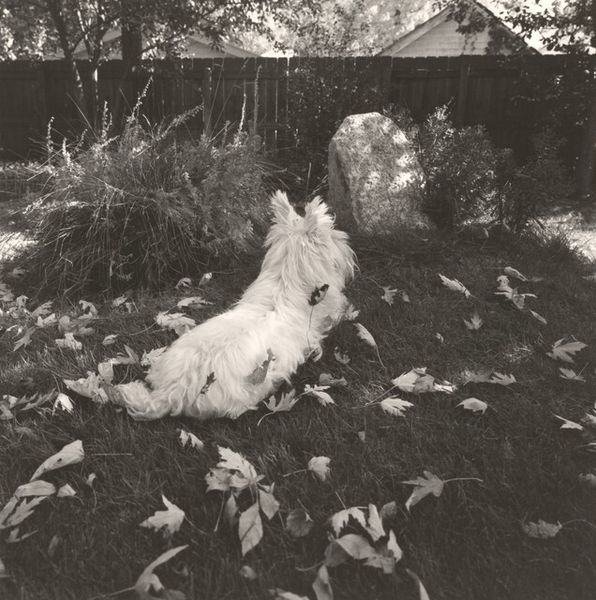

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

black and white

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome

#

realism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: image: 19.7 × 13.1 cm (7 3/4 × 5 3/16 in.) sheet: 35.3 × 27.6 cm (13 7/8 × 10 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: What strikes me first about this photograph is the light, filtering so beautifully even through the dense foliage, creating almost dreamlike gradations. Editor: Absolutely, there’s a distinct atmosphere there, a certain softness to it all. We are looking at "Longmont, Colorado, Sally in the Backyard," a gelatin-silver print captured sometime between 1982 and 1992 by Robert Adams. Adams, of course, is so well-known for chronicling the changing landscape of the American West. Curator: "Sally in the Backyard," what a title. I imagine it's Sally, the shaggy dog towards the back of the picture, gazing pensively into the depths of the frame. Is it my imagination or is the garden sort of an "allegory" of human life itself, perhaps? Look, at first glance it all looks very wild, and a bit gloomy—yet it feels nurtured, protected somehow by that strange wire fence or decorative screen… almost tender, wouldn’t you say? Editor: Yes, tender is one word, another could be fraught. That image of supposed domesticity and care that you see… I can’t help but wonder, who is it really “for?" The work comes from a pivotal period when Adams was deeply invested in ecological themes and how the expansion of suburbia intersected with both personal histories and the larger environmental narrative. That delicate metal border –is it safeguarding life or confining it? Adams consistently questioned the narratives of progress and beauty. Curator: Mmm. Good point. So even beauty itself is brought under suspicion? I am wondering, perhaps this very act of trying to define "beauty" can imprison it. Can any real kind of "progress" actually exist? Maybe progress and beauty are just another kind of artifice… Perhaps, like that fence. Maybe wildness is all we've actually got. Editor: Well, if Adams' images teach us anything, it’s to look closely at the everyday— at those spaces where nature and humanity negotiate— to confront difficult questions about how we choose to live. There are always paradoxes. The work resists easy answers. Curator: Maybe that’s its ultimate charm. Editor: And perhaps its deepest provocation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.